Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

By Gregg K. Kakesako

Star-Bulletin

Did Cmdr. Scott Waddle increase or minimize risks that led to the collision between his nuclear submarine and a Japanese fishing trawler nearly a month ago, resulting in the death of nine people?

Harsh questions

What happened?

Investigator suggestions

That was the underlying question raised this morning by Rear Adm. David Stone on the fourth day of a rare court of inquiry looking into the Feb. 9 sinking of the Ehime Maru nine miles south of Diamond Head.

Stone, one of three admirals investigating the accident, said he still hasn't made up his mind if Waddle, the skipper of the Greeneville, should be held responsible for the accident.

But his questions were the harshest criticism yet of Waddle's actions.

Despite statements by Waddle's attorney yesterday that Waddle's emphasis since taking command of the Greeneville in March 1999 has been "safety, efficiency and backup," Stone said, "these themes are just words unless translated into action." He also seemed to refute statements by Waddle's attorney, Charles Gittins, yesterday that Waddle exercised his "best judgment."

Stone said his interpretation of "best judgment" means actions conducted that are safe, prudent and correct.

When asked to comment on Waddle's actions, Rear Adm. Charles Griffiths, who conducted the preliminary investigation into the Feb. 9 accident, said Waddle is a qualified and experienced commander.

Griffiths said Waddle went through the steps, but he failed because he didn't go far enough. "He had a bad day where some mistakes were made," he said.

Griffiths said Waddle didn't make any single mistake, but "I see a number of things that fall short of what you want your goal to be ... ending up in a collision."

Also at this morning's session of the inquiry in a Pearl Harbor courtroom, a Navy attorney for Lt. (j.g.) Michael Coen got Griffiths to acknowledge that Waddle had a better opportunity to evaluate the surface of the sea through the periscope than Coen before the accident occurred.

Asked about Coen's performance on the Greeneville, Griffiths testified that he was "a very deliberate" junior officer.

"The criticism is that if you need to get things done in a hurry, he was one of the worst," Griffiths said, "but his strength is that he will do every step."

Under cross-examination by Coen's attorney, Lt. Cmdr. Brent Filbert, Griffiths acknowledged that Fire Control Technician of the Watch Patrick Seacrest should have warned either Coen, who was Greeneville's officer of the deck and in charge of ship's operations at the time of the accident, or Waddle of a sonar contact, indicating a vessel.

This was before the Greeneville was ordered to periscope depth of 60 feet. At that point, Seacrest had information that the Ehime Maru was at 5,000 yards and closing.

"If the officer of the deck or the CO (commanding officer) had this information while ascending or at periscope depth, could they have taken action?" Filbert asked Griffiths.

Seacrest, 34, said what happened on the day of the collision is much more complicated than what has been reported. Both Griffiths' and the National Transportation Safety Board's investigations have said that Seacrest said he wasn't able to do his job because the 16 civilians in the control room were in his way. Seacrest has not been named as a party in the court of inquiry or as a witness.

In this morning's proceedings, Greeneville defense attorneys began an assault on the Navy preliminary investigator's report that crew of the submarine were too busy entertaining civilian guests and rushed procedures, which led to the sinking of the Ehime Maru and the loss of nine men and boys on the training vessel.The Navy court of inquiry is considering the actions of three Greeneville officers: Waddle; Coen and Lt. Cmdr. Gerald Pfeifer, the executive officer and second in command on the sub.

Pfeifer's military attorney, Lt. Cmdr. Timothy Stone, tried to point to inconsistencies in Griffiths' report, trying to dispel Griffiths' findings that Pfeifer failed to be a "forceful back up" to his boss.

Yesterday, Gittins tried to convince the court that Griffiths' investigation into the accident was incomplete and inaccurate.

Both Gittins and Stone in their questioning of Griffiths pushed hard on the fact that Griffiths had to rely on the interviews of others since Griffiths was never able to personally talk to Coen, Waddle and Pfeifer.

