SPECIAL REPORT

Last Of Three Parts

|

Secrecy shrouds Compared with the rest of the country, Hawaii has one of the more secretive systems for investigating lawyers accused of unethical conduct.

ethics investigations

Some critics say the current system

Statistics on lawyer sanctions

hides information on conduct complaints

Oregon’s attorney complaints open to all

By Rob Perez

rperez@starbulletin.com

It is secretive enough that an attorney can receive multiple minor sanctions and you couldn't get access to that information, even if you were considering hiring the lawyer.

A three-part series

Day 1 | Day 2Or the attorney could be formally charged with a serious ethics violation, and you would be completely in the dark about it.

That bothers critics.

"It's bothersome in the sense that there is potentially highly relevant information that is not available to the general public when selecting an attorney to handle important affairs," said Evan Shirley, a lawyer who has written about Hawaii's ethics system.

Proponents say some measure of secrecy is needed to balance the public's right to know with the rights of an accused attorney, particularly because filing a complaint is as simple as writing a letter. The complainant also has absolute privilege against being sued, even if information in the complaint is false.

Yet Hawaii goes much farther than at least 37 states when it comes to protecting the privacy of an accused attorney.

In those states, complaints against lawyers become public once the investigating agency establishes probable cause and files formal charges, according to the American Bar Association, the profession's nationwide trade group. One state, Oregon, makes complaints public from the get-go.

In Hawaii, however, the Office of Disciplinary Counsel, which operates according to Hawaii Supreme Court rules, keeps proceedings confidential until a public sanction is recommended or the disciplinary board publicly reprimands the attorney.

Often that happens at least a year to two years after the formal complaint, called a petition, has been filed.

Critics say that is way too late in the process and only fosters suspicion in a disciplinary system dominated by attorneys.

Hawaii residents, like those in the 37 states, should be able to learn whether a lawyer is the subject of a formal complaint, especially one that already has gone through a weeding-out process and is determined not to be frivolous, the critics say.

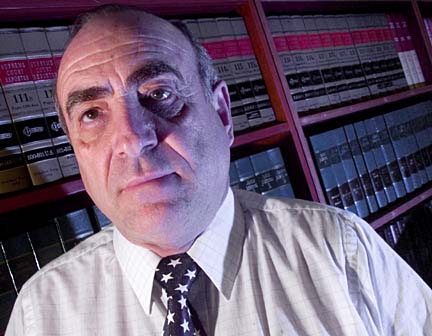

"What we have now is a very bad system," said Earle Partington, an attorney who has represented lawyers facing charges before the ODC.

But proponents say it works well and provides proper balance between the rights of the public and the attorney.

The current system, they note, allows the board to dismiss the complaint even after the petition is filed if further investigation shows insufficient evidence to proceed. That, however, happens rarely.

"If it's (public) too early, the people who are good lawyers but have wrongful accusations against them get thrown into the soup with everyone else," said attorney David Louie, past president of the Hawaii State Bar Association.

|

To put the issue into perspective, consider this:Typically, only 1 percent or less of Hawaii's 3,800 practicing attorneys are sanctioned in a given year.

Since 1995, about 65 percent of the 265 lawyers who have been punished were done so privately, according to ODC figures. Private sanctions are given when the ODC staff or board believes the misconduct is minor -- often a first-time offense -- and does not rate a public punishment. An attorney, for instance, can be given an informal admonition for failing to timely file documents in a court case and failing to respond to the client's request for information.

The sanction remains part of the attorney's record. The public just does not have access to that information, even if the attorney has accumulated several admonitions.

In five states and the District of Columbia, private sanctions are not even permitted. All lawyer discipline in those jurisdictions is public, according to the American Bar Association.

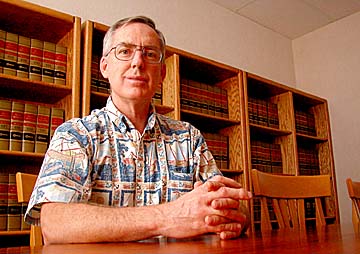

UH law professor Randy Roth, who headed the state bar in 1999, said he raised the idea during his presidency of the local organization pushing for a more open system, believing that would foster greater public confidence in the process.

The idea died for lack of interest.

"I determined it had a snowball's chance in hell of getting anywhere," Roth said.

Carroll Taylor, chairman of the ODC's disciplinary board, said the use of private sanctions gives the agency flexibility to relatively quickly dispose of minor cases involving attorneys who want to keep the matters confidential. By settling those cases, Taylor said, the ODC can concentrate on the more serious ones.

"It relieves the board from having to prove and litigate every matter of probable cause," he said.

