Hawaiian language It was 1983 when a small group of Hawaiian-speaking educators embarked on an effort to save their native language.

makes gains but

still in danger

It is one of thousands of

languages experts say could

die by the end of the centuryBy B.J. Reyes

breyes@starbulletin.comSince then the group known as Aha Punana Leo has seen the language make a significant comeback.

Today, some 7,000 to 10,000 Hawaiians currently speak their native tongue. That is up from fewer than 1,000 in 1983, said Luahiwa Namahoe, a spokeswoman for Aha Punana Leo.

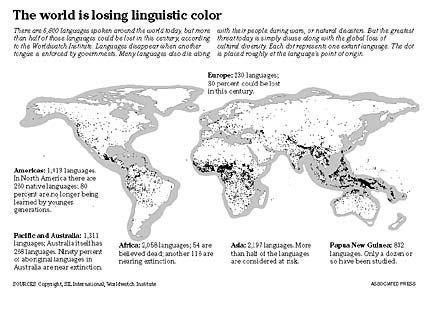

But the group's work is not over, Namahoe said, particularly in light of a report that says half to 90 percent of the world's 6,800 languages could be extinct by the end of the century.

"I do know that the state of Hawaii is the only one of the 50 that holds the status of two official languages," Namahoe said. "Unfortunately, there are a lot of people out there with sadder histories than us, sadder realities than us."

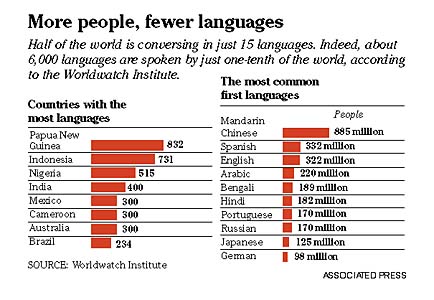

Languages need more than 100,000 speakers to pass from generation to generation, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO.Today, half of all languages are spoken by fewer than 2,500 people each, according to the Worldwatch Institute, a private organization that monitors global trends. War, genocide, fatal natural disasters, government bans and the adoption of more dominant languages also contribute to the demise.

Linguists estimate that 3,400 to 6,120 languages could die out by 2100, a statistic more dour than the widely used estimate of one language dying off every two weeks.

Among Hawaii's immigrant population there has always been a large diversity of languages.

"In Hawaii, I believe that the language that's most endangered, ironically, is our own language," Namahoe said.

The language nearly became extinct when the United States banned schools from teaching students in Hawaiian after annexing the then-independent country in 1898.

Aha Punana Leo, which means "language nest," opened Hawaiian-language immersion preschools in 1984, followed by secondary schools that produced their first graduates, taught entirely in Hawaiian, in 1999.

Native Hawaiian is not the only language of concern to people in Hawaii.For more than a decade, University of Hawaii public health professor Faye Untalan has staged an effort to keep alive Chamorro, the native language of Guam and the rest of the Mariana Islands.

Fearing that the language could die out in 30 years or so, she has taught Chamorro to small groups of UH students through informal, independent-study courses.

Her efforts recently got a boost when the university approved her request to offer Chamorro 101, the first such college-level class to be taught outside of Guam, in the fall semester.

Similar revival efforts have been undertaken in other parts of the world facing the loss of indigenous languages.

Namahoe appreciates the efforts taken by Hawaiians, natives and transplants in keeping the indigenous language alive.

"A lot of people, regardless of who their ancestors are, are doing a lot ... to perpetuate the language of a culture," she said. "They love Hawaii, too."

Still, she realizes that now is no time to get complacent.

"When this language is back in its place in the government, in the schools, in the churches, in the huis and in society, then I think we'll all breath a little easier," she said.

The Worldwatch report, "Last Words: The Dying of Languages," appears in the May/June issue of the organization's magazine.