PART ONE | PART TWO

SIEM REAP, Cambodia » Chuop Thea, a 27-year-old Cambodian woman, once supported her family on $2.50 a day by collecting and selling bamboo stalks before tourism came to her floating village, which sits upon Southeast Asia's largest freshwater lake, the Tonle Sap.

Since Thea began paddling tourists down unspoiled waters to see and hear the bird colonies at the Tonle Sap biosphere reserve, her daily income has nearly quadrupled, taking her well above Cambodia's 50-cents-a-day poverty line

"I am happy to see the tourists come," said Thea, who uses the extra income from tourists to buy rice, fish and spices that supplement meals for her family of five. "When they don't come, I have to sell bamboo or sell my labor to other villages to make ends meet."

During the tourist season, hoards of primary-colored tour boats create wakes in the waters near Prek Toal, their motors splashing the village houses and masking the sound of the birds. A constant stream of new species are continually being discovered in the biosphere, but tourists equipped with motor boats, binoculars, cameras and research logs are among the most predominant. In some cases, they've even come to stay. Intrepid travelers can rent out a village house for a mere $10 a night.

|

That tourists have made it to Prek Toal, an isolated community, speaks to the extent that they have discovered Cambodia, termed "the flavor of the year" by Roland Eng, the country's ambassador at large. Indeed, nothing is sacred from the visitors. While tourism revenue has aided post-conflict development in Cambodia and created new small and micro-business ventures, on the flip side there are plenty of natural and historical attractions at risk of losing their culture uniqueness or falling victim to mismanagement.

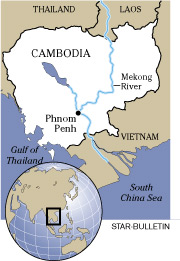

Angkor Wat, the 12th-century temple whose significance places it in the league with other global marvels such as the Pyramids, the Taj Mahal and Machu Pichu, was the first national treasure to draw visitor attention during the last decade as Cambodia began to achieve post-conflict peace. The beauty of Cambodia and of its amazingly resilient people has created a historic, cultural and eco-tourism model that spreads from Angkor Wat and its French-colonial host city to the still-underdeveloped resort beaches of Sihanouk Ville and Phnom Penh, the historic capital city. The intense poverty of post-conflict Cambodia also has created a market for a sex tourism industry that largely preys on young women and children.

Twenty-seven years ago, Cambodians had to fight to preserve their culture as Pol Pot sought to create a total agrarian society by driving people from the cities and killing all the educated, the artists, the musicians, the dancers, the teachers and the trainers. Today, Cambodian host culture is threatened by the country's blossoming tourism industry, which now at $1 billion in annual revenue makes up one-sixth of the national economy.

"Revenue from tourism can reduce the poverty of our people," said Suong Lan, chief of education and training for the Ministry of Tourism's Siem Reap Tourism Office.

Since the late 1990s, Cambodia's visitor industry (largely driven by Angkor Wat and Siem Reap) has been growing by 25 to 35 percent annually. Now, instead of Khmer Rouge, it's the neon-lighted strip malls that advertise wares in English and Chinese, gambling halls, whore houses, obscenely large concrete hotels, karaoke bars and burger joints that could blight traditional Cambodian culture. Unchecked tourists who can't resist touching the chests of the female Apsara dance statutes at Angkor Wat have even buffed the statues shiny and obliterated much of their intricate detail.

Grateful for tourists

Like many other Cambodians, Thea is grateful to the tourists and doesn't really mind the imprint that they leave on her community. As one of the United Nations Development Program's managed resources, the Prek Toal bird sanctuary is one of Cambodia's success stories when it comes to tourism. From 1999 to 2006, the annual tourist count to the sanctuary has grown from 29 to 500, a manageable cap for the area.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Colorful tour boats, above, line the banks of the Tonle Sap waiting to run tourists down Asia's largest freshwater lake. The popularity of this eco-site has motivated tourism officials to set a two-boat-per-day limit within the lake's biosphere region. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

"We want to achieve balance between the tourists and the environment, so since 2004 we have limited the traffic to five or six boats per day," said Lay Khim, an assistant resident representative and environment and energy cluster team leader for the UNDP.

Balance will be important throughout Cambodia as visitor traffic grows, particularly in high-traffic areas like Siem Reap, host city to the Angkor temples. Last year, Cambodia welcomed 1.4 million visitors, and 681,797 of them came to see Angkor Wat. That's 26 times the number of visitors who visited in 1994, just after the country's free election, Lan said.

"In 1969, there were only four hotels in Siem Reap," Lan said. "Now we have 86 with another 17 set to open by the middle of next year."

The mega growth has resulted in hotel overbuilding in Siem Reap and made it difficult for hotels throughout the country` to achieve occupancy above 50 or 60 percent or rake in acceptable levels of revenue per available room, said Jean-Phillipe Beghin, hotel manager of the five-star Raffles Hotel Le Royal in Phnom Penh.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Unlike Angkor Wat, which is mostly intact, many other temples in Cambodia's Angkor Archaeological Park are fragile and in need of constant repair. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

Nonetheless, Raffles and many other prime hoteliers have identified Cambodia as a place with much promise, he said.

"We all think Cambodia has a brilliant future and we want to be here," Beghin said. "The pace of tourists is going to catch up with the inventory soon."

