Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

PLAGUE ON OUR SHORES

On New Year's Eve one hundred years ago, the first of a number of controlled fires were set in Chinatown as a way of defending Honolulu from bubonic plague, known in history as Black Death. The government was determined to do anything to save the city -- even burn it to the ground. Last week we began a four-part series by describing the discovery of plague in Honolulu and the quarantine system set up to contain it. The series continued yesterday with a report on the attitudes that inspired the controlled burning of Chinatown. The series concludes today with this installment on the Great Chinatown Fire. At left, read an update on bubonic plague in our modern world.PART I | II | III | IV | Epilogue

By Burl Burlingame

Star-BulletinTHE newspapers of Jan. 20, 1900 were full of breathless descriptions of the day's events, yet at a curious loss of words to describe the magnitude of the catastrophe. The Hawaiian Star settled for one of the great punchy ledes in Hawaiian journalism history. "Chinatown is wiped out," it said simply.

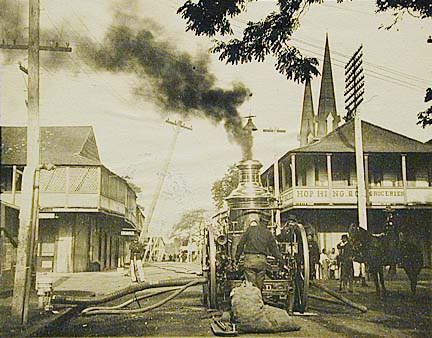

A controlled burning began at 8 a.m. that day with a line of Nuuanu Street buildings near Kaumakapili Church. The Fire Department began by wetting down adjacent buildings, and then started to burn down a single shack next to the church, trying to create a downwind fire break between the Nuuanu buildings and the church. At 10 a.m., however, the steady breeze suddenly shifted and became gusty and erratic, and embers ignited the twin wooden spires of the church, beyond the reach of fire hoses. Flames arced over the street and set off a Chinese joss house on the Ewa side of the church.

As both buildings blazed, firemen frantically attempted to save them, for there were no natural firebreaks between the joss house and Nuuanu Stream, alongside on River Street. Firemen moved Engine No. 1, their primary vehicle, closer to the blazing church in order to better reach the high flames, but the side of the structure exploded and a whirlwind of fiery debris slammed into the engine. Firemen ran for their lives; the firehorses bolted in fear. By the time the trembling horses were captured, Engine No. 1 was buried under blazing rubble, and there was no way to check the onrushing flames.

Like blazing dominos, one after another, buildings began to ignite. Witnesses saw flaming shingles torn from rooftops and carried aloft by smoking tornadoes, then flutter out of the sky onto new rooftops to ignite new fires. Wetting buildings made no difference; the great heat of the firestorm evaporated the moisture as soon as it was applied.Fires began to break out blocks away from the original conflagration, particularly in the midst of the block bordered by Beretania, Maunakea, Pauahi and River streets. Just across Nuuanu Stream was an enormous store of lumber owned by the Hawaii government. It had been purchased to build harbor facilities; much had been appropriated to create the relocation camps. If this lumber caught fire, the fire could burn unchecked for miles, right through the Oahu Railway offices, into Iwilei and the closely built wooden tenements of Palama. A hastily organized bucket brigade doused flaming shingles as they drifted onto the lumber, and the tugboat Eleu forced its way upstream and used its pumps to flood the yards.

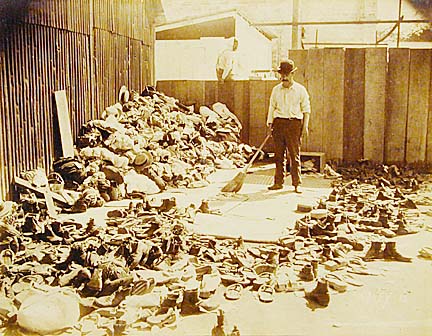

On the River Street side of the stream, the flames reached newly constructed apartments and warehouses, leveling them in minutes. The warehouses contained Chinese valuables removed from previously burned building in Chinatown.

The flames reached for electrical lines. Unwilling to risk live high-power lines writhing in the streets and electrocuting citizens, Hawaiian Electric shut off all power to downtown Honolulu. Without power, however, the telephone system went down and pumps ceased operating. Newspapers were unable to publish. At night there would be no lights. There was no communication with Kalihi and Palama on the other side of the blazing no-man's-land along Nuuanu Stream; the fire also seized and gutted two bridges and a dredging boat moored on the river.

