HIDDEN WOUNDS • PART 2

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Medics Sgt. Hyun Kim and his wife, Andrea, play with their Nintendo Wii at their home in Waipahu. Kim suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after serving two tours in Iraq and has been on the road to recovery with the help of his wife.

|

|

On the edge of panic

Sgt. Hyun Kim could not shake the memories of his wounded, dying comrades

STORY SUMMARY »

Sgt. Hyun Kim lived through horror in Iraq. As a medic, he functioned on adrenaline and his professional training. But when he got home, he could not shake the grotesque images in his head.

"I started drinking every day," he said. "I was having nightmares, insomnia, flashbacks. Smells would trigger it. If I smelled something burning, I'd think of burned flesh."

His superiors told him to just "suck it up" and threatened to demote him for bad behavior.

Kim did not start healing until he entered the residential recovery program for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder at the Spark Matsunaga VA Medical Center.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

A portrait of Sgt. Hyun Kim and his wife, Andrea, hangs on their refrigerator door in their Waipahu home. "We just noticed he was always sad, coming to work drunk," recalled Andrea, also a medic. "I thought he was a really nice guy. We went to his room and got rid of all of his alcohol and alcohol paraphernalia. We all took turns giving him hugs. ... He just started hanging out with us."

|

|

FULL STORY »

Editor's note: Story contains graphic descriptions of injury.

Shortly after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, 19-year-old Hyun Kim joined the military, figuring he could serve his country and earn money for college.

There were highs in the new job, like when he got to jump out of airplanes during training.

"I love parachuting," said Kim, a Waipahu resident with a compact, sturdy build. "I get a rush out of it."

After he got sent to Iraq, Sgt. Kim thought it was "kind of fun" going on nighttime raids, kicking in doors to capture suspects, SWAT team style.

But as a combat medic, his main job was patching up wounded colleagues and "dealing with mutilated bodies and dead body parts."

Ultimately, those experiences over two tours of duty in Iraq pulled him down as low as he could go.

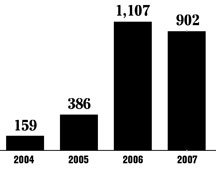

Ailing veterans

Number of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans treated for any ailment by the VA Pacific Islands Health Care System (listed by fiscal year from October to September):

Source: VA Pacific Islands Health Care System

Source: VA Pacific Islands Health Care System

|

In April, a year after leaving the Middle East, Kim cut his wrists, overwhelmed by the aftermath of the war. He had been posted to South Korea by then. In the quiet of everyday life, the carnage in Iraq caught up with him.

"People could be wounded emotionally and sometimes it gets overlooked," said Kim, his black baseball cap shoved low on his brow. "Even though you don't see it physically, it's just as bad. It takes a toll on you gradually, seeing the friends you've been working with dying. It takes a toll."

Before his deployment, Kim had been just a social drinker. After he left the front, alcohol became his steady companion, a futile effort to escape the images that haunted him.

"When I was in Iraq, I wanted to stay there with the unit," he said. "It's when I got back that I started feeling the PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). I started drinking every day. I was having nightmares, insomnia, flashbacks. Smells would trigger it. If I smelled something burning, I'd think of burned flesh."

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

"I don't have nightmares anymore," said Sgt. Hyun Kim, shown searching for a pizza recipe online at home. "They've got me taking these medications. They really work. I used to be on a bunch of medications. I've gotten down to only taking one."

|

|

"I was depressed and I couldn't go to sleep," he said. "I just kept drinking and kept getting more depressed because alcohol is a depressant. If I didn't pass out from drinking, I'd stay up for five, six days, until I'd just be exhausted and crash. And then I'd have nightmares."

No one in his new unit had served in Iraq. "They just thought I was some crap NCO who didn't care about anything," he says.

His superiors told him to just "suck it up" and threatened to demote him for bad behavior.

His first sergeant simply offered this advice, saying it had worked for him after the first Gulf War: "You can exercise it off, you just deal with it, cope with it."

"He only deployed to Kuwait in Desert Shield," Kim said quietly. "I respect him for that, but I'm pretty sure he hasn't gone through the same things I have."

