Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

PLAGUE ON OUR SHORES

False Hope

Honolulu fights back

with quarantine and a

makeshift crematoryTHE GREAT CHINATOWN FIRE

On New Year's Eve one hundred years ago, the first of a number of controlled fires were set in Chinatown as a way of defending Honolulu from bubonic plague, known in history as Black Death. Next to the Pearl Harbor attack, the outbreak of plague was the greatest public-safety disaster in Hawaiian history. The government was determined to do anything to save the city -- even burn it to the ground. Yesterday we began a four-part series describing the discovery of plague in Honolulu and the terrible toll it took on its victims. Today's installment takes us through the false hope generated when the epidemic seemed to abate and to the start of what became known as the Great Chinatown Fire. The series continues Monday.

PART I | II | III | IV | Epilogue

By Burl Burlingame

Star-BulletinWITH no crematory in Honolulu, the bodies of the Dec. 12, 1899, plague victims were burned in a spare furnace at Honolulu Iron Works. Within a few days, Iron Works employees constructed a crematorium on "Quarantine Island" for disposing of the dead. Now known as Sand Island, the quarantine was at the time a reeking sand bar surrounded by stagnant salt-water flats, a "wide swamp, filled with every kind of objectionable refuse, including the decaying bodies of animals," observed the Hawaiian Star.

Honolulu's police force was stretched thin by the quarantine. The National Guard was called out in the morning by Col. J.W. Jones to assist police, beginning at the homes of those who died the day before and gradually encompassing the whole of the quarantine district. They were so zealous in shutting down all traffic that firemen in the Pauahi station were unable to receive breakfast or lunch.

An animal menagerie maintained by the Board of Health was used to test the effectiveness of the pathogen. Matter from a plague victim was injected into the animals, including guinea pigs, rabbits and rats. Some animals began dying within hours.

Hearing news of the dying animals, soldiers guarding the quarantine lines pointed out to doctors that while people were locked inside the zone, dogs and cats had free run in and out.

By Dec. 14, due to the quick quarantine and clean-up efforts, there was a cautious sense of relief that the contagion might have been caught in time. No new cases had been reported, those who did die, for any reason, were quickly examined by doctors.

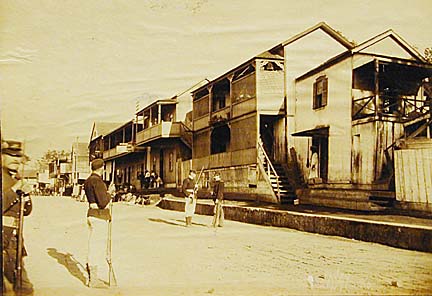

Those trapped by the quarantine began to grow restless due to a lack of food and ungoverned price-gouging on basic foodstuffs within the zone. Business in the zone was suspended almost completely and the streets were deserted except for patrolling soldiers. Even so, inspectors within Chinatown had a difficult time. Often the inhabitants of a building would lock them out, and the inspectors would be forced to smash the door open. Once inside, the inspectors ordered the building's refuse piled in the middle of the street and burned. Often mattresses, clothing and bedding were dumped on the bonfires, which burned continuously, and a pall of greasy smoke wafted down the empty streets.As buildings and yards were emptied out, disinfectants and lime were splashed around, and many structures sported a continuous belt of white lime around the baseboards. Outhouses were burned.

There was a general rush on steamship offices by people anxious to book passage away from the islands. Board of Health president Henry Cooper issued an edict to ship captains; no one is allowed to board or leave the ship, nor can cargo be taken on or off -- particularly Asian cargo -- and any illness on board must be reported to the authorities. If clean for seven days, ships were allowed to sail away from the islands, provided there had been no physical contact with land. To a city dependent on a maritime economy, these measures were like a death threat.

A shed in the yard of Kaumakapili Church was commandeered to serve as headquarters for the volunteers, and equipped with baths and fumigating rooms. All provisions and mail passed through these rooms. For example, on the 18th, 800 letters were fumigated by volunteers wearing "special clothing" to as protection against contagion.

When a week passed without any new cases of plague reported, many were hopeful that the disease was caught early enough to prevent a general outbreak and quarantine could soon be lifted. But then physicians were called to the Iwilei home of Ethel Johnson, 15, in bed for a suspicious disease. Although she had many plague symptoms, doctors were dubious that it could be caught by a white girl who lived outside the quarantined area. They decided to wait and see if she improved.

