[ MAUKA-MAKAI ]

|

Finding dignity He knows it. I know it. Writers make the worst interview subjects simply because they're too busy documenting others' lives to pay their own much heed, and when, or if, they should ever want their story made public (heaven forbid!), they feel most comfortable and qualified to tell it themselves, thank you very much.

in Everyman

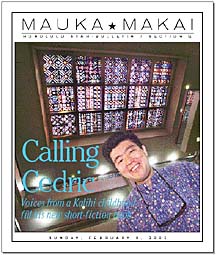

Cedric Yamanaka, a local TV

reporter, has made a second name

for himself for his short fiction

set in pool halls, bars and drive-insRecurring voices echo through poignant tales

By nadine kam

nkam@starbulletin.comThey also recognize the value of words -- how they have the power to conceal and reveal, inspire, sadden, teach, alter perceptions and, sometimes, change the world.

So already, Cedric Yamanaka, who says that the two things he's bad at are "talking about myself and talking about writing," is trying to take charge of his story, setting the scene: "Let's see, we sat in a Chinatown restaurant, and over a bowl of noodles, he said ..."

The man can't help it. He's got a dual writing career going. Those who keep up with local media know that he's a reporter for KITV. Those who keep up with the literary scene know he's an accomplished writer of short stories with a new compilation, "In Good Company," in bookstores, and he's also on the path to completing his first novel.

Although both careers involve writing, they are not as compatible as many would assume. While journalism calls for no-nonsense, "just the facts ma'am" statistics and logic, fiction calls for invention and fantasy. All going well, however, both should arrive at the truth.

The truth that Yamanaka -- who's not related to the other famous Hawaii author with the same surname -- has come up with after 38 years on this planet is that everyone deserves a little dignity.

He could fill his fiction with successful if somewhat uppity lawyers, eager and talented press interns and sage judges, courtrooms and corporate offices. Instead, his characters hang out in bars and billiard halls, work at drive-ins or don't work at all, or are students, fathers and sons who, though decent people, have nevertheless managed to disappoint or fail someone. His characters register as very real and, to middle-class society, very invisible.

"At a Bamboo Ridge workshop, a guy told me he doesn't read much but he reads my stuff. He said, 'You give a voice to a certain community in Hawaii that doesn't really have a voice,' and that made me so happy," Yamanaka said.

One reading celebrating pidgin presented by Bamboo Ridge Press, sponsored by Kumu Kahua Theatre and featuring bradajo (Jozuf Hadley), Lee Cataluna, Lisa Linn Kanae, Cedric Yamanaka and Da Pidgin Guerrilla Lee A. Tonouchi as emcee "4 Da Luv of Pidgin"

Where: Kumu Kahua Theatre, 46 Merchant St.

When: Starts at 7 p.m. tomorrow with pupu reception and music by Chris Planas; 7:30 p.m. reading

Cost: $15; free for Bamboo Ridge Press members

Call: 626-1481

"Over the years, growing up in Kalihi, I would hear all these stories, meet all these interesting people, and something inside me said I should write about these people, the ones washing their clothes, washing their cars, catching the bus. They have these incredible stories, but they don't go out and tell the world their stories.

"There's humor there, there's urban legend, love, hate, there's a dignity I saw, and that's what I try to slip in there. I think people underestimate the importance of themselves and their stories.

"Politicians, journalists, lawyers -- that might come later, after I've had time to digest it all," he said. "I'm still trying to digest stuff that happened to me 20 years ago."

Twenty years ago, Yamanaka was a newly minted Farrington High School graduate, complacent about his future. "I don't know why, but I never worried about making a living," he said. "I just didn't think about those things. I think it was my upbringing. We were poor, so I never had anything."

In high school he was the sports editor for the Farrington Governor, and continued flirting with journalism at the University of Hawaii-Manoa.

"I covered football for Ka Leo and got into the Aloha Stadium press box, and at one point I was in the restroom taking a leak next to Jim Leahey, thinking, 'He's the man! This is so cool!'"

Yet even in those moments when he felt he'd made it, sports reporting "still didn't feel like a calling."

Then, in 1985 a cousin saw a fiction contest advertised in a community newspaper, Ka Huliau, and encouraged him to enter.

Yamanaka wrote his first story, "The House at Alewa Heights," just for the contest. "I placed second and I was really encouraged. I think I won $10 or something. If not for the contest, I don't know if I ever would have attempted to write."

In all his stories the action flows gracefully. Yamanaka allows his characters' personalities and impulses fuel the plot, rather than dropping them into outlandish situations.

