Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

PLAGUE ON OUR SHORES

Dark Days

Black Death crept into town,

setting Honolulu into panic

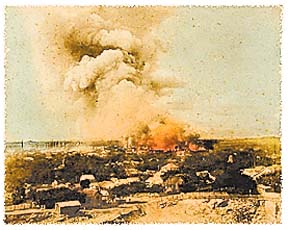

in January, 1900On New Year's Eve one hundred years ago, the first of a number of controlled fires were set in Chinatown as a way of defending Honolulu from bubonic plague, known in history as Black Death. Next to the Pearl Harbor attack, the outbreak of plague was the greatest public-safety disaster in Hawaiian history. The government was determined to do anything to save the city -- even burn it to the ground. Today we begin the first of a four-part series describing the events leading up to what became known as the Great Chinatown Fire. PART I | II | III | IV | Epilogue

By Burl Burlingame

Star-BulletinJUST over a century ago, on Oct. 20, 1899, the freighter America Maru tied up at the Pacific Mail wharf in downtown Honolulu and quickly unloaded a cargo of rice and other foodstuffs. The cargo sat on the pier for a couple of weeks before being moved.

During the first weeks of November, dock workers on the Pacific Mail pier noticed that rats were behaving strangely, venturing into the light, dying in apparent agony. Not just a few. Hundreds of rats littered the pier. Workers shrugged and swept the dead animals off into the harbor water. Good riddance.

At the same time, a 22-year-old Hawaiian woman named Malaoa Momona, who lived in a dilapidated building on the corner of Smith and Pauahi street, fell ill. Her regular doctor, H.W. Howard, was on Kauai, so Dr. S. Kobayashi was called in. When he arrived on the evening of Nov. 6, Kobayashi declared nothing could be done for her, and left.

Momona died during the night. Because he had not actually treated her, Kobayashi refused to issue a cause-of-death certificate. Howard also refused to issue a certificate. The city coroner had no choice but to classify the death as "unknown," and Momona might have been forgotten were it not for events that followed.In early December, the fragility of life was on the minds of citizens. The Queen's Hospital doubled its usual number of patients in November, so many it was forced to turn away a Hawaiian with tuberculosis. Also within the previous month, there had been three mysterious deaths among the normally robust Hawaiian crew aboard the inter-island steamship Claudine. And the census results for the turn of the century had just been made public, with some disturbing statistics.

The Hawaiian Star pored over the census and noted disease mortality had risen sharply in Honolulu. What was the cause? The only case listed as "unknown," however was Momona's, and the newspaper examined statements by both doctors. "In consequence of all this, the only positively known thing about the matter seems to be that the woman is dead," the Star concluded on Dec. 8, 1899.

Going over the same figures, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser noted the death rate for Hawaiians was triple that of white citizens. "The complete disappearance of the race is only a question of time, and not of a very long time at that," the newspaper predicted. "It is a pitiable spectacle, this passing away of an amiable and interesting people, the more so because the natives could probably save themselves if they could."

Death takes a bite

While the white-owned Honolulu newspapers deliberated the big picture, a few blocks away at the Wing Wo Tai grocery on Nuuanu Avenue, bookkeeper You Chong, 22, may have scratched idly at a flea bite, although it was no more than a passing itch. By then it was too late. The contagion known as Black Death, the bubonic plague, had crossed the Pacific and entered his body.Fleas generally catch plague from infected rats. Plague bacillus multiply so rapidly in a flea's upper digestive tract that it chokes. When the flea feeds upon a host, the dam of swarming bacillus creates a backwash of regurgitated blood, in effect injecting plague like a hypodermic. One bacillus is enough to infect a victim.