Pfeifer, during one of the breaks in the proceedings yesterday, went outside and approached the relatives of missing Japanese to apologize. "I'm sorry for your loss," he said to Kazuyo and Mikie Nakata, whose son is one of the missing.

On Tuesday, Griffiths had testified that Capt. Robert Brandhuber, the No. 2 man in the Pacific Fleet Submarine Force, believed Waddle was moving "too quick" through normal procedures such as the time spent on analyzing sonar data and periscope checks for vessels before surface.

Under cross-examination yesterday, Griffiths amended his statement, saying "too quick" may have been an improper way Brandhuber characterized it.

Gittins also got Griffiths to acknowledge that a crucial fire-control technician knew the Ehime Maru was close, but never told Waddle.

Waddle and Coen have requested "testimonial immunity," a common practice by defendants, so their testimony before the court cannot be used against them.

Adm. Thomas Fargo, Pacific Fleet commander, ordered the creation of the court of inquiry and will decide whether criminal charges will be imposed.

But even if Waddle is not granted immunity, Gittins said that he might still testify because he wants to tell his story.

Under questioning Griffiths acknowledged that Waddle, 41, was an officer never known to "cut corners" before the Ehime Maru accident. He also acknowledged under cross-examination that Waddle was willing to return late to Pearl Harbor after a daylong cruise.

"My logical connection to being generally behind schedule and trying to catch up was my assumption," Griffiths said. "Maybe that's not the case."

It will be up to the panel of three admirals to determine whether any of the three Greenville officers or other crewmen will face charges of negligence or dereliction of duty. The court also has been asked to determine whether Navy's policy to allow civilians to participate should continue.

Hisao Onishi, the Ehime Maru, is expected to be called to the witness stand next week.

So asked Vice Adm. John Nathman yesterday, overseeing the military's court of inquiry into the USS Greeneville-Ehime Maru collision. 'WHAT WENT WRONG?'

Five main factors probably contributed, responded Rear Adm. Charles Griffiths Jr., the Navy officer who did the initial investigation into the Feb. 9 collision. Those factors:

A rush to complete an emergency surfacing drill

A lack of qualified sonar operators

Broken equipment that could have helped detect the Japanese ship

The number and location of 16 civilian visitors aboard the USS Greeneville

A command climate wherein crew members were unaccustomed to questioning the commanding officer because they trusted his skills

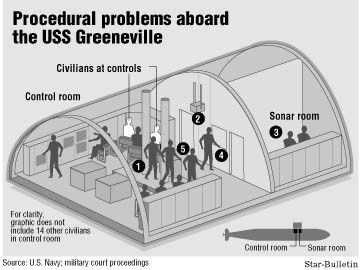

According to testimony from Rear Adm. Charles Griffiths, these are some of the procedural problems aboard the submarine before it collided with the Ehime Maru. Procedural problems aboard

the USS Greeneville

1. The emergency surfacing drill was performed 45 minutes behind schedule because lunch with civilian guests ran long, partly because Cmdr. Scott Waddle was chatting with the visitors. The lateness apparently prompted Waddle to rush through preparations for the surfacing drill. Waddle ordered his crew to get to periscope depth in five minutes, despite procedures that require 10 to 15 minutes to prepare. At periscope depth (60 feet), the crew spent 80 seconds scanning the horizon with its periscope, rather than the prescribed three minutes.

2. A sonar display that allows the commander and the officer of the deck to monitor surface vessels from the control room was inoperable.

3. A sonar supervisor who was supposed to be monitoring a trainee in the sonar room spent much of his time serving as a guide for the guests.

4. The fire control technician, who plots the surface vessels detected by sonar, had data showing the Japanese boat was as close as 2,500 yards from the submarine as it went to periscope depth. However, he didn't tell the commander or the officer of the deck because civilians were standing between him and the officers. The fire control technician also failed to maintain a manual plotting of surface vessel bearings, as required.

5. The ship's executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. Gerald Pfeifer, and a senior officer who accompanied the civilians aboard, Capt. Robert Brandhuber, both told investigators they felt Waddle was rushing preparations for the emergency surfacing drill, but neither spoke up.