EPILEPSY

Surgical solutions

'When you look at what Trevor

has been through and how far

he's come, his courage

is inspiring'By Christine Donnelly

ABOUT EPILEPSY

ABERCROMBIE ROAST WILL HELP

SUPPORT GROUP

Star-BulletinTREVOR Bierwert's seizures were so frequent, so disabling, they led his mother and father to a desperate prayer: Please, let doctors be able to remove nearly half his brain.

"At the beginning we were hoping they could control (his epilepsy) with medication, then the special diet. At first about the surgery, you're like, "No way!' But by the end you're praying, "Please, please,'" recalled his mother, Sheila Bierwert of Hawaii Kai. "It's such a long process; your hopes are shot so many times. By the time you get there, nothing else has worked."

His parents recounted their first-born child's ordeal matter-of-factly and without self-pity, hoping to educate people about epilepsy, which is characterized by excessive electrical impulses in the brain that cause recurrent seizures. Trevor is one of about 13,000 people in Hawaii who have it, although his drug-resistant case was unusually severe, and the partial-hemispherectomy surgery he had to correct it is even rarer.

"There's no way Trevor could have come as far as he has without the support of a lot of people. We got information and help from all over. Now we'd like to share some," his 31-year-old mother said. "Plus, we'd like to promote compassion and understanding."Born Nov. 11, 1992, Trevor seemed to develop normally until he was nearly 4. Then his parents noticed he sometimes made a momentary lurching movement, hunching his back and arching his arms. A pediatric neurologist confirmed Trevor had epilepsy in November 1996. The root cause was unknown, as in about 70 percent of all cases, according to the Epilepsy Foundation of America.

Doctors prescribed anti-seizure medications at increasingly high doses, but no combination worked well. At one point, Trevor's dose of Dilantin was so high that "he was toxic, throwing up all the time. He couldn't walk. It was devastating," Sheila Bierwert recalled.

Hawaii at that time lacked the specialized care Trevor needed, so when his father, Dave, also 31, was offered a job in Michigan in the summer of 1997, the family moved, buoyed by the prospect of more medical options for Trevor, who was getting worse.

The fleeting and sporadic lurches had intensified to "atonic drop seizures" that knocked Trevor to the ground without warning up to 100 times a day, forcing him to wear a helmet to guard against head injury. The carefree boy who had once loved to sing and put together puzzles was now both heavily medicated and continually seizing, leaving him unable to concentrate or learn anything new. In fact, "he was losing the things he had known," said his father.

Discouraging diet, tests

The Michigan medical team tried new drugs, in different combinations, but with similarly dismaying results. Next Trevor tried the Ketogenic Diet, a high-fat, low-carbohydrate meal plan that had reduced seizures in some children not helped by medication. But after about two months of meals such as hot dogs dipped in mayonnaise and omelets made with whole cream, cheese and extra butter in the pan, the young boy still had 50 or so seizures upon waking in the morning, his parents said.The Bierwerts stopped the diet and began researching surgical options they had heard of but not considered earlier as they tried less invasive treatments. They recalled having seen a doctor on TV explaining how seizures sometimes could be eliminated by removing the part of the brain where they originate. The surgery works best on young children because at that age the remaining brain tissue more readily assumes the functions of the part that's removed.

(There are several types of brain surgery for epilepsy, with hemispherectomies the rarest. Only about 20 to 30 are done in the United States each year, mainland specialists estimated. The operation has not been done in Hawaii, according to leading neurosurgeons here.)

The Bierwerts e-mailed the doctor, pediatric neurologist Harry Chugani of Children's Hospital of Michigan at Wayne State University in Detroit, and in June 1998 he agreed to see Trevor. The consultation brought a new round of brain scans, hospital stays and bad news.Trevor's brain had abnormalities on both sides, while surgery works best when one side is clear. Chugani and the other medical specialists on the team did not give up, however, hospitalizing Trevor for around-the-clock monitoring to see if they could pinpoint where the seizures originated. The ideal is to find a precise focal point and remove the least amount of brain tissue necessary. The monitoring was followed by two more brain scans, but the judgment remained that Trevor was not a good candidate, his parents recalled.

