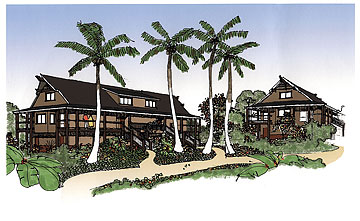

COURTESY MOLOKAI RANCH

COURTESY MOLOKAI RANCH

Molokai Ranch, which bought the Kaluakoi Hotel in 2001, is seeking support for a community based land trust which would fund a $30 million-plus renovation and reopening of the property, shown above in an artist's rendering. CLICK FOR LARGE |

Restoring a Molokai jewel ... but at what price?

Residents and visitors agree they want to see the Kaluakoi Hotel reopened. But they don't all agree on the way Molokai Ranch proposes to pay for it

» FIRST | SECOND OF TWO PARTS

Jim and Lisa Tessener and their children Ben and Malea frolicked in an otherwise vacant pool on a recent Friday at Molokai's Kaluakoi Resort.

The Bozeman, Mont., couple said returning to the resort a decade after honeymooning there to find it deserted and dotted with closed signs was surreal.

"It was booming when we were here last," Jim Tessener said. "It was totally different then. There were tiki torches and music and people everywhere."

Since the Kaluakoi Hotel closed in 2000, putting more than 100 Molokai residents out of work, crashing waves and bird calls have supplied most of the resort's music. The resort's former lobby, bar and restaurant have all shut down, although a small sundry shop, golf course and club still operate.

"We were really disappointed to find out that the Kaluakoi Hotel and most of the amenities had closed," Lisa Tessener said.

Considered to be the birthplace of the hula, a Molokai is place where the people dance to their own tune. About 40 percent of Molokai residents have native Hawaiian ancestry, and many hunt, fish and farm the land for a living. It's a place where merely getting by is good enough and has been for centuries. But even that can be hard without an economic shot in the arm from tourism -- which is why many of the island's 8,000 residents would like to see Molokai Ranch reopen the Kaluakoi Hotel.

Molokai Ranch, the Friendly Isle's largest landowner and employer, has proposed a plan that would refurbish the resort and give back more than 50,000 acres to the community in exchange for the right to turn 500 acres near the federally protected Laau Point into an upscale residential subdivision. Under the plan, the ranch would continue to control 13,880 acres, including the Kaluakoi Hotel and golf course, the Lodge at Maunaloa, and the Beach Village at Kaupoa.

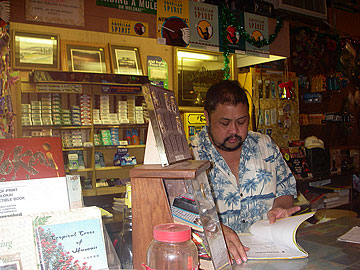

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

A visitor to the resort takes in the beauty of Kepuhi Beach, which fronts the hotel. Much of the 6,700-acre resort has been vacant since the hotel shut down in 2000. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

However, support for an exclusive subdivision near pristine Laau Point, home to crashing waves, vibrant blue waters, golden sands, rocky cliffs and endangered monk seals, is less widespread. The proposed subdivision, a lynchpin of a community-based master land use plan developed by more than 1,000 residents, has been endorsed by the Molokai Enterprise Community, the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs and some residents. Others, such as Hawaiian activist Walter Ritte, see the proposal as the death knell for the island's culture.

"The developers are offering all this candy to everyone in exchange for the heart and soul of Molokai," Ritte said. "Laau Point is the most pristine fishing area in all of Hawaii -- it's how we feed our families. We can't let them give it to 200 millionaires."

Ritte and others who don't want to see any development near Laau Point have formed Save Laau Point to oppose the subdivision. They say the master plan fails to take into account a lack of water on Molokai and future demand from native Hawaiian homesteaders.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Jim Tessener and his daughter, Malea, 5, frolic in the at the Kaluakoi Resort pool, which is maintained for owners and guests of condominum units near the hotel. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

Molokai Ranch's track record on Molokai is also complicated, kamaaina say. While the ranch is known as a generous employer who gives back to the community, many can't forget that the company dredged tons of sand from Papohaku Beach and sent it to Oahu. And, Molokai Ranch, albeit under different managers, once bulldozed plantation homes to make way for a more modern Moanalua Town.

Colette Machado, president of the Molokai Land Trust and an Office of Hawaiian Affairs Trustee for Molokai and Lanai, wants to move past those events.

"I want a future for Molokai. This plan will make that happen," Machado said. "I was once more of an activist than Walter (Ritte). What did it gain us? Just open space that we can't protect from the potential for massive hotel development."

There's an irony to the angst against the plan, Machado said.

