HAWAII'S PUBLIC SCHOOLS

GEORGE F. LEE / GLEE@STARBULLETIN.COM

Though there are concerns about violence in Hawaii's schools, data show that the situation is improving. "We don't have the rapes, shootings and stabbings that you find in large urban centers, thank God," said Joan Husted, teachers union executive director. Shown is Radford High School during a bomb scare.

Safer to enter?

Despite a few bad incidents,

teachers and students say

they feel secure

Counselor Robert "Bobby" Cardozo says he was standing in a walkway at Lahainaluna High School when a student rammed him like a linebacker, then kept walking.

Why teaching and learning at Hawaii's public schools can be more difficult than it should be.

As Cardozo called out to him, the boy's older brother slammed into the counselor from behind, knocking him down a ramp, he said.

"From the force I felt, he had to have been running at me," Cardozo said. "I went flying. I landed about 10 feet away."

Six months later, Cardozo still has scars on his legs and elbows from the attack, he said, and has undergone back surgery for a ruptured disk. He did not know either boy, but apparently had jostled one of them a few minutes before he was assaulted.

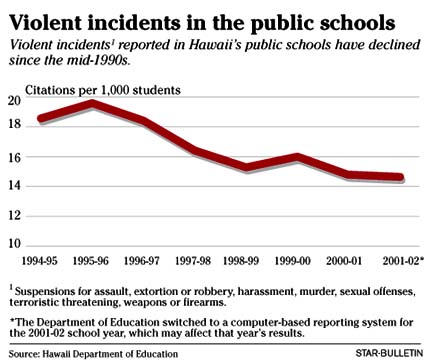

Cardozo's experience and an attack on two teachers at Waianae High School in May have raised questions about whether violence is rising in Hawaii's public schools. Getting a clear answer is challenging, with close to 184,000 students in 283 schools across the state, and conditions varying from campus to campus. But data collected for the system as a whole suggests that things have improved since the mid-1990s.

Citations for violent offenses peaked during the 1995-1996 school year at just less than 20 per 1,000 students, and leveled off at close to 15 in the most recent years available, according to Department of Education statistics. Figures have not yet been compiled for the school year that just ended.

Those citations are for assault, extortion or robbery, use or possession of dangerous weapons or firearms, harassment, terroristic threatening, sexual offenses and murder. Harassment, which includes verbal abuse, is the most common, followed by assault.

The school system switched from a paper-based system to computerized tracking of disciplinary data starting in the 2001-2002 school year, so that year's figures may not be comparable with previous ones, according to Thomas Gans, evaluation specialist for the Department of Education. Assaults increased 14 percent that year to 974, while harassment stayed stable and the other offenses declined. The assault figure remained well below the 1,315 reported in 1995-96.

"I would never make a judgment based on one year," Gans said. "What we might be seeing in last year's assault figures is either a blip or, for some reason, an increase. I certainly don't see any wave of violence. What I see are fluctuations."

Disciplinary data are just one way of tracking violence in schools, and may not accurately gauge safety levels on campus, in any case. High suspension rates could signal rampant misconduct or a low tolerance for misbehavior. Conversely, low rates could reflect better-behaved kids, or principals failing to crack down on misconduct.

The overall trend, however, is echoed in another measure that has no connection to discipline. High school students, responding anonymously to the biannual Hawaii Youth Risk Behavior Survey, are reporting fewer fights on campus. The percentage who said they had been in a physical fight on school property within the past year dropped from 14 percent in 1993 to 11.5 percent in 1999.

In 2001 the figure was 9 percent of the 1,080 Hawaii students surveyed. Hawaii's responses to the question have run roughly two percentage points lower than the national average in the survey, which is sponsored by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Neither the Hawaii State Teachers Association nor the Department of Education tracks assaults on teachers specifically, but HSTA Executive Director Joan Husted said one or two serious instances are reported each year.

In May a 17-year-old student at Waianae High School allegedly grabbed his special-education teacher by the hair and forced her to the ground, bumping her head, then kicked another teacher who tried to intervene, police said.

Such assaults are rare enough that the HSTA dropped a question about safety from its teacher survey this year.

"Our earlier surveys keep showing that teachers don't feel physically afraid," Husted said.