The secrecy of the system, though, is not the only issue drawing criticism.

The vast majority of sanctions involve solo practitioners or lawyers from small law firms, raising questions of whether attorneys from large or politically connected firms get special treatment, especially in the pre-screening of complaints. Some wonder whether cases involving prominent lawyers are too easily dismissed.

"It's so secretive, we can't say for sure," Partington said. "But anyone who believes the system provides an unbiased review of complaints is in cloud cuckoo land."

Carole Richelieu, chief disciplinary counsel, denies that anyone gets special treatment. "That's pretty silly."

Taylor, the chairman, said the board is not gun-shy about sanctioning prominent attorneys if they break the rules.

A lawyer from a prominent firm, in fact, recently was given an informal admonition, he said. Taylor could not provide details because of the confidentiality rule. But the person who initiated the complaint later wrote the Supreme Court to complain that the attorney got off easy because he was from a large firm, Taylor said.

Shirley, the attorney who has written about the ethics system, said large firms usually have a variety of internal controls that would prevent ethics problems from reaching an agency like ODC.

Moreover, an agency with limited resources tends to focus on cases involving solo practitioners or small firms in much the same way police departments focus their efforts where they will more readily pay off, Shirley said. "It's easier to go after street crime than white-collar crime."

Another common complaint about the disciplinary system is that the process takes too long. Some cases drag on for several years, and the effect on the accused can be devastating, say several attorneys who have gone through the process.

"You get hung out to dry," said one lawyer. "You become untouchable."

Taylor acknowledged that cases need to be resolved more quickly. That's something the ODC is working to improve, he said.

But a growing caseload has not helped.

When Richelieu joined the agency in 1989, staff attorneys handled 40 to 50 cases each at any given time. Today that load has swelled to roughly 100 to 120 for each of the five attorneys on staff.

For major changes to be made in the system, the Supreme Court would have to modify or issue new rules.

Despite the criticisms, many in the legal community give the system and the ODC high marks. The fact that Hawaii had the highest disbarment rates nationwide in 1998 and 1999 is a testament to the effectiveness of the system, they said.

One of its strengths, they add, is having a disciplinary board with seven of its 18 members as nonattorneys. That helps bring balance to the discussions and counters the perception that lawyers are simply protecting their own.

Said retired accountant Richard Coons, one of the board members, "The system works very, very well."

BACK TO TOP

|

The majority of lawyers who engaged in misconduct received private sanctions over the past seven years. When a lawyer is sanctioned privately, that information in confidential. The numbers: Public vs. private?

YEAR PUBLIC PRIVATE TOTAL 2001 10 20 30 2000 13 22 35 1999 19 21 40 1998 14 30 44 1997 16 12 28 1996 11 33 44 1995 8 36 44 Total 91 174 265

BACK TO TOP

|

If Hawaii has a system steeped in confidentiality, Oregon's is an open book. Oregon’s attorney

complaints open to allBoth allegations and discipline are

made public under the law

By Rob Perez

rperez@starbulletin.comA wide-open book.

No other state, in fact, has a lawyer discipline system as accessible to the public as Oregon's, according to the American Bar Association.

As soon as a complaint alleging an ethics violation is filed against an Oregon attorney, it is public. So is any discipline that may result.

Hawaii waits until a public sanction is recommended or a public reprimand imposed before a case becomes open.

The majority of Hawaii's discipline cases typically are private -- hence, secret -- because they involve only minor infractions.

Both states give the person filing a complaint absolute immunity from lawsuits over what is in the complaint, even if the information is false.

The idea is to encourage people who may be intimidated by the process or by the attorney to report unethical behavior without fear of being sued.

Jeffrey Sapiro, disciplinary counsel for the Oregon State Bar, said having an open system like Oregon's and the immunity protection raised concerns about frivolous complaints being filed simply to attack an attorney's reputation.

But that hasn't been a problem, he said.

People are satisfied enough with the system, which has been around since the 1970s, that three years ago when some lawyers proposed changes to make it less open, the Oregon bar soundly defeated it, Sapiro said.

Oregon's system is different in ways besides the openness.

Lawyers in private practice are required to purchase malpractice insurance from the Oregon bar.

Oregon also requires practicing attorneys to take 45 hours of continuing legal education classes -- nine of which are ethics-related -- every three years, according to Sapiro.

People newly admitted to the bar must take 15 hours within the first year.

Hawaii has no such continuing education or malpractice requirements.

Many Hawaii lawyers in solo or small practices don't even have malpractice insurance, and they aren't required to disclose that to clients, lawyers say.

In the education arena, Hawaii last year began requiring new people joining the bar to take a professional-responsibility course that includes ethics training and how to run a practice.