Still, the doctors persevered, presenting the case at a weekly surgical consultation. There, another colleague noted that although there was not an obvious focal point, each time Trevor had a seizure, his body fell to the left, meaning the seizures originated somewhere on the right. In late 1998 the team decided Trevor could have surgery.

"It was right before Christmas and we were so excited. It felt like a new beginning," Sheila Bierwert said.

Success, it seems, at last

Trevor was admitted to the hospital on April 13, 1999, his healthy sister Emma's second birthday. Doctors opened his skull and placed a flat grid of 106 electrodes on the right side of his brain, closed him up and monitored the bedridden boy's seizures for seven days, deciding where to operate.On April 20, 1999, they removed 75 percent of the right side of Trevor's brain, leaving the motor and sensory cortex of that side as well as the entire left side intact. The hope was that the seizures would cease immediately and that the left side of the brain -- which controls such functions as language and fine motor skills -- would progressively take over the functions of the right, which controls visual orientation as well as gross motor skills for the left side of the body.

"After the surgery, we were finally able to see him in ICU, and we walk in and he was seizing! His whole left side was just twitching. We were devastated," Sheila Bierwert said. "It was not what we expected at all," added Dave Bierwert.

But with medication the seizures stopped four days later. And although he had to return to the hospital to have a permanent shunt inserted to drain excess fluid (which fills the cavity where the brain tissue used to be), Trevor has not had a seizure in more than six months."Saturday, April 24, 1999, at 12:10 p.m. to be exact. Some things you just don't forget," Dave Bierwert said.

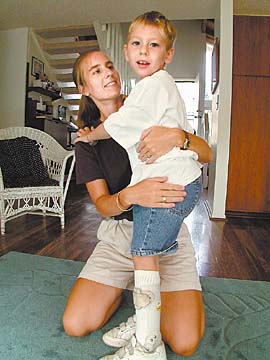

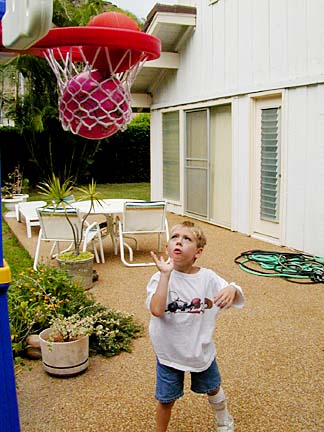

Trevor was paralyzed on the left side after the surgery but was walking again within two months, and now runs and shoots baskets, despite the brace on his left leg. Intellectual progress has been slower but also steady. He can once again complete puzzles, understand directions and pay attention better, his parents said. He's learning to talk, adding new words near daily. And being seizure-free means no more helmet.

"The whole point of the surgery was to give him that chance, to develop and grow," said Dave Bierwert. "The seizures were so bad, they prevented him from learning."

'Push hard, hope for the best'

Confident their son was on the mend, the Bierwerts moved back to Honolulu this September to be closer to Sheila's family. Dave is looking for work in financial management, while Sheila, a former schoolteacher, is a stay-at-home mom.Trevor attends kindergarten at Kamiloiki Elementary School, where he gets occupational, physical and speech therapies as a special-education student and also spends part of each day with the regular class.

His parents sent a letter to all his classmates explaining his situation, and have been thrilled by their support.

No one can say how much more Trevor will progress, or guarantee he'll never have another seizure.

"Sometimes these kids turn out to be normal, and others show a mild delay but are much better off than before. Time will tell. We like to push them hard and hope for the best," Chugani, the pediatric neurologist from Detroit, wrote in an e-mail response to questions.

Trevor himself has the inquisitive eyes and easy smile of a happy soul. It's hard to tell how much he understands of his journey, but there's no mistaking the grit it took to withstand the pain. To his family he's a hero.

"Not many people admire 7-year-olds. But I really have a lot of admiration for Trevor," said his aunt Susan Hamilton, an English teacher at Leeward Community College. "When you look at what he's been through and how far he's come, his courage is inspiring."

Here are some facts and figures about epilepsy: ABOUT EPILEPSY

Definition: Epilepsy is a generic term to describe recurrent seizures that vary in frequency and severity. Seizures result from excessive electrical activity in the brain, as nerve cells fire impulses wildly and uncontrollably. This might appear as convulsions in one person with epilepsy, and a distortion of the senses, fixed staring or loss of movement in another.