Cardozo, who was in his first year as a counselor at the Lahaina school, said he does not hold a grudge against the two boys and would like to return to his job. But he considers discipline lax in Hawaii's schools.

"A system needs to be implemented where kids don't feel they can get away with that sort of thing," he said in a telephone interview from his home in Mesa, Ariz., where he returned for surgery. "There's a giant difference in how they handle discipline in Hawaii and the mainland. Kids who would do that here would be expelled immediately."

The boys, ages 16 and 17 at the time, were suspended from school for 30 days and 45 days.

Their parents, Keeaumoku and Uilani Kapu, protested the suspensions as too harsh. They say Cardozo provoked the situation because he did not apologize for bumping into their younger son, and that the older boy was just trying to protect his brother.

"It wasn't their fault," Uilani Kapu said in a phone interview Wednesday. "The counselor, being a counselor, should have handled it appropriately. He was yelling and going after my son. My older son heard all the commotion and pushed the counselor. My son didn't even know who he was. It just escalated."

Hawaii's public schools must abide by a common disciplinary code that spells out infractions and possible consequences, but principals have discretion in meting out punishment. The exception is firearms violations, which under federal law are supposed to result in a year's suspension from school, unless the superintendent finds there are extenuating circumstances.

"How safe are our schools? It depends what thermometer you're using," Husted said. "We don't have the rapes, shootings and stabbings that you find in large urban centers, thank God. But there is shoving, there is pushing, there are people having their lives threatened.

"The majority of teachers don't face that, but enough do that we expect the DOE to put a stop to it."

Because infractions from harassment to assault violate state law, some people advocate reporting trouble to the police as well as the principal.

David Gold, an English teacher at Waianae High School, said more teachers and parents need to press charges against students in serious cases.

"For us to create a safe school environment, everybody has to take a certain responsibility," said Gold, who worked with troubled kids before joining Waianae's faculty four years ago. "When it's a crime, people need to press charges. I think that would probably go a long way toward reducing it."

"Where teachers are threatened and don't do anything about it because they don't want to make waves, that's really not doing anyone any favors," he added.

He said inexperienced teachers are often paired with students who are struggling and frustrated in school, because those are the positions that are open, but the combination can be volatile. New teachers need more support and help learning ways to deal with students "in a positive, nonpunitive way when it's possible," he said.

In the last several years, the Department of Education has focused attention on trying to prevent outbursts before they happen. An approach known as Positive Behavior Support, developed at the University of Oregon, started at a handful of schools in Hawaii in 1996 and has spread to 180 schools in the state, according to Jean Nakasato, educational specialist for discipline and character education.

Each school adopting the system sets clear expectations for students and collects data to hone in on specific problems. Teachers and staff are supposed to reinforce the right behavior, to "catch students being good." They try to prevent misconduct by tracking precursors to it, intervening before things escalate and making consequences consistent.

"I don't think the public has realized the impact that positive behavior support has started to have," Nakasato said. "Schools can focus their efforts and be proactive."

Preliminary data show the system helps cut the number of teacher referrals for misconduct as well as suspensions, she said.

Superintendent Patricia Hamamoto has directed that it be extended to all schools.

The Legislature also launched a pilot program of school safety managers at 23 Oahu schools three years ago, and has budgeted money to extend it to 70 middle and high schools statewide next year. Unlike school security attendants, the professional safety managers are supposed to look at the big picture and zero in on problem areas. All have at least 20 years' experience in law enforcement.

"Everybody across the nation is struggling to figure out what to do to make campuses safe without making them look like prisons," said Meda Chesney-Lind, a University of Hawaii criminologist who is evaluating the safety manager program.

"I think the Department of Education is headed in a promising direction, at least as far as our early interviews with principals, students and safety managers," she said, applauding the department's "balanced approach" to safety.

Ashley Olson, who teaches French and Spanish at Lahainaluna, said she was appalled by what happened to Cardozo. "That was a really shocking incident," she said. "It should never have happened, ever."

"I think as a society, we are significantly less disciplined than we were 20, 30 years ago, and that shows up in the schools," Olson added. "But most of our kids at Lahainaluna are wonderful. When I had carpal tunnel release surgery, students came to my home with get-well cards and chicken soup."