"The people who want to intervene against Laau Point were on the committee to get the hotel going. At this point, their argument is all about ego," she said.

Machado and many other supporters of the plan have said that what's really at stake is a healthier economy on the Friendly Isle, where unemployment -- 4.4 percent in October 2006 -- as well as many prices are two to four times higher than the other islands. The population of Molokai has grown from about 6,100 to about 8,000 in the last few decades, but jobs haven't kept pace.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Clayton Pastrana, a clerk at West End Sundries on the grounds of the former Kaluakoi Hotel, has seen business fall by more than 50 percent since the hotel closed. If the hotel reopened, Pastrana said, many of his friends in the visitor industry who had to travel to Maui in search of jobs could return to Molokai. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

"If this plan doesn't go through a lot of my children and grandchildren won't have jobs," said Janice Pele, a Molokai kupuna who support the land trust. "I remember when my brother lost his job at the hotel. It was really rough for my family."

Tourism, thought to be the most viable source of job growth the west end of Molokai, has come with a mixed bag. Total arrivals to Molokai grew 5 percent through November 2006 over the same month the year before, but the 68,948 visitors who came to Molokai represented only about 1 percent of all visitors to Hawaii. Infrastructure costs have continued to rise, but by November 2006, visitor spending on Molokai had fallen 2.8 percent to $29.8 million.

Clayton Pastrana, a clerk at West End Sundries on the grounds of the former Kaluakoi Hotel, can recall what it was like to work at the store in the days when hotel guests frequented the shop along with condominium owners.

"It was at least 50 percent busier. We're looking forward to the resort reopening," Pastrana said. "I was lucky. When the hotel closed down, many of my friends had to go to Maui to find work."

Rob Nedwick, who rents a condo at Kaluakoi Resort, said he is torn in regard to Molokai Ranch's master plan.

"I think it would be beneficial to the community to see the Kaluakoi Hotel reopened," Nedwick said when queried at the resort's sundries store. But, while Nedwick feels that the reopening of the hotel "would be a nice shot in the arm for the local economy," he views the method as "left-handed extortion."

Steve Morgan, a farmer on Molokai who works on Oahu to supplement his income, said he doesn't trust Molokai Ranch.

"They have not been highly motivated to reopen the existing hotel but instead have found it more valuable to use the hotel as a dangling carrot in the form of jobs, with the purpose to help bolster support for Laau development," Morgan said.

There is no guarantee that Molokai Ranch, whose track record for profitability has been spotty in the past and who has scaled back its visitor-camp operation on the island, can make a hotel work, Morgan said.

The ranch has said it cannot pay for the $30 million-plus renovation of the Kaluakoi Hotel without revenues from the sale of lands near Laau Point. Molokai Ranch has estimated that it will cost about $80 million to develop a community near Laau Point, but expects a return of more than $1 million for each of the 200 lots that surround the federally protected lands, said John Sabas, general manager of community affairs for Molokai Ranch.

Richard Cooke III, one of the founding members of the Molokai Land Trust and a developer of Molokai Ranch's master development plan, said the company plays a vital role in the island's sustainability.

"The ranch is important to me and to the community," said Cooke, whose family once owned Molokai Ranch and were responsible for selling lands in the 1970s to the original developers of the Kaluakoi Resort.

"They've been losing money for at least 15 years and it's important that we find a way that they can continue to function and keep their employees employed," he said.

Returning the bulk of Molokai's privately owned lands to the community will help conserve the island's culture and environment, while redeveloping the Kaluakoi Resort and its golf course with funding from the Laau Point subdivision will create at least 100 much-needed jobs, Sabas said.

"We want to protect Molokai and preserve Laau Point," he said.

Since Molokai Ranch filed applications and a draft environmental impact statement with the Maui County Planning Department to create a subdivision at Laau Point, community discussions have heated up. A 45-day comment period on the draft EIS began Dec. 23 and will run through Feb. 6.

Review of the various applications, as well as the draft impact statement, will serve as an important educational process for the Molokai community, said Sabas, who grew up on Molokai and is one of Ritte's childhood classmates.

News of the controversy even reached the vacationing Tesseners by way of the myriad of signs that dot Molokai's houses, fields and roadways between the airport and the resort.

"There's a lot of controversy going on," Jim Tessener said.

Molokai has been dubbed the Friendly Isle, and it is the kind of place where residents wave to passing cars. Still, it's clear that visitors to Molokai can easily overstay their welcome.

Most Molokai residents support a limited visitor industry, where tourists come to visit, not to stay. Most say a small hotel is OK, but they don't want to see development of second-home resort communities that bring increased taxes and infrastructure improvements.

Stoplights aren't currently part of the landscape on Molokai.

"No need," Ritte said. "And, we like it that way."