Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

PLAGUE ON OUR SHORES

Plague claimed more

lives than firePART I | II | III | IV | Epilogue

By Burl Burlingame

Star-BulletinTHE Great Chinatown Fire was, next to the Pearl Harbor attack, the greatest public-safety disaster in Hawaiian history. During the next several months, the city struggled with temporary housing and food for the refugees, and many stayed in relocation camps through the summer. Chinatown had been erased, and businessmen like Lorrin Thurston saw the event as sheer good luck, an opportunity to move "white" businesses into the area. The hard feelings and mistrust between the mostly Asian victims and the mostly white and Hawaiian authorities never completely went away.

The Chinese population in Hawaii never recovered. The numbers of Chinese continued to slip over the years, from 20 percent of Hawaii's population to less than 5 percent in the 1990 census.

The fire did manage to eradicate the Black Death contagion in the area. Although many continued to sicken and die from the disease over the months and years to come, the breeding grounds for rats and fleas in Chinatown vanished in the flames of 1900.

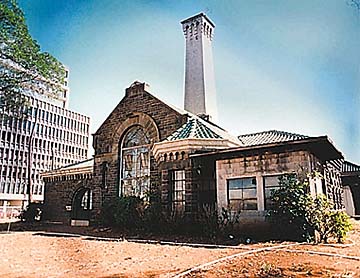

Honolulu authorities began a frenzy of sewer-building and other sanitation-oriented public works; the pump house on Ala Moana Boulevard is a monument to the lessons of Chinatown. Once considered a likely spot for a historical center, today it stands empty, windows shattered.

And although dozens died from plague, the great Chinatown fires -- including the one in 1886 that also leveled the area -- apparently claimed no lives.

An exact number of victims from the 1900 outbreak may never be known. Judging from newspaper reports, an astonishing number of citizens were simply dropping dead in the streets, but exhibited no classic signs of Black Death such as swollen lymph glands or skin-blackening. These cases were filed as "consumption" or "natural causes." However, the septicemic version of bubonic plague acts so quickly the victim often dies before symptoms can occur, and it's likely -- particularly in cases in which the victim was young and healthy -- that many, if not most, of these deaths were actually plague-related. And how do you classify the Chinese girl who accidentally fell and crushed her skull as she fled in fear of medical authorities?

According to a report published in the early 1930s, 337 people in Hawaii were known to have contracted bubonic plague. Of these, 34 survived, a mortality rate of 90 percent, which is high even for Black Death.

The last known human case of plague in the islands was in 1947 in Kamuela, the last known rodent to have it was captured in 1957, also in Kamuela. Vector-control authorities continue to routinely test for plague among Honolulu's waterfront rodent population because a new outbreak could occur at any time.

According to Norman Sato of the Health Department, the current population of rodents in Honolulu is the highest he's seen in 30 years. Plague struck in Surat, India, in 1994; in California in 1996 and in Nevada in 1997. It is endemic in the wild-rodent population of the Western United States, and since the fleas can live, hungry and plague-ridden, for weeks after the host dies, campers and hikers are urged to avoid sites where animals such as ground squirrels have suddenly died en masse.

According to the National Science Foundation's Long-Term Ecological Research center in New Mexico, bubonic plague is on the rise, as well as other rodent-borne pathogens such as hanta virus. In a November article in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, the center discusses a 60-percent rise in human plague vectors during wet winter months in the American southwest. Even with precautions, 10 to 15 humans in the United States come down with Black Death every year, and in Third-World areas like the Congo and Kazakhistan, it is epidemic.

Just a couple of months ago, health officials in Lancaster, Calif., were horrified to discover a five-month-old kitten adopted by residents of a trailer park had bubonic plague.

And in yet another irony, researchers at the Laboratory of Geonomic Diversity in Frederick, Md., discovered in 1998 that descendants of plague survivors have high resistance to AIDS. The primary clue was a genetic mutation that blossomed in Europe 700 years ago -- right after the Black Death cut a swath through the population, not only changing the structure of medieval society, but its evolutionary genetic makeup as well. The trigger "had to be an infectious disease, and one with a high mortality, like a bullet to the head," explained Dr. Stephen O'Brien of LGD.

We now know what the terrified citizens of 1900 did not, that the plague bacillus was transferred via blood, and we have what they did not, antibodies and serums that can stop the plague from contagion if caught early enough. The 20th century was the golden age of antibiotics, and it is hard to now imagine a bacteria-borne disease becoming pandemic the way plague did at the turn of the century or influenza did in 1918.

This comfort zone of modern medicine will surely change, and has already begun to do so. A bacillus is a living creature and subject to the same laws of evolution we all are. For years, infectious-disease experts have claimed antibiotics are used too generously, leading to the inevitable evolution of "superbugs." Like cockroaches that safely dine on bug poison, these bacteria have the ability to develop resistance that outruns our capability to invent and test new drugs. If that happens, medicine may return to he pre-antibiotic days of 1900. Once again, simple infections will kill.

Recently, for the fourth time in three years, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Ga., an American hospital patient has been infected by bacteria with partial resistance to antibiotic treatments of last resort. This victim was a 63-year-old woman who died of a simple staph infection that shrugged off the potent antibiotic vancomycin.

"This is a heads-up, alerting us that there may be a new problem on the horizon and warning us to take action," said Dr. Julie Gerberding, director of the CDC's Hospital Infections Program. Reducing antibiotic resistance is a crash priority these days within the CDC.

Black Death has not gone away. The Yersima pestis bacillus is still part of our global environment. Black Death is just biding its time, testing our wavering defenses, quietly mutating with infinite patience.

Click for online

calendars and events.