The Chinatown quarantine was lifted at noon, Dec. 19, to the relief of both those trapped within and to those providing food to the isolated citizens. Board of Health offices were swamped with applications to leave the islands.

That night, National Guard troopers, hearing a disturbance, ascended the stairs at a dormitory on King Street and surprised a Chinese girl on the veranda, who screamed and ran away. They called out to her to have no fear, but she vanished into the night.A few hours later, following violent convulsions, a 14-year-old Chinese girl died in a locked room at a building at the corner of King and Kekaulike streets. Her death was a mystery, for she had none of the usual plague symptoms. Certainly the same girl startled by the troopers, she had a severe skull fracture, cause unknown, and the case was labeled death from "natural causes."

The following day, following complaints from Chinese citizens, an autopsy was performed on the girl who died alone in a locked room. "There was serious derangement of the internal machinery of life," but no signs of plague. The comatose girl, it turned out, had been discovered on the street by Chinese merchants and quietly returned to her room to breath her last. It is believed she leaped from the second story veranda to escape the soldiers and accidentally dashed her head in the fall.

Since Dec. 1, gloomily noted the Hawaiian Star, there had been exactly 100 deaths in Honolulu, the highest mortality since the days of a smallpox epidemic.

On Dec. 23, Ethel Johnson, the Iwilei teenager, died at 1 p.m. and within hours had been dissected by a bevy of doctors. She had unmistakable signs of plague, the first case outside of Chinatown proper, and a military guard was placed on her home.

On Christmas Eve, Ah Fong, a 27-year-old Chinese man, was discovered ill outside of Chinatown and smuggled back inside by friends. By 7 p.m. Ah Fong died at the Kapalama home of a vegetable merchant who fled in terror as his friend began to convulse.

In midafternoon on Christmas Day, 24-year-old Chong Mon Dow died in Pawaa and his wife fled. The couple had been living in a large house with other Chinese vegetable merchants, and when the young man fell ill the other residents placed him in a nearby shack. Later, it was discovered the Chongs lived with 16 others in the same room.

Ko Chun, age about 35, tried to leave Chinatown hidden aboard a carriage, but Hawaiians spotted the obviously sick man and insisted he proceed to the Board of Health office. One look at Ko Chun, and he was placed in the Kakaako hospital, where he died the next day.

Hearing that a young Chinese man, age 25, was ill with plague-like symptoms, inspectors went to his residence in the afternoon and discovered him missing. Neighbors said he had just departed in the direction of the Chinese hospital. When inspectors got to the hospital, they found the man lying dead in the street outside the gate. An autopsy revealed plague, and the body was cremated posthaste.

In a Saturday-night meeting of the board, Cooper targeted the epicenter of contagion as Block 10, bounded by Nuuanu, Pauahi, Smith and Beretania, and urged the complete destruction of the site. It was decided to begin burning down homes and businesses where plague was suspected, cauterizing the city's open wounds.

Board members discussed how best to do this legally, and it was thought that the government should go through a condemnation process, and the inhabitants given a chance to pack up and leave.

Lorrin Thurston, however, argued that plague needed to be dealt with quickly and decisively; anytime a case was diagnosed, the inhabitants were to be dragged out and placed in hospitals or detention camps immediately, and the building burned as soon as it was clear.

The board decided any structure holding contagion should be automatically condemned on the spot, a legal notice posted and the structure burned promptly, including any belongings or furnishings that could not be easily moved.

On New Years' Eve, as the world celebrated the new century, 85 Chinese inhabitants of a building on Nuuanu street were ordered out by militia. Cooper and other members of Honolulu's power structure personally inspected the site and Thurston was placed in charge of moving the evacuees to an enclosed, locked shooting range in Kakaako called the Rifle Butts. Belongings and store goods were quickly tossed onto wagons, doused with lime and hauled away.

By mid-afternoon, with guard ropes up, Honolulu Fire Department wagons were in place and hosing down adjacent buildings while the Nuuanu structure was set ablaze. Despite precautions, a nearby concrete building belonging to a merchant named Ahlo caught fire from flying sparks and began to burn. It was an omen.

The plague continued to claim victims as the fires began to burn. Ah Pow, 24, died on Nuuanu in the morning, the course of the plague so obvious that an autopsy was deemed unnecessary. His body was immediately burned. Quan You Quan, 25, died on King Street, and was also cremated. Kon War, 40, died at the Chinese hospital in Kapalama, and burned the next day.

There were no celebrations recorded in Honolulu that New Year's Eve.

Click for online

calendars and events.