The bacillus vomited into Chong's veins by the flea was swept along the currents of his bloodstream, multiplying and settling, like rust, into the liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs and brain. The bacillus attached itself to the body's macrophages, the white-cell soldiers of the immune system, and injected toxins directly into the cells, first a protein that prevents the macrophage from resisting foreign bacteria, then a protein that isolates the macrophage from others, and finally a protein instructing the cell to kill itself. Soon the body is awash in bacteria and dead white blood cells.Maybe a week after the forgotten flea bite, Chong's temperature skyrocketed, peaking at 105 degrees. He began to shiver, his pulse raced liked a runaway locomotive, and he breathed in shuddering gasps.

Dizzy, weary, Chong likely collapsed into bed. It got worse. Nausea wracked his body. He vomited, blood streaking his stomach contents, digestive acids burning his nostrils. His joints felt as if bent nails had been driven between the bones. The muscles of his lower back cramped in agony, and he was unable to control his bowels. Light, any light at all, seemed to burn white-hot, right through his skin. Blistering headaches squeezed his skull; he was giddy, unbalanced, and likely bashed his head against the wall, attempting to crash into unconsciousness, anything to make the fiery sheets of pain go away. If he screamed, the sound spluttered wetly because of a dense, chalky coating plastered like stucco across his tongue and mouth, a grayish-white fur that eventually turned crusty and black.

And then it got worse.

The bacteria multiplied and invaded the lymphatic system, the marrow of the bones, the pericardial sac surrounding his heart. The lymph nodes anchored in Chong's groin, his thighs, his neck, his armpits, began to swell alarmingly, filling with pus from white macrophage corpuscles, serum and plague bacillus.

The swellings, called buboes -- which gives bubonic plague its name -- are the unique symptom of the disease, and grow within hours. Chong's lymph nodes inflated to the size of rotting tangerines, pulling apart the flesh under the skin and splitting it, releasing a vile odor. Blood vessels shredded under the onslaught, and sheets of blood coursed and puddled under the skin. The pooling blood dried and turned black, mottling Chong's flesh like spilled ink. The Black Death is aptly named.

Passage of the disease through the body is fierce and fast. Within three days of first feeling unwell, Chong died as scumming blood burst from his mouth and other orifices. The horrified doctors who examined his body at Wing Wo Tai's grocery had no doubt the most feared disease in human history was established in Honolulu.

Tracking the plague

In 542, the "Plague of Justinian" slammed into Constantinople, killing 70,000 and nearly depopulating the seaport, sometimes felling a thousand victims a week. Smaller outbreaks flared and died in isolation, until the 1340s, when the horror devastated Europe. Entire cities fell ill and died, pyres burned without ceasing, wagons piled with swollen bodies creaked through narrow streets, and the cry of "Bring out your dead!" echoed though the night.And a nursery rhyme was born: Ring around the rosies/pockets full of posies/ashes ashes/we all fall down. The ring refers to inflamed flesh around the rose-colored, bloody buboes, and to rosary beads; the posies are flowers and nosegays carried to combat the odor of putrefying flesh; ashes come from the mass burning of corpses; and we all fall down before Death itself and the wrath of God.

In a five-year span beginning in 1347, 25 million Europeans -- a third of the total population -- fell under the scythe of Black Death. By 1400, 40 million were dead. The horror rattled Western culture to its core. A labor shortage spelled the end of the feudal system as serfs fled for the work in the depopulated cities.

The third great wave of Black Plague upon mankind began in Manchuria in 1890, gradually infecting China, Southeast Asia, India and Japan, crossing the Pacific and flaring up in San Francisco in 1900. An estimated 20 million died.

This time, however, there were the tools of science to combat the disease. There was also a faith in mankind's ability to tame nature. The same blinding self-confidence that hewed the Panama Canal and built the Titanic. There was a natural explanation for plague. It could be stopped if the armies of science could be mobilized.