The overbuilding combined with the country's proclivity to court American and Chinese tourists and investors have made it common to see architecture and signage from these cultures in Cambodia. The U.S. dollar is the most commonly used currency in Cambodia, one of the few countries where it comes out of ATMs as often as the riel. And, though it didn't pass, there was talk five years ago to elevate Chinese currency to the same status.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Krista Van der Veldt and Sebastiaan Hermus of Haarlem, Netherlands, take a sobering moment to the column of skulls at Choeng Ek, the Killing Fields. Now a museum, Choeng Ek was once a place of death for thousands of genocide victims. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

Still, there's magic in this place. Angkor Wat, which was built during medieval times, stand testament to the genius and potential of the Cambodian people who once dominated a kingdom that was considered by many in the the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to be considered "the pearl of Asia." The vibrant spring green of the lush rice paddies, the rich blue of the largely unpolluted sky and the mysterious Mona Lisa-like smiles that stretch across the faces that decorate Bayon Temple are beautiful enough to transcend visions of beggar children, burned-out buildings, starving oxen and a nation under the throes of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

"Cambodia is an amazing place. You can still see the stars here," said Julian Blissett, a tourist from China who enjoyed Angkor Wat and Phnom Penh on a recent holiday.

Visitor industry growing

Cambodia's visitor industry was once made dormant by conflict, but everywhere you look there's new hotel, commercial and residential construction. Aside from the sun, sand and surf, Cambodia couldn't be more different than the true paradise that is Hawaii; however, as Cambodia's fledgling visitor industry grows, it will face similar challenges. In order to preserve Cambodia's sense of place, building codes will need to be passed, more Cambodians will have to be educated and trained to assume leadership roles within the visitor industry, crime against tourists and by tourists will have to be stopped, and resource management plans need to be created.

Among these endangered tourist attractions are the Choeung Ek Memorial, otherwise known as the Killing Fields, and Toul Sleng Genocide Museum remnants from Cambodia's darkest days from 1975 to 1979 when dictator Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge party committed genocide on an estimated 1.5 million to 3 million men, women and children.

Only 3 percent or so of the 200 visitors per day who come to see the tower of skulls at Choeung Ek are Cambodians, said Sakona Mom, a tour guide at the site of the Killing Fields, where the bucolic charm of the countryside is broken up by the clothes and bone fragments of Khmer Rouge victims.

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

"Revenue from tourism can reduce the poverty of our people."

Suong Lan

Chief education and training officer for the Ministry of Tourism's Siem Reap Tourism Office

ALLISON SCHAEFERS / ASCHAEFERS@STARBULLETIN.COM

"Revenue from tourism can reduce the poverty of our people."

Suong Lan

Chief education and training officer for the Ministry of Tourism's Siem Reap Tourism Office |

Tourist demand for Choeng Ek has sparked debate about replacing the memorial's pot-holed, red-dirt entry way with a smooth blacktop that tourists can easily navigate. Mom said the infrastructure improvements would be a good move, but there are others, including tourists, who would like to preserve the authenticity of the place.

Krista Van der Veldt and her boyfriend Sebastiaan Hermus of Haarlem, Netherlands, who toured the Killing Fields on a recent Friday, said they are against changes for tourists.

"We read that they want to pave the entrance with asphalt and upgrade this place to make it easier for tourists, but we think they should keep it like it is," Hermus said.

"Yeah, it's not Euro Disney," added Van der Veldt, who was quite contemplative on her second trip to Cambodia, a country with a very high visitor return rate.

"I tell all our friends to visit Cambodia now," Van der Veldt said. "In five years time, I don't think seeing Angkor Wat will be the same experience. It's going to be like the temples in Mexico where you can barely see them because of the hoards of people."

Only 20 guards protect the Angkor Archaeological Park from looters and overzealous tourists, but tourism officials are still debating the merits of setting a daily visitor cap.

"We've discussed a limit of one temple per visitor per day," Lan said. "Right now, ropes and warning signs protect the temples."

Hotel regulation also has been imposed, he said. New Siem Reap hotels can't tower over the Grand Hotel D'Angkor, the historic, five-star Raffles hotel, which sets the standard for all others, Lan said.

Unicef, the National Police Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Women in Cambodia have partnered with developmental organizations and other countries to crack down on undesirable sex tourists. The back cover of Cambodia's official visitor guide, as well as many prominent billboards, advertise that sex offenders who prey on minors will face up to 20 years in a Khmer prison as well as extradition back to their country of origin.

While many are concerned that such regulations will limit visitor traffic to Cambodia, others have criticized the management model for falling short and have argued that unless officials manage tourism better, growth in Cambodia will not be sustainable.

Lessons from abroad

Cambodia could take a lesson from Hawaii, a mature destination that is just now tearing up the concrete jungles that were built during the frenetic past several decades and replacing them with infrastructure that's more in keeping with the host culture.

It has taken Hawaii's visitor industry, a relatively sophisticated market, nearly four decades to realize the true appeal of the islands rests within the host culture and natural resources. Hawaii's tourism officials have discovered that tourists prize experiences over sights.

Judging by the crop of traditional Cambodia experiences springing up for the tourists such as Aspara dance classes, Khmer cooking classes and traditional village accommodations, Kampuchea is on its way to figuring this out, too. But creating a long-term tourism plan that perpetuates its culture and manages its resources could prove challenging for Cambodia, a post-conflict country marked by poor personal self-esteem and a lack of confidence in its leaders. Only time will tell if Cambodia's natural beauty and tremendous assets will prove to be as resilient as her people.

Star-Bulletin reporter Allison Schaefers recently went to Cambodia on a journalism fellowship sponsored by the East-West Center and United Nations Development Program.