Along the way, "The Lemon Tree Billiard House," contained in this collection and anthologized frequently on the mainland, was made into a film produced by Dana Hankins and screened at the Hawai'i International Film Festival in 1996.

"I guess the writing found me," he said. "I never said I wanted to be a writer. I was a terrible student. During intermediate school at Kalakaua, essay contests were something we were forced to endure. I always would place but I never thought about it. I just did it because it was the assignment."

His second story, "What the Ironwood Whispered," also contained in "In Good Company," was published by the University of Hawaii journal Hawaii Review. The story is of a boy who is unfairly judged, and for whom low expectations become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Dispelling stereotypes continues to drive Yamanaka to write. "Everybody thinks they know you. They almost put limits on you by categorizing you. But 99 times out of 100, just when we think we know somebody, we find out we're wrong. There's more to the person hanging up clothes in the yard next to you and more to the person sitting in the cubicle next to yours.

"I've always thought of that. I hate to keep saying this because it sounds like a cliché, but growing up in Kalihi, we heard a lot about what we could and could not do; more often, it's about what we couldn't do.

"But I looked around, and I saw people who could have been potential doctors, lawyers and leaders. I didn't see losers. I saw people trying to find the way. Just by trying, that's half the battle.

"That's why appearances are not fact. The characters in 'Good Company' are fighting against that."

With a track record of published short stories, Yamanaka was advised to go to graduate school, and won a fellowship to attend Boston University. He had applied there to be "geographically and sociologically as far from Kalihi as I could get."

"At first I thought I'd bit off more than I can chew, the subzero winters and all. I'd be lying in bed thinking, 'Is there really a Farrington High School? Did that really happen?' It was such a surreal experience."

With the distance, voices of his local characters grew into a chorus that he couldn't get out of his head.

"I still think of some of those characters like I came up with them yesterday. I still think of Louis in 'Ironwood,' Mitch, Locust (the pool hustler and the hit man in 'The Lemon Tree Billiards House'), Mr. Kaahunui (the former wrestler in 'The Day Mr. Kaahunui Rebuilt My Old Man's Fence'), Shiela (the pretty tennis champ whose life revolves around obligations in 'The Three-and-a-Half-Hour Christmas Party')."

There's enough ambiguity in the stories so that readers, too, are left haunted by the characters, wondering what happened to them, especially Kelly Ahuna, who lived in the evil house in the Mr. Kaahunui story.

"Everybody asks about Kelly. They say, 'Just between you and me, what happened to the girl in the house?'

"I kind of know, but I didn't want it to be black and white, just like evil isn't black and white. I want readers to think and draw their own conclusions."

In Boston, participation in writers groups was a requirement, and he found himself in the company of other fledgling writers like Arthur Golden, who went on to write "Memoirs of a Geisha."

Yamanaka found the process of being critiqued wasn't scary at all, although he confesses that his classmates might have gone easy on him.

"I think they pitied me because I'd wear these threadbare jackets. They said, 'You're gonna die. Get yourself some real gloves and a winter coat.' I'm like, 'What? I got this from Liberty House, and it has to last me the year.'

"They made all my stories better, although they had a lot of problems with pidgin." To this day, Yamanaka never uses the dialect gratuitously. "I understood where they were coming from. It's hard enough to get people interested in reading, and when they see all those words, that just makes it harder."

In Boston, Yamanaka's professors called him "a natural writer."

"The only way I can describe it is that some people are born to throw a football 70 yards, and some people are born to write symphonies at age 2. Writing is the only gift God gave me."

As a result, his work habits would exasperate anyone who teaches the craft as a series of techniques and rules.

"I never tried to think too much about it. I have no set regimen, whether it's writing in the afternoon or when I come home from work. When it happens, it happens."

Yamanaka said the most difficult aspect about releasing the collection was coming up with its title.

"But when I read them through, I realized each common thread was that lives were enhanced by the appearance of another person.

"I think about what would have happened to me if I never got that fellowship, if I hadn't been encouraged to write."

He had come back from Boston with no prospects, and after applying to several media organizations, received only one response, from KHVH's Don Rockwell. He worked as a radio reporter for a year before making the jump to television.

"Writing has changed my life. It's given me an education. It's given me a job. It's given me a new way of looking at the world," he said. "I think I'm more tolerant about things because of writing, so if people are cutting me off on the freeway, blasting their horn at me, I gotta look beyond that, like, maybe that person had a bad day.

"Everyone deserves respect, even though sometimes it's harder to see in some than others. Writing has taught me that everyone has something to offer, everyone has something to say."

Click for online

calendars and events.