The power to stop the plague in Honolulu rested with the Board of Health, a genteel organization of bureaucrats, lawyers and doctors largely organized after a cholera epidemic in 1895. The Board's president was Henry Cooper, who had been the government's Attorney General. No one knew the limits of the board's power -- as the century drew to a close, Congress had voted to annex the islands but had not yet done so. Hawaii had a caretaker government that was awaiting U.S. rule. Into this scenario Black Death erupted, its cost in lives and property would not be bested in Hawaiian history until the attack on Pearl Harbor. In both cases, Hawaii mobilized for war.

Search for the cause

The first step was enemy intelligence, and members of the board pored over published reports of plague epidemic in China, Japan and India. Anecdotal evidence established a link between unsanitary conditions and plague outbreaks. Studies revealed rats also caught plague, and the Yersinia pestis bacillus -- looking, under a microscope, like a rice musubi -- was isolated in 1894. Filth equals rats, and in some cases, equals black plague. But were the rats carriers or victims?"All observers agree that the rat is early infected by plague during an epidemic," wrote James Cantlie, a lecturer in the London School of Tropical Medicine in the 1899 winter issue of "The Practitioner," a primary source for Honolulu's Board of Health.

"Many contend that the rat is infected before man, and that the appearance of dead rats about a house forebodes the illness of the inhabitants. Such being the case, it would appear that the rat is the host by which the plague is transmitted to human beings."

Cantlie suggested plague victims be immediately moved to a temporary hospital outside of town, built of flammable materials for quick burning. All in contact with the victim should also be segregated in temporary camps, and their homes disinfected or destroyed.

Untreated black plague is fatal up to 75 percent of the time; the pneumonic version, 95 percent; and septicaemic plague is nearly always fatal.

Pneumonic plague is spread by coughing as the bacteria invades the lungs, filling them with bloody, bubbling liquid. Septicaemic invades through the bloodstream, leading to death within hours, sometimes so quickly the victim's heart simply seizes like a jammed valve and the classic symptoms don't have time to form.

At the dawn of the new century, however, the average American citizen considered black plague a mystery, a blight upon those unfortunate enough to live in squalor, but deadly enough to also reach across class and race distinctions and strike indiscriminately. An epidemic of this disease could conceivably kill everyone in the islands, as there was nowhere to run. Honolulu could become the island equivalent of a plague ship. This vision of bacteriological Armageddon was on the minds of doctors as they viewed You Chong's body on the morning of Dec. 12, 1899.

Within a few hours, four others were diagnosed with the disease and died soon after -- Ching Wy Now, age 45, in Ahi's Furniture Store on Nuuanu Avenue; Yak Hoy, 40, at the Louvre Saloon, next door to Ahi's; Tam Kwock Yee, 44, on Maunakea Street; Nakawaila, a 27-year-old Gilbert islander, in the back yard of a flophouse at Queen Street.

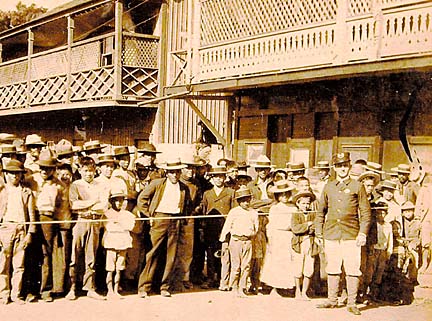

The Board of Health swung into action: passengers aboard ships are quarantined, a quarantine district is established in Chinatown and guards posted, lime is seized to use as a disinfectant, schools are closed and monies supporting these actions were released during an emergency session of the Council of State, Hawaii's temporary government.

A bevy of Japanese physicians, sensitive perhaps to continuing editorial criticism about plague conditions in Japan, presented themselves to the board and volunteered for duty. They already had hundreds of placards printed explaining plague symptoms, leading to suspicions that the Japanese community had already known about the outbreak.

And on the evening of Dec. 12, a Portuguese band slowly wandered the darkened streets of Honolulu, playing funeral marches for the frightened citizens. There was a real possibility few in the city would live to see the new century.

Tomorrow: Lighting the match.

Click for online

calendars and events.