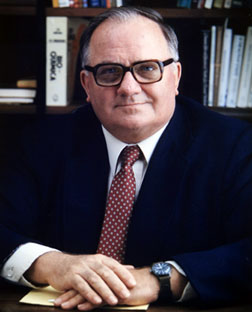

DR. TERENCE A. ROGERS /

JOHN A. BURNS SCHOOL

OF MEDICINE FOUNDER

UH dean opened medical field to minorities

Dr. Terence A. Rogers, 83, who founded the John A. Burns School of Medicine with a concept of enabling nontraditional and disadvantaged students to pursue medical careers, died Wednesday at Kuakini Medical Center.

COURTESY PHOTO

Dr. Terence A. Rogers received a "Living Treasures of Hawaii" award last year from the Honpa Hongwanji Mission for dedicating his career to improving health in Hawaii and the Pacific islands.

|

|

He used to smile and say he had "engineered a medical social revolution in the middle of the Pacific," said Dr. Patricia Blanchette, medical school professor and chairwoman of geriatrics. "He was extremely pleased."

Rogers received a "Living Treasures of Hawaii" award last year from the Honpa Hongwanji Mission for dedicating his career to improving health in Hawaii and the Pacific islands.

He was born in England and trained in nutrition and physiology. He was an undergraduate student at the University of British Columbia and did graduate work at the University of California. He taught at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Stanford University.

Rogers was a young naval officer in World War II and an aide to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, helping to analyze critical data to guide troops in landings during the Normandy invasion, according to a biographical sketch by his longtime friend and colleague Dr. Benjamin Young, former dean of students at the University of Hawaii medical school.

Young said Rogers "had a prodigious memory and possessed an extraordinary grasp and depth in multiple fields of human knowledge." He also was noted for his "quick humor."

Rogers was a chief researcher in NASA's early days, studying effects of gravitational forces and space travel on humans, and was part of an experimental team with America's first astronauts -- John Glenn, Alan Shepherd and Virgil Grissom.

He came to Hawaii in 1964 and became involved in developing UH's Pacific Biomedical Research Center, Young said.

He recruited Dr. Windsor Cutting from Stanford as director of the research center and formed a two-year school of medicine with Cutting as the first dean. It opened to students in 1967 and developed into a four-year program in 1973 under Rogers' leadership. He became dean in 1972, retiring in 1988.

"Terry Rogers was not born in the islands, but he was truly a son of Hawaii and the Pacific," said U.S. Sen. Daniel Inouye. Rogers' "vision went beyond simply educating a corps of skilled medical professionals," he added. "It meant having those professionals committed to the delivery of first-class health care and striving to improve all aspects of community life.

"Terry's legacy is seen in the higher number of native Hawaiians in medicine and in the rigorous Burns School of Medicine programs that have led to improved health-care services in American Samoa, Palau, Micronesia and the Marshall Islands," Inouye said.

Social activist Ah Quon McElrath, whose interests in health care led to a long friendship with Rogers, said Rogers was able to put together a medical school with the late Patricia Putnam and others without building a hospital. He felt students could get a better idea of cases they would be treating if they were in community hospitals, she said. "We owe him a lot for placing the medical school in a unique situation in the middle of the Pacific."

Young, the first native Hawaiian to be board-certified in psychiatry, said Rogers tapped him in 1972 to start what became the Imi Ho'ola program to get more Hawaiians and Pacific islanders into medicine.

He said the program "saw the numbers of Hawaiian, Filipino, Micronesian and Samoan M.D. graduates increase to logarithmic proportions." There were fewer than 10 licensed Hawaiian physicians in the state in 1972, and now there are more than 300, Young said.

"Thus, our medical school became an instrument not only for training physicians, but also for social change," he said.

Blanchette said she was a student at the medical school when Rogers was dean, and he recruited her to the faculty when she completed a fellowship at Harvard University. They had talked about starting a geriatric program when she was in the fourth graduating class in 1979, she said. "He told me to come back to Hawaii and start the program I kept telling him we should have."

She said Rogers "railed against discrimination" and did everything he could to open the medical school and the profession to those for whom it was previously impossible.

"He was one of the greatest feminists I've ever met," she said. When she was a student and some volunteer faculty members made inappropriate sexist remarks, she said, "Terry personally put his foot down and said he wouldn't welcome them if they couldn't learn times were changing and it was inappropriate."

When Rogers retired from UH, he became superintendent of Hawaii State Hospital to try to straighten out some problems with new buildings that did not meet mental-hospital specifications, Blanchette said. "He was always good at problem-solving. He found funds to remodel the brand-new buildings to psychiatric specifications."

Survivors include Rogers' companion, Tomi Satake Haehnien of Hawaii Kai; children Valerie Rogers, Clare Rundall and Keith Rogers, all of Canada, and Patrick Rogers of Paris; and two grandchildren.

Memorial services are pending. Rogers willed his body to the medical school.