Numbers: Some 13,000 people in Hawaii have epilepsy, including more than 4,000 children.

Treatment: Seventy percent of patients can limit seizures using medication alone; some 20 anti-epileptic drugs are on the market. Brain surgery is sometimes an option if medication fails, and usually involves removing only a small amount of brain tissue. Hemispherectomy, or removing half the brain, is the most radical of the several surgical options. Vagus Nerve Stimulation, using an implanted device described as like a "pacemaker for the brain," is also available to help control seizures, as is the high-fat Ketogenic Diet.

Causes: The cause is undetermined in about 70 percent of cases. Among the remaining 30 percent, the most common causes of recurrent seizures include head injuries, brain tumors, stroke and infections such as meningitis and viral encephalitis.

Mortality: Although most seizures are benign, prolonged episodes can lead to a condition that causes brain damage and even death. People with epilepsy also have a higher-than-average fatality rate for sudden unexplained death syndrome and accidental death, especially drowning.

More information: Call the Hawaii Epilepsy Center, which since January 1999 has specialized in treating difficult cases, at 547-6944 or via the Internet at http://www.hawaiiepilepsy.com. Information about support groups and other services to families can be had by calling the Epilepsy Foundation of Hawaii at 951-7705.

Sources: Hawaii Epilepsy Center, Epilepsy Foundation of America, Epilepsy Foundation of Hawaii, The Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives.

Abercrombie roast will

By Christine Donnelly

help fight the affliction

Star-BulletinHoping to shed light on an affliction he says has long been misunderstood, Hawaii Rep. Neil Abercrombie will take the hot seat in public to raise money for the Epilepsy Foundation of Hawaii.

"It's something that is essentially hidden. People with epilepsy are almost modern-day Hansen's Disease patients ... with a very low degree of public awareness and a lot of myths," said Abercrombie, whose own symptoms have improved so much that he no longer requires medication. "If me getting roasted can raise money and awareness, then I'm all for it."

Saturday's event, which is open to the public, starts at 5:30 p.m. at the Hawaii Prince Hotel in Waikiki. Tickets are $100 each, $60 of which is tax deductible.

Included are pupus, cocktails, live music and a silent auction, along with the roasting of the longtime Democratic congressman by such scheduled guests as Gov. Ben Cayetano, Mayor Jeremy Harris, U.S. Rep. Patsy Mink and KSSK radio personality Larry Price.

To purchase tickets, leave a message at the Epilepsy Foundation of Hawaii at 951-7705 or call Ed Kemper at 524-0330, ext. 2; Warren Fabro at 523-5900; or Alan Stein at 547-6944.

Abercrombie's epilepsy, which developed in 1964 when he was 26, was characterized by severe headaches and, while he slept, seizures he mistook for nightmares. Doctors could not say for sure what caused it, but suspected he caught a viral infection swimming in the ocean.

He took prescribed medication as well as vitamins he hoped would reduce scar tissue in the brain. His doctors correctly predicted that the symptoms would fade over time, and he took his last dose of the anti-seizure drug Dilantin in 1986.

"I've been medication-free since then with no serious seizures, so I've been very lucky," Abercrombie said. "But that's the nature of epilepsy; some people who have it can lead completely normal lives and others face serious obstacles."

Abercrombie said the disorder motivated him "all the time, every day. But it never stopped me."

"I never felt I was disabled, but I was challenged," he said. "That's one of the reason I feel so strongly about never labeling anybody because invariably it means you're trying to limit someone from making the contribution that they can."

The Bierwerts hope to start a Honolulu support group for parents of children with any degree of epilepsy. SUPPORT GROUP IN THE WORKS

Existing groups focus on adults who have epilepsy themselves, "but I'd like to meet other parents who are helping young kids through this," said Sheila Bierwert.

Anyone interested can e-mail the Bierwerts at sbierwert@hotmail.com. And they have a Web site telling Trevor's story at http://www.geocities.com/HotSprings/ Chalet/1127/.

Christine Donnelly, Star-Bulletin