|

Kamehameha

will fight ruling

Its admission policy is

"unlawful race discrimination,"

a federal court rules

The plaintiffs' attorneys say

they will ensure the school

obeys the order

Kamehameha Schools trustees say they will strenuously appeal a federal court ruling that overturns the schools' century-old admission policy giving preference to native Hawaiian children.

The ruling reverses a Nov. 17, 2004, decision by U.S. District Judge Alan Kay that tossed out a challenge to the school's Hawaiian-preference policy. He found that the policy served "a legitimate remedial purpose of improving native Hawaiians' socioeconomic and educational disadvantages."

The John Doe v. Kamehameha Schools lawsuit arose when an anonymous non-Hawaiian student applied to the school twice and was denied after he told the school that none of his grandparents had Hawaiian blood.

Constitutional law expert Eric Grant, of Sacramento, Calif., and local attorney John Goemans, who successfully challenged the Hawaiian-only voting for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in the landmark Rice v. Cayetano case, filed suit on behalf of the student in June 2003 seeking to overturn the admission policy on the basis that it violated the boy's federal civil rights.

Yesterday, Grant said he and his client are overjoyed by the ruling and expect that he will be admitted as a senior when the school year begins Aug. 18.

"If we need to call the court's assistance, we will," he said.

School officials said they would fight any court order to admit the boy.

The court essentially ruled that race and ancestry can no longer be the cornerstone of the school's admission policy, Grant said. It means that Kamehameha will have to fundamentally change its admission policy to be more inclusive rather than exclusive, he added.

Founded in 1884 by the will of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, the Kamehameha Schools is a $6 billion, nonprofit charitable trust that this year will educate about 5,000 native Hawaiian children.

The judges, in their majority opinion, recognized that a non-race-based policy is consistent with the princess' vision of helping disadvantaged students in the state of Hawaii and nothing in the will mandates the current exclusionary policy based on race and ancestry, Grant said.

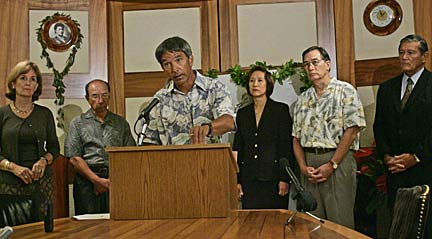

Calling the court's decision wrong, Kamehameha Schools Board Chairwoman Diane Plotts, flanked by the other four trustees, reiterated their resolve to honor the princess' will and continue providing education to thousands of children of Hawaiian ancestry through its preference policy.

Kamehameha Schools trustee Nainoa Thompson spoke at a news conference at Kawaiahao Plaza yesterday after a federal appeals court struck down the school's admission policy. Behind him are, from left, Dee Jay Mailer, CEO; Robert Kihune, vice chairman; Constance Lau, trustee; J. Douglas Ing, secretary-treasurer; and Michael Chun, headmaster of the Kapalama campus.

She said they will ask the 9th Circuit to appoint a larger panel of judges to review the case. If the court agrees, an 11-member panel will be appointed.

"If we have to, we will go beyond that all the way to the Supreme Court," Plotts said. "We are prepared to go as far as necessary to defend our preference policy."

They said they are disappointed that two of the three judges on the panel, Robert R. Beezer and Jay S. Bybee, found that the admission policy was not justified in its exclusion of non-Hawaiians.

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Susan P. Graber wrote that many statutes enacted by Congress show their support for the Kamehameha Schools' policy.

"Congress clearly meant to allow the private education of native Hawaiian children at Kamehameha Schools," Graber wrote.

There is an automatic stay on the 9th Circuit's ruling and the trustees will ask that it be extended until the court rules on its appeal, Plotts said.

Meanwhile, the trustees said they will appeal any decision by the lower court forcing them to accept the boy when the school year begins, Plotts said.

If admitted, the student would be the third non-Hawaiian attending Kamehameha Schools in the past four decades. One is currently attending the Maui campus and another, Brayden Mohica-Cummings, will enter his second year as an ninth-grader at the Kapalama campus.

Dee Jay Mailer, chief executive officer of Kamehameha Schools, said they have no order from the courts to admit the unnamed student.

But if the schools lose their fight against the boy, "we will treat John Doe as we treat all our students," Mailer said.

The court's decision should not affect the students enrolled at Kamehameha Schools, she said.

"We will continue to fight for our rights in the courts to serve those students on our campuses and in our island communities," she said.

There are 5,000 students enrolled on three campuses, including Keaau on the Big Island, Maui and its flagship campus in Kapalama Heights.

Trustee Nainoa Thompson said he was "weakened to the bone" to hear of the court's ruling. But it should serve as a call to the Kamehameha Schools and native Hawaiian community to be strong and stand up for their beliefs.

"This decision is not good for Hawaii, it's not good for native Hawaiians," he said. "But we believe because it is just and we believe it is right, that we believe we're gonna win. ... We're gonna fight."

Members of the native Hawaiian community described the decision as an onslaught against Hawaiians.

Lilikala Kame'eleihiwa of the Center for Hawaiian Studies called the decision "one more theft, one more time white racism wins."

She said in Hawaii, there are only two kinds of non-Hawaiians: the good non-Hawaiians who love native Hawaiians and the bad non-Hawaiians who hate them.

"The good non-Hawaiians would never try steal from us by applying to Kamehameha Schools for anything because they know we have children who need to have that money to go to school and for education," she said.

Vicky Holt-Takamine, president of 'Ilio'ulaokalani Coalition, an organization that advocates for the protection of native lands and native rights, said they are not surprised at the court's decision because the court was not set up to protect the rights of native Hawaiians.

Kamehameha Schools was set up by the princess, who was not American, and was not intended to educate Americans, she said. "It was intended to educate native Hawaiians, the indigenous people of these lands," she said.

Despite the anger, there was some hope in the crowd of about 75 people who assembled outside the trustees' offices after hearing of the court's decision.

Trisha Kehaulani Watson, a graduate of the William S. Richardson School of Law at the University of Hawaii, said the court's decision should be a wake-up call to native Hawaiians to make a stand once and for all "that we are a nation of people who stand together."

"So today, don't see this as a day we lost the 9th Circuit Court's decision," she told the crowd. "I hope five years from now we look back and say this is the day Hawaiians say, 'We have had enough,' and from this day forward, we move as one nation," she said.

If the 9th Circuit rejects the school's request to review the case, the school can ask the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case by petitioning for a writ of certiorari.

Goemans said he doesn't believe the high court will hear it.

The Supreme Court rarely takes up certiorari, Goemans said. In 2000, when the Rice case came up, there were 8,000 certiorari cases and the Supreme Court heard 78, or only about 1 percent, he said.

The facts of the case and the law also weigh against the school, he added.

"The determination is that it's wrong in law and the law is clear there can be do race discrimination in private education," Goemans said.

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]