Hawaii land

the source of power,

the pot of gold

at rainbow’s end

At the time of statehood,

By Richard Borreca

ownership was concentrated,

with fewer than 100 owners

holding half of all the land

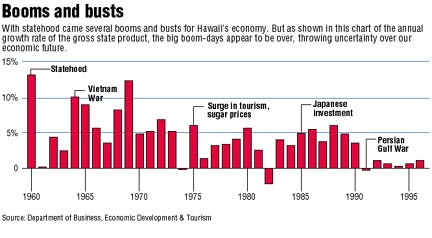

Star-BulletinHawaii's dream and nightmare dovetailed into one: develop the land, make every parcel as valuable as possible.

"Ten years from now I envision Honolulu to be largely concrete and steel, with some coconut trees sprinkled throughout," boasted Lowell Dillingham, developer of the Ala Moana Center, in 1961.

"This is inevitable as the Islands swell in population to perhaps 900,000," continued Dillingham. While his concrete and steel prediction has not come true, more than 1.1 million now live in Hawaii.

Dillingham, son of magnate Walter F. Dillingham, looked at Hawaii from an amazing perch: his Ala Moana Center had doubled in size in 1961 and retail sales there accounted for a full 5 percent of all sales in the new state.

While commercial real estate was valuable, it was the tourism boom that echoed through the new high-rise canyons of Waikiki. Jumbo hotels - built to match the lumbering jumbo jets which began coming regularly in 1970.

Between 1968 and 1971, 17,140 hotel rooms were created in Waikiki, doubling the state's hotel inventory.

The Kalakaua Avenue view of Diamond Head was first blocked by the 1970 Holiday Inn, with its 650 rooms rising 25 stories high. Today, the hotel is called the Hawaiian Waikiki Beach Hotel.

But perhaps the building boom's crescendo sounded in 1974, when young developer Chris Hemmeter blew up the Biltmore Hotel to build the first super-block, the Hemmeter Center and the adjacent King's Alley. The hotel was the Hyatt Regency, with its semi-indoor waterfall setting the stage for lavish, vaguely tropical Hawaiian resorts.Finally, in 1976, the city slammed the brakes on Waikiki development by imposing a special design district for the overbuilt, underplanned area, said Mary McDonald, University of Hawaii associate professor of geography.

Land ownership at statehood, meanwhile, resembled most of "Central America with a few landlords controlling most of the land," according to Gary Fuller, UH Population Studies Department director.

When Hawaii became a state, planner Tom Creighton noted, four estates owned one-third of Oahu; fewer than 100 owners held half of all Hawaii's land; and the state and federal governments controlled 40 percent of all acreage.

The Legislature, under the Democrats, was determined to break up the sugar plantations' control of vast tracts of agricultural lands. By and large, however, the land was kept in the hands of large holders -- mostly, the Bishop Estate -- which dribbled parcels out for high-priced housing development.

Key to land values was the leasehold system, in which the landowner kept title to the property in anticipation that values would have soared when the lease was later renegotiated.

That has dramatically changed in the last 15 years, however, as leasehold reform allowed families to buy both their homes and the land under them, Fuller said.

The reform measures forced landowners to convert their property to fee simple at a negotiated price. The large estates, particularly Bishop Estate, were forced to sell their lands in exchange for hundreds of millions of dollars.

"Land is limited in an island community, and control of it generally means more than in a continental situation," Fuller explained.

Though Bishop Estate was compelled to sell some of its 341,545 acres, the resulting bonanza fueled its purchase of shopping malls - first here and then across the mainland. The estate also bought golf courses, vast tracts of timber land and significant stakes in investment firms.

Finally, the rich Hawaiian soil was growing a new kind of wealth. The mixture of political power, development clout and limited buildable land meant there were fortunes to be made by those dabbling in both politics and real estate.

As Gavan Daws and George Cooper wrote in "Land and Power in Hawaii," the story of Democratic power over the last 30 years here has been the struggle for the land.

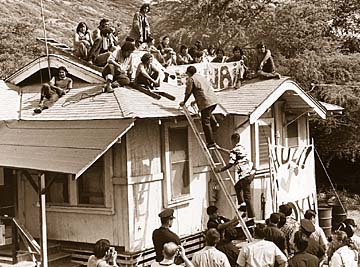

Sometimes the reformers were on the front lines, such as the protests against development of Kalama Valley and the successful preservation of Waiahole and Waikane valleys. But other times, the devil was in the land deals done by the former Democratic revolutionaries.

"In Democratic years," Daws and Cooper wrote, "political power gained at the polls meant a chance to lay hold of that land power, reach out and manipulate land, buy title to large tracts, control the development rights to even larger acreage -- and profit from it."

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin is counting down to year 2000 with this special series. Each installment will chronicle important eras in Hawaii's history, featuring a timeline of that particular period. Next installment: November 8. About this Series

Series Archive

Project Editor: Lucy Young-Oda

Chief Photographer:Dean Sensui