Study on isle ice users

reveals poverty and

Hawaiian ancestry

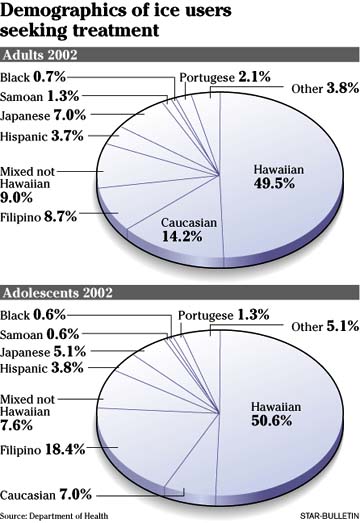

The majority of people who have sought treatment for ice addiction in the past five years say they are of Hawaiian ancestry, according to Department of Health statistics.

In 2002, 49.5 percent of the people who sought treatment in community-based programs with some state funding were Hawaiian. The next closest ethnic group, Caucasians, amounted to 14.2 percent of those who sought treatment.

These numbers do not account for all of the people treated for ice addiction in the state. As a result, they are skewed somewhat toward lower socioeconomic groups, which historically have included a disproportionate number of Hawaiians.

The state figures are a compilation of admissions data from all community-based treatment centers that get some state alcohol and drug-abuse funding.

The figures, then, include someone who goes to Hina Mauka Recovery Center, regardless of whether they get private insurance or state aid, simply because Hina Mauka as a whole gets some state aid.

The state numbers would not detect someone, presumably from a higher economic strata, who is privately insured but goes to the mainland or to a private therapist for treatment.

Some researchers say that although ice is used across many ethnic and socioeconomic groups, it seems most heavily used among "vulnerable populations," particularly in poor communities with little hope of jobs or a better life.

"They're self-medicating," said Alice Dickow, a scientific researcher and the former executive director of the Women's Addiction Treatment Center at St. Francis Medical Center. "This drug is so seductive to people who have been marginalized. It gives them energy, improved feelings of confidence and feelings that they have all this power and are in control of their circumstances when they are not."

Dickow is an investigator with the federally funded Methamphetamine Treatment Project, which has studied ice use in eight cities and compared users and treatment outcomes. Dickow was the principal investigator for the Hawaii site of the study that compared socioeconomic factors but did not identify ethnicity.

Dickow's study found that most Hawaii users had tough socioeconomic problems and that they had been addicted far longer than their mainland counterparts.

Dickow said she tried to recruit a broader socioeconomic profile of users but was unsuccessful.

"The people showing up for treatment have multiple problems and have been referred to treatment by court orders or CPS (Child Protective Services)."

She said "there is a broader social context of long-standing problems that may create the conditions for people to turn to meth."

Dickow's study paints a profile of the ice addict as someone with many problems of which drug addiction seems another symptom. She found higher levels of unemployment, lower income levels and higher incidences of abuse. About 55 percent of the participants in her study, which offered treatment, were women.

"Treating them for drug addiction is only treating one of their problems," said Dickow. "The solution needs to go beyond just treating drug addiction to the larger social context."

The average Hawaii user was 33 years old and had been addicted for 11.5 years, compared with 7.54 years on the mainland. The average Hawaii user started use at age 21.

"We have people who have used it longer and more regularly than users on the mainland," said Dickow. "They use meth regularly, not like a drug with bingeing. They use it like a way of life, like drinking coffee."

She added, "Overall, the women in our sample also had more psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, psychosis and problems with violence."

Dickow found that 49 percent were unemployed compared with 23 percent on the mainland. The average income was $220 a week in Hawaii compared with the mainland average of $625.

She found that more Hawaii users had experienced sexual and physical abuse. For example, 18 percent of the Hawaii group had experienced physical abuse within the past 30 days compared with 8 percent of the mainland sample. About 26 percent of the Hawaii sample reported being the victim of sexual abuse compared with 20 percent of the rest of the sample.

As for treatment, Dickow reported the Hawaii sample did far worse than mainland users. Within the first four weeks of a 12-week treatment program, 70 percent of the Hawaii sample had dropped out.

Treatment counselors often talk about the patient's "readiness" to get off a drug and reclaim their lives. The problem, Dickow and others see, is that some use meth to escape their lives and are not motivated to reclaim them.

"So we take away their coping drug and just send them back into their communities where the same problems are still there," said Dickow.