"Shelter of Your Burden, Burden of Your Shelter" is by Fred Roster, professor of art in the University of Hawaii Sculpture Program. Roster is among four sculptors chosen to participate in the "Invited Artists" section of "Artists of Hawai'i" -- apart from the 23 artists selected for the juried show.

Free expression

IMAGINE THAT you are invited to be the juror for Hawaii's biggest, longest-running all-media art exhibition of the year, open to all. One day, you get some 1,000 slides of artwork at your door -- 10 to 11 carousels worth of the good, the bad and the ugly. Three hours later it all looks the same -- abstract paintings, clay pots, wire mobiles, junk assemblages, silver gelatin prints, tray after tray after tray of them. How do you decide what to keep?

Artists of Hawaii 2005On view: 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays and 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays through July 24Place: Honolulu Academy of Arts Henry R. Luce Wing first-floor gallery Admission: $7 general; $4 seniors, students and military; under 12 free Call: 532-8700 or visit the Web site www.honoluluacademy.org

|

"My selections were limited to my particular taste or, if you will, peculiar taste at this particular time in my own personal history of art," she writes in the Juror's Statement. "It is a given that all artists make 'magic.' This juror selected those potions that worked for her."

"Magic" seems the right rubric to try to thematize Steinbaum's selections; one definitely senses that delight and surprise were a strong inducement in wading through the oceans of material.

She favored sculptural works with unusual or offbeat use of materials, including a piece of furniture, a weaving made of steel balls, and some wrapped ceramic fish in Styrofoam trays. In painting, she favored the nonabstract and figurative, as well as whimsical, irreverent and cartoonish pieces. In photography, by contrast, the choices are fairly conventional: unaltered black-and-white portraits, landscapes and nature studies.

Steinbaum's gallery once got the "seal of approval" from the Guerrilla Girls, the masked female patrol who call attention to discrimination in the art world, and she is known for her strong interest in women's issues and multiethnic diversity. That interest comes through here in some unusual selections that validate crafty women's media such as beads, thread and sewing patterns, as well as a general leaning toward work that explores the body, culture, themes of displacement and alienation -- work with a strong humanistic bent.

Steinbaum's confident, principled approach -- reflected especially in her decision to favor multiple works by very few artists -- also makes a strong statement about the jurying process itself, calling attention to the fact that any such selection says more about the juror and is more her expression, her show, than any reflection on the individual artworks used to make that statement.

It is a message that is repeated by nearly every juror, says Jennifer Saville, curator of Western art and project director for the annual exhibition.

Artists awardsEdward Aotani: Alfred Preis Memorial Award for Visual Arts for "Untitled"Steve Garon: Jean Charlot Foundation Award for Excellence for "Blizzard, Hokkaido, Japan" Reiko Trow: Cynthia Eyre Award (for a young, emerging artist), for "Running on Empty" Arnold Bornios: Reuben Tam Award for Painting for "Spin Doctors" James Niimoto: Jim Winters Award for 3-D Design for "Links Gift" Trudee Siemann: Roselle Davenport Award for Artistic Excellence for "Birth" Chris Campbell: Melusine Award for Painting for "Fly Like a Butterfly" Marc Thomas: Honolulu Academy of Arts Director's Choice Award for "Untitled" Jeeun Kim: Baciu Visual Arts Award (for visual arts breakthrough) for "Jar Coffin" Elsha Bohnert: John Young Award (for freedom and artistic vision) for "House Arrest"

|

So why do Hawaii artists persist in getting bent out of shape over getting in to "Artists of Hawaii"? Maybe because it quickly becomes clear to any artist, whether from here or elsewhere, that these juried exhibitions -- Honolulu has three major ones, and a handful more in specific media -- represent the golden gateway to "making it" in Hawaii's art establishment: attention from critics and art collectors (notably the state Foundation on Culture and the Arts), and a shot at someday having a show in one of the three main art museums.

Saville explains Hawaii's strong reliance on juried exhibitions thus: "Since there are so few opportunities for a local artist to exhibit, it might be that a juried show is a means of democratizing the whole opportunity to present artwork; that rather than the few venues we have focusing on a few solo or two- or three-person shows, a juried exhibition gives a greater opportunity to a greater number of artists, and also to our viewing public."

