Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

PLAGUE ON OUR SHORES

City at War

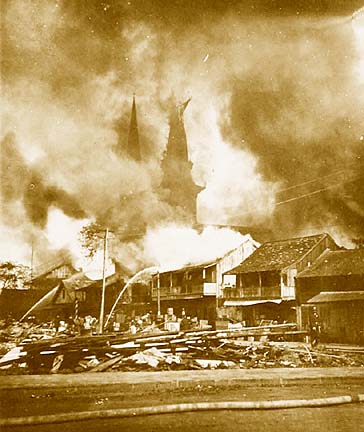

THE GREAT CHINATOWN FIRE

On New Year's Eve one hundred years ago, the first of a number of controlled fires were set in Chinatown as a way of defending Honolulu from bubonic plague, known in history as Black Death. Next to the Pearl Harbor attack, the outbreak of plague was the greatest public-safety disaster in Hawaiian history. The government was determined to do anything to save the city -- even burn it to the ground. Last week we began a four-part series by describing the discovery of plague in Honolulu and the quarantine system set up to contain it. Today's installment chronicles the attitudes that inspired the controlled burning that preceded the Great Chinatown Fire. The series concludes tomorrow.

PART I | II | III | IV | Epilogue

By Burl Burlingame

Star-BulletinIT may have been simple bad luck, or it may have have been a white-dominated business conspiracy, or more likely it fell between the two extremes, but the Chinese residents of teeming Chinatown felt unfairly targeted by health authorities when Black Death erupted in Honolulu at the cusp of the century.

Although thousands of Hawaiian and Japanese were uprooted as the Board of Health methodically began to burn out plague infestations in the quarantine zone, it was Chinese-owned businesses that absorbed the brunt of property damage.

Chinese immigration to the island kingdom climbed steadily until the political coup in 1893 that unseated Liliuokalani. By the mid 1890s, one in five residents of Hawaii was of Chinese descent, and they put down firm roots, establishing schools, newspapers, cemeteries, temples and clan societies. Unlike some other groups of immigrants, however, the Chinese did not assimilate into Hawaiian culture, preferring instead to form a separate society.

This sense of separation was expressed in the Honolulu district known as "Chinatown" where small businesses operated by Chinese ex-plantation workers began to flourish in the 1860s. It is roughly the area bordered by Nuuanu, Beretania and King streets. The area was chockablock with Chinese restaurants, Chinese groceries, Chinese dry-goods shops and other small Chinese industries.In 1886, sparks from a restaurant ignited an enormous fire that leveled most of the district. Excited by the urban clean slate, the Hawaiian government declared new structures had to follow sanitary constraints, were to be made of stone or brick, and considered widening and consolidating the streets. The Advertiser declared they had turned "a national disaster into an ultimate blessing."

It didn't happen. In the 14 years following the fire, Chinatown landowners allowed ramshackle, quickly constructed boomtown wooden buildings to blossom in the area, looming over the narrow dirt streets and overwhelmingly primitive sanitation facilities. The lessons of the 1886 fire were largely ignored.

In 1898, concerned about the swelling tide of Chinese immigration, the Republic of Hawaii evoked the restrictions of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 even though Hawaii was not yet a territory of the United States.More than 7,000 lived in Chinatown's 50 acres at the turn of the century, in an era when no building rose above two stories. Many were Japanese immigrants, jammed in structures controlled by Chinese landlords, who in turn paid Hawaiian and haole landowners.

And Chinatown had become the center of another kind of Asian-controlled business as well. The census taken in December 1899 revealed the area was brimming with organized prostitution, a niche business that provided economic entre for new immigrants. In 1900, 84 percent of known prostitutes in Honolulu were Japanese, and nearly 100 percent of the pimps were Japanese.

Despite the filthy squalor of living conditions, and the disdain with which Chinatown was viewed by the rest of Honolulu, it was an economic engine, pumping money into the pockets of landowners like Bishop Estate. At a time when a plantation worker made about $18 a month, Japanese prostitutes were making hundreds of dollars .

Although maintaining the status quo was lucrative, the overcrowded living conditions in Chinatown, coupled with a complete lack of urban planning for the area, created a neighborhood that ran with rats and insects, that had sewage and garbage lying unattended in the streets. Other residents of Honolulu turned up their noses at Chinatown, both literally and figuratively, while the residents of Chinatown had little choice but to stay where they were. The Advertiser called the district a "pestilential slum."

When the city finally started to build a sewer line through Chinatown in 1899, workers discovered they were digging through compacted layers of fermenting garbage. The intense odor caused diggers to slow to a near-halt.