Control by bombing

With only two water engines and one chemical engine, the Fire Department could not hope to contain the conflagration. By noon, officials decided to begin blowing up structures in the path of the fire. Guardsmen lit dynamite and tossed it into storefronts; kegs of gunpowder were rolled into apartments and set off; hidden supplies of fireworks and jugs of kerosene began erupting in the onrushing flames. Chinatown shuddered as explosions shredded buildings, flinging splintered paneling like wooden shrapnel; roofing collapsed onto narrow streets and debris jetted in all directions; bursts of intense flame gouted from windows as glass panes blew out and littered the area with smoking, shattered glass.A group of excited civilians, unwilling to wait for explosives, tore down two buildings on Smith Street with their bare hands, a soda water shop and the office of the Independent, a small newspaper. Although the newspaper owner, a Mr. Testa, managed to flee with his files, fire eventually destroyed his printing equipment.

The firebreaks proved ineffective. Street by street, row by row of crumbled buildings, firefighters were driven back. Flames darted over Pauahi Street, ignited Smith Street, licked ferociously along Hotel Street, leaped across King Street. The flames seemed to ignore wind direction, creating its own currents and eddies of scorching air. A metal building on Smith Street refused to burn, and prevented flames from reaching toward Fort Street. Police had to restrain excited citizens from tearing this building down as well.

The fire turned toward the sea, and ships fled the wharves as sizzling embers rained down on their decks. At Hitch's, a sailmaker's shop on Maunakea near the Honolulu Iron Works, the building positively exploded, and firefighters and civilian bucket-brigades labored feverishly to keep the flames from burning down the Iron Works, as there would be nothing to prevent the inferno from leveling Fort and Queen streets. As long as the fire was moving southwest, it would be hemmed in by Nuuanu Stream and the harbor pier area.The line was drawn at the Iron Works. Hundreds of desperate people used any means necessary to keep the flames contained, buckets, garden hoses, dampened blankets to snuff out drifting embers. Merchants on Fort Street began frantically dragging their goods out of storefronts. Chinatown was convulsing in fiery death throes, and yet it was still a quarantine zone. The inhabitants were trapped. As buildings exploded around them, citizens were prevented from fleeing by lines of troops and police.

The precise burnings of the first three weeks of the campaign had always attracted curious onlookers, and the accidental torching of Kaumakapili Church had been witnessed by the usual knot of gawkers. As the fire spread, many became panic-stricken and tried to remove belongings from their homes, but were prevented by flames or guards.

Residents panic

Screaming mobs of residents charged the quarantine lines and were beaten back by hastily formed ranks of police, military and vigilantes armed with axe handles seized from hardware stores. A cordon of guards was formed along both sides of King Street and refugees were herded toward the grounds of Kawaiahao Church, where they could be isolated within the stone walls. Witnesses were struck by the helpless fear and anger on the refugees' faces as they rescued only what they could carry. Many of the fleeing men were in an ugly, vicious mood, armed with knives and clubs. By mid-afternoon, more than 4,000 citizens were locked up on the church grounds.

Some terrified residents refused to leave their homes even as the buildings caught fire. Authorities frantically searched buildings, carrying out babies and catatonic women and old people weakened by smoke and terror. No one knew if they would survive, and the explosions that shattered the city added to the mounting apprehension. Police and military were split between fighting the fires and enforcing the quarantine lines, and so many were called up so rapidly some were still in civilian clothes. The sight of what appeared to be civilians swinging axe handles at Chinese and Japanese refugees added to the overall hysteria.On the Ewa side of the conflagration, flames leapt twice the height of buildings and pressed more than a thousand refugees against the banks of Nuuanu Stream. Across the river, children were heard screaming, and adults shouting; damning the largely white authorities and government. Firecrackers began exploding in the fires and rumors swept the half-crazed refugees that the military had begun shooting down civilians. Mobs began to break loose and attempt to across the river; they were pushed back by guards. Luckily the flames began to burn themselves out before the entire population was seized by panic.

Chinatown leveled

By mid-afternoon, the holocaust began to gutter. The smoldering neighborhood had been leveled nearly from Punchbowl to the sea, the streets filled with muddy pools, and property and furnishings in sooty, soggy, stinking heaps. Acrid smoke rose in dank mists. At Kaumakapili Church, known primarily as a place of worship for poor Hawaiians, only the fire-blackened stone walls stood, the only recognizable structure in all of Chinatown. A crowd of Hawaiians surveyed the ruins, the women and many of the men in tears. President Sanford Dole was so moved by their grief that he promised a new church would rise in its place.

As the city struggled to cope with the huge numbers of homeless refugees on the evening of Jan. 20, 1900, there was a largely overlooked footnote; only one new case of plague had been reported that day, a Hawaiian-Japanese man named Ahi, who lived near Kaumakapili Church and died that morning at almost the same moment the church caught fire.As the Hawaiian Star summarized that day, when electricity had finally been restored and the presses could run, "In its suddenness, its violence, in its ramifications and widespread danger, in the number of emergencies it created, in the energies it called forth, and in the number of people it affected to point of loss of life or property, there has never been anything equalled to today's fire in Honolulu, and perhaps seldom anywhere else."

Click for online

calendars and events.