Isle schools avoid

serious crimeAn emerging standard for

"persistent" danger is based on

violence and gun possession

Starting next month, federal law requires the states to identify "persistently dangerous" schools and give students a chance to transfer to safer ones.

Why teaching and learning at Hawaii's public schools can be more difficult than it should be.

Under a definition adopted by Hawaii's Department of Education, none of the state's 283 schools qualifies for that title.

"We're not even close in any area," said Kendyl Ko, educational specialist for the Safe and Drug Free Schools program. "If a school should come close to meeting the criteria for one year, that would mobilize our people to get into the school and help them turn the trend around."

A committee of parents and educators worked with the department to develop the definition, which is being submitted to the federal government for review.

Under the proposed definition, schools would be labeled "persistently dangerous" if they meet two conditions for three years straight:

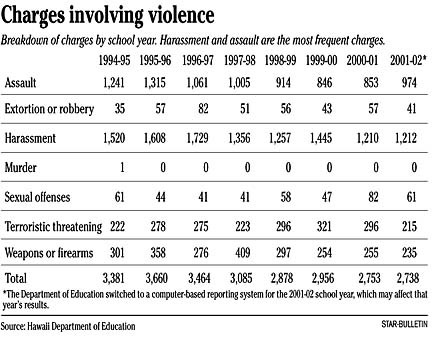

>> At least 1 percent of the student body suspended for 92 days or more for firearms violations.Ko said the department decided on long-term suspensions to ensure serious offenses were involved, not just playground fights, and a three-year period to show it was a "persistent" problem. California's definition is similar, using 1 percent of expulsions for serious offenses, over a three-year period.>> At least 1 percent suspended for 92 days or more for assault, murder, robbery, sexual assault, terroristic threatening and possession or use of firearms, dangerous weapons or instruments.

Just a tiny number of suspensions in Hawaii last as long as 92 days -- an average of 78 annually over the last three years out of a student population of roughly 184,000, according to Thomas Gans, evaluation specialist for the Department of Education. No school reported more than two-tenths of 1 percent of its students with 92-day suspensions, and only a few schools reached even that level in any of the three years.

Karen Ginoza, Hawaii State Teachers Association president, said that using disciplinary data to gauge whether schools are dangerous may not be accurate, and labeling schools on that basis might encourage principals to hush up violent offenses for fear their schools will get a bad name.

"Principals are going to be reluctant to report incidents because it makes the school look bad," she said. "We're actually going to diminish the reports."

William Modzeleski, director of the Safe and Drug Free Schools Program in the U.S. Department of Education, said many states are relying on suspension and expulsion data to identify dangerous schools because it is readily available and quantifiable. He said he does not think that it is likely to lead to underreporting.

"These are serious crimes that are hard to sweep under the carpet," he said. "We're talking about crimes that result in serious injury or death."

The Gun-Free Schools Act requires that states suspend students found with firearms from school for a year, unless there are extenuating circumstances, and report such offenses to the federal government.

Hawaii's most recent report, for the 2001-2002 school year, lists six incidents that meet the federal definition of "firearms." One student brought a gun to Castle High School; the rest involved explosives, including fireworks.

There were 29 incidents under the state's broader definition of firearms, which includes air guns, BB guns, pellet guns and paint guns. The broader category will apply when determining what schools are "persistently dangerous."

Ginoza suggested that the department should take into account teachers' and students' opinions in defining dangerous schools.

"You've got to talk to the kids and teachers because that's where the problem is," she said. "It has to be much more qualitative, where principals and teachers are not afraid to report."