With the onset of Black Death, a hastily organized troupe of health inspectors went on field trips into Chinatown as if it were a foreign country, and returned horrified. The district, full to bursting with shanty buildings, boarding houses, livestock corrals and chicken coops, reeking outdoor toilets and backyard cesspools, was swarming with rats, maggots, flies, lice and cockroaches. The only solution, it was argued, was a repeat of the cleansing fire of 1886, but this time applied in scientific manner, coupled with military discipline.

The military model was much admired at the time, following the triumph of American forces over the Spanish, and the new conflict involving Great Britain and the Boers was closely followed in Honolulu newspapers. Virtually all contemporary coverage of Honolulu's plague outbreak refers to the "campaign" against the bacillus as "war." And indeed it was -- a fight to the death.

It was in this atmosphere of indignant public opinion that the notion of burning Chinatown for the public good began to take root. What was missing was a legal excuse. An argument on Smith street provided it. A National Guard soldier stabbed a Japanese civilian in the thigh with his bayonet, and fallout from the incident forced the police and the military to determine their jurisdictions.

As Pvt. Hunt explained it, the Japanese attempted to run the blockade; others claimed Hunt had been prodding the man along. The slight wound triggered a reorganization of civil authority, with far-ranging consequences.

At the bottom line was the question of whether Hunt was legally responsible for his actions, whether civil or martial law reigned. After questioning witnesses, police officials decided martial law had not been declared, and the military was called out to assist the police in carrying out civil statutes. In this scenario, both soldiers and police had authority to use force to enforce the quarantine, but that did not give soldiers permission to commit assaults within the quarantine zone.

When this opinion was presented to the National Guard's Maj. Ziegler, however, the commander decided the military, once called to active duty, cannot be interfered with by civil authorities. The military's authority over the quarantine, and over the Honolulu police, was absolute.

Within hours, all Honolulu police were withdrawn from the quarantine zone, and all questions of authority routed to the National Guard. Although martial law had not been officially declared, soldiers were allowed to proceed as if it had. This made it easier to ignore the rules of civil law during the medical emergency that gripped Honolulu. The Board of Health, civilians appointed by President Sanford Dole, lame-duck head of a temporary republic, had absolute power over questions of life and death.

Chinese residents trapped by the city quarantine feared they were being singled out both in life and after death. Chinese immigrants believed if they died overseas, their bones must be returned to China. The Board of Health's solution to plague deaths -- quick cremation -- left no remains for shipping. Horrified Chinese began to hide their ill friends and relatives from authorities. This practice not only exacerbated contagion, but likely obscured the true numbers of plague victims.

A large delegation of Chinese merchants and Chinese consul Yang Wei Pin and Vice Consul Goo Kim met with Henry Cooper, president of the Board of Health, who insisted any decisions regarding cremation would be made by the board. The Chinese claimed the board was discriminating in favor of Japanese, and Cooper responded no Japanese have been diagnosed with plague, and the body of a white teenager had also been hurridly cremated. Cooper suggested they collect the ashes in urns for shipment back to China.

As Honolulu became a city at war, the battle lines of bureaucracy were being drawn. As the Evening Bulletin editorialized, lacking a clear chain of command while details of the new government were being hammered out, President Dole had the authority to appropriate funds to battle the plague. "Let there be no delay," the paper insisted. "This is a time for action, prompt energetic action. The people are prepared to support the vigorous measures which money will forward and which must be set on foot if the battle against black plague is to be short, sharp and decisive."

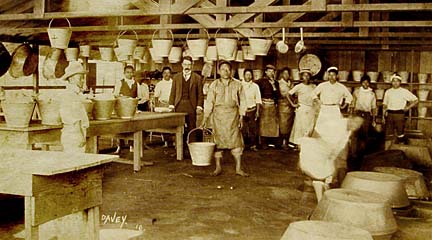

Burning was the apparent immediate answer. A committee of businessmen was formed to find warehouse space for goods removed from Chinatown stores that were being burned down, and during the first three weeks of January, 1900, buildings were torched nearly every day.

A photographer hired by the government recorded pictures of each building, and then it was set alight. Honolulu firemen bookended the flames with streams of water; soldiers and police kept crowds in line and watched for looters.

The newspapers kept track with maps and marveled at the "military" precision of the assault on Black Death. Lists of the dead were daily updated like box scores; by late January, dozens had passed away. The new crematorium on Quarantine Island blazed day and night.

Then five plague deaths within a couple of days occurred near the corner of Nuuanu and Beretania. Clearly, this was a hot spot for pestilence and the government decided to burn it out on the morning of Jan. 20. Four fire engines and every fireman in Honolulu were on the scene, but about an hour into the controlled burning, the wind scattered embers across neighboring rooftops. The wooden roof of Kaumakapili Church with its twin spires, the tallest building in the area, erupted into flame beyond the hoses of firemen.

Helpless, they watched flaming embers, carried on a sudden wind, fly unchecked onto the wooden buildings of Chinatown.

Click for online

calendars and events.