While Kim was in Iraq, he spent much of his time off base, making sweeps for improvised bombs, hiding in the bushes waiting for saboteurs, helping victims of attacks. As a medic, trauma was his regular fare. He functioned on adrenaline and his professional training.

When a rocket-propelled grenade burst through a window late one night, nearly tearing off the feet of his friend and chess partner, Kim dealt with what was left, whipping out scissors to cut through the boots and a dose of morphine to quiet the screams of pain. "It was pretty nasty," he said. "It was like hamburger meat."

Another time, an improvised bomb demolished a Humvee. "Our lieutenant for that platoon lost his arm and both of his legs," Kim said, but survived. Another soldier was torn apart. "Me and some other medic went to go pick up the guy's torso and head, and we had to pick up his arms and legs somewhere else," he said.

"The gunner was missing," Kim went on, his voice flat. "We found him in a stream, pinned underwater. We had to pull him out and put him in the body bag."

Kim tried to focus on the job at hand, even when those around him could not face it. Like when a suicide car bomber blew himself up at a base gate used by Iraqis, killing a dozen people. He and a colleague gave one victim CPR and loaded him into the back of an ambulance.

"I walked around, and there's bodies everywhere, burned, charred bodies," he recalled. "I grabbed a bunch of body bags. I was asking people to help me put them away. People were, like, throwing up. I was picking up body parts and stuff and chunks of flesh."

"After that incident, I just had this smell of burnt human flesh on me for a week. I would take a shower and it would come back, I'd still smell it. It's pretty weird."

BY THE NUMBERS

10% to 15% -- Percentage of soldiers who develop post-traumatic stress disorder after serving in Iraq

20% to 25% -- Percentage of Iraq veterans with PTSD or significant symptoms of depression and anxiety

10% to 20% -- Percentage of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who might have mild traumatic brain injury

Sources: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research; Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center

|

During an R&R break, Kim's relatives in California noticed changes in him. "When I went on leave to visit my family, my sister said I had changed. I was this angry, depressed person," he said. "I used to have really bad road rage."

Kim was in rough shape when his wife, Andrea, first met him. She was a medic, too, and she and her friends did their best to rescue him, trying to steer him away from booze, inviting him to watch movies with them.

"We just noticed he was always sad, coming to work drunk," Andrea Kim said. "I thought he was a really nice guy. We went to his room and got rid of all of his alcohol and alcohol paraphernalia. We all took turns giving him hugs. ... He just started hanging out with us."

Andrea ended up falling in love with the troubled soldier, and they were married, at her suggestion, in January. But Hyun spiraled downward after his chain of command threatened to reduce his rank to specialist. After his suicide attempt, Kim was medevaced to Tripler Army Medical Center for treatment.

"It was a combination of things," he explained. "I felt like I wasn't getting the medical attention I needed. I didn't start getting better until I got here."

COURTESY HYUN KIM

Sgt. Hyun Kim, a U.S. Army medic shown sitting in a Humvee in Kuwait, served two tours of duty in Iraq before post-traumatic stress disorder caught up with him. "I was depressed and I couldn't go to sleep," he recalled. "I just kept drinking and kept getting more depressed because alcohol is a depressant."

|

|

TO GET HELP

VA Suicide Prevention Hotline

(800) 273-TALK (8255), toll-free, 24 hours a day

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Residential Recovery Program at the Spark Matsunaga VA Medical Center

(808) 433-0004

Honolulu Vet Center (Readjustment Counseling Service)

(808) 973-8387

www.vetcenter.va.gov

|

He went through the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Residential Recovery Program at the Spark Matsunaga VA Medical Center, which takes both veterans and active-duty soldiers. That intensive program lasts nearly eight weeks. Participants delve into and deal with traumatic war memories, learn new coping skills and take part in other therapy, exercise and group activities.

"It is emotionally very challenging," said Dr. Kenneth Hirsch, who leads the program. "Many of our patients have said they'd rather pick up a gun and go into combat than to face the emotions we deal with."

The program also helps soldiers gradually learn to handle situations that can seem threatening, from crowded shopping malls to the wide-open spaces of the beach, where some soldiers fear they could be the target of a sniper. The goal is not to erase their wartime experiences, but to help give people tools to manage the fallout.