But the juried exhibition is "democratizing" at another level as well: Over time, certain artists will tend to be chosen more often. They might not necessarily be those with the widest appeal, because many such artists move off island. But eventually it will become clear who the Artists of Hawaii really are -- the ones who have made a commitment to this place, who have figured out how to be selected often. And then it becomes clear also to buyers, curators and any others who seek a sound investment in tomorrow's Satoru Abes and Toshiko Takaezus, whose work it is worthwhile and safe to collect.

Last year's juror, senior editor of Art in America Janet Koplos -- who, like many of the jurors, had little previous exposure to art in Hawaii -- noted that she saw in the entries "little of certain kinds of art common in New York ... angry or cynical work, nor did I find much vulgarity or harshness." She attributed this to Hawaii being "a more pleasant place to live than New York."

But it is also true that in New York or London or Los Angeles, graffiti and street performance and noise can be considered artistic forms of expression, whereas in Honolulu they are just crimes. It is because New York curators dared to mount on their museum walls a Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cy Twombly or Jackson Pollock that art audiences everywhere were jolted into expanding their understanding of what is considered art. Such cities represent the "leading edge" in the arts because they have art institutions that push the boundaries of the comfortable, the known, the proven, the safe, and force people to look at things in a new way.

In Hawaii, by contrast, any artist who does something new and difficult to understand -- not to mention angry, cynical or vulgar -- will quickly learn not to bother entering juried exhibitions. Even if a juror does make daring selections in any given year -- which is unlikely, given that the context of choosing from a mass of entries is not the same as seeking out what's happening in the studios -- the long-term impact on the Hawaii art scene is guaranteed to be negligible. While this is a shame for art audiences here, it probably comes as no accident.

Chris Campbell's painting "Modern Cat" realistically portrays both viewer and the viewed.

The handful of names chosen are always familiar to the arts community and rarely include a dark horse. A substantial number are members of the University of Hawaii art faculty -- but long-term artistic achievement and teaching contributions in the state will never get certain people selected, while others will find a place in the pantheon every few years.

Chosen to participate this year are four sculptors -- Sean Browne, whose bronze sculptures of King Kalakaua and Prince Kuhio stand in Waikiki; Fred Roster, professor of art in the University of Hawaii Sculpture Program; Frank Sheriff, a lecturer in the UH Sculpture Program; and Shigeharu Yamada, a retired UH professor. Roster and Sheriffer are Jean Charlot Award winners; Browne and Yamada have been named Living Treasures by the Honpa Hongwanji Mission.

This juxtaposition, little-known artists and Invited Artists, offers an object lesson in what is really being presented at the "Artists of Hawaii," even more than any particular juror's vision. The Invited Artists represent the crowning achievement of a journey that begins with consistent selection in exhibitions, and keeps its eye on the ball of acceptability.

They might not be the islands' most enduring or progressive artists -- though some certainly might be. The bottom line is they fit in, meaning they have enough invested in the system -- a crucial factor in rising to the top of so many Hawaii institutions -- to be depended on to flatter and preserve it.

As juror in 2003, then-director of the Honolulu Academy of Arts George Ellis noted that art exhibitions originally served to validate ruling political institutions. "Artists of Hawaii" offers an annual mechanism to guarantee that in Hawaii they still will.

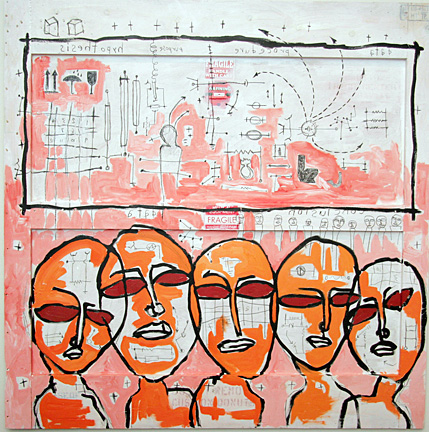

Arnold Bornios' "Spin Doctors" won the Reuben Tam Award for Painting.

Reiko Trow's "Running on Empty" won the Cynthia Eyre Award.

E-mail to Features Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]