"They put me in group sessions, where I had to force myself to talk," Kim said. "Getting it out there is kind of a relief."

"In the class I was in, there were two or three guys that were in Vietnam," he added. "To hear their stories, it's like, wow, I'm thankful they have a program like this. Those guys are going through this stuff 30, 40 years after they came back."

Kim, who turned 25 in September, and his 21-year-old bride are finally enjoying their life as newlyweds, furnishing a new home in Waipahu. While he was in Korea, Kim got panic attacks in crowded places like amusement parks. Now he and Andrea go shopping regularly.

"I don't have nightmares anymore," Kim said. "They've got me taking these medications. They really work. I used to be on a bunch of medications. I've gotten down to only taking one."

"He's doing so much better now," Andrea said as she and her husband began making dough for homemade pizza. "We're trying to wean him off the medication because we want to have babies."

‘PTS without The D’ leaves discharged veteran in Limbo

Tattooed on Jon Pajimula's leg are the names of four of the buddies he served with in Afghanistan.

The kind of friends who would share one set of earphones to listen to Hawaiian CDs while camping out in "Taliban-land." Or open up their last can of that hometown delicacy, Spam, when his supply ran out.

All four are dead now, sacrificed one by one on the fields of Afghanistan. Pajimula was wounded and walks with a limp, his knee buckling occasionally. He is not supposed to bend his knee more than 30 degrees, but he has to in order to walk.

The wounds to his psyche hurt more. He feels guilty sometimes that he is still here. His spirit is broken. It is all he can do to get out of bed every day.

"I find little minute reasons," said Pajimula, whose cut-off sleeves reveal dragon tattoos on his arms. "I usually tell myself, the coffee's not going to brew itself, so get up. I keep myself busy doing the littlest things, going to my mom's house, walking her dogs."

"The reason I don't look for a job is because I'm still in the healing process," he said. "This is enough stress as it is. If I get a job at McDonald's flipping burgers and someone complains about his order, that could just be the trigger to make me snap."

"It's a constant daily fight. What am I going to live for today? Why am I going to live?"

Pajimula joined the Army Reserves at age 17, when he was still in Waipahu High School. He served in Bosnia in the 1990s and was sent to Afghanistan as a medic in 2004. His fellow soldiers called him "Doc PJ" because his fellow soldiers had trouble pronouncing his last name.

After 13 years in the service, the sergeant's military career was cut short with an honorable discharge in November 2005 after he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and anger problems. But once he enrolled with Veterans Affairs, he said, he was denied compensation for PTSD. A civilian psychiatrist decided he had "PTS without the D." Although he suffered from post-traumatic stress, it was not enough to be termed a disorder.

"How can I be kicked out of the military as a careerist for something that this other professional said I never had?" asked Pajimula, who has replaced his clean-shaven military look with a goatee. "I don't have a job because I just don't have the motivation anymore. I feel like if I'm going to work hard again, is somebody else going to take that away again? It's very hard to start life from ground zero at age 33."

There is a two-year window of eligibility for free health care with the VA after coming off combat duty.

That deadline expires this month for Pajimula.

Rodney Torigoe, a clinical psychologist with expertise in post-traumatic stress, said such a statute of limitations makes no sense in treating PTSD.

"You don't know when it's going to pop out," he said. "It could be two years from now, or it could be 50 years from now, as we saw with Hurricane Iniki and World War II vets. That's what's unique about this disorder."

U.S. Sen. Daniel Akaka, D-Hawaii, is trying to get the window extended to five years, and recently succeeded in getting an amendment to do so through the Senate.

It will be too late for Pajimula. He lives with a friend and does not see his family these days.

He walks his mother's dogs while she is at work. One of his brothers, an Army officer, recovered from his tour in Iraq in four months and predicted the same for Pajimula. It has not worked out that way.

"The most common question I get after people learn that I'm a combat veteran is 'How many people did you kill?' or 'Did you kill anyone?'" Pajimula said, shaking his head. "Why would anyone ask me that question?"

"I was doing what I knew to do to survive, to come back home," he said. "I don't say, 'I used to be a soldier' anymore, because nobody really cares."