GARY T. KUBOTA / GKUBOTA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Halona Tanner, left, and Keali'i Roldan use way-finding skills to chart a sailing course from Hawaii to Tahiti during a recent seminar in Hilo.

|

|

Route to knowledge

A seminar is passing on traditional way-finding methods to future generations

HILO » Using a Hawaiian star chart, Halona Tanner leaned over a map of the Pacific Ocean and tentatively drew a line for a navigational course from the Big Island southward toward Tahiti.

"I think we're a bit off," said Tanner, checking his plotting with his partners.

Tanner, 33, of the Big Island, was one of more than 130 people in Hawaiian sail voyaging groups statewide participating in a seminar that taught native way-finding skills.

The course, called Imi Naauao 2008, is an attempt to merge modern teaching strategies to impart traditional way-finding knowledge to people voyaging on double-hulled sailing canoes.

The course, called Imi Naauao 2008, is an attempt to merge modern teaching strategies to impart traditional way-finding knowledge to people voyaging on double-hulled sailing canoes.

Without Western tools such as a sextant and chronometer, modern way-finders are using native knowledge of nature including the stars, winds and currents to navigate their way to Pacific islands.

The seminar, sponsored by several organizations including Matson Navigation and the Alexander & Baldwin Foundation, took place Saturday at the University of Hawaii-Hilo's Imiloa Astronomy Center.

The crews were to receive lessons in Hawaiian crafts and knot tying yesterday, followed by a sail on small double-hulled canoes today.

Chad Baybayan, a native Hawaiian way-finder and principal organizer, said the intent is to give voyagers a quicker route to knowledge and a deeper understanding of their Hawaiian history.

The seminar was also an opportunity for voyaging societies to share way-finding information.

Currently, four deep-sea voyaging canoes are operating in Hawaii, and three are being built or refurbished.

"This is a collaboration of the way-finding community," Baybayan said.

Baybayan said islanders traditionally learned native way-finding by watching while aboard a voyaging canoe.

He said it took him 30 years and several voyages to feel comfortable enough to be a navigator on a voyage.

Baybayan said attendance of the event has tripled since its start last year, indicating an increasing interest in Hawaiian voyaging and navigation.

Most of the male and female participants were in their 20s and 30s, representing the next generation of native voyagers and potential way-finders.

The crew members might also be among the future voyagers in an around-the-world journey being discussed by the Polynesian Voyaging Society, perhaps by 2011.

Society president Nainoa Thompson said he was encouraged by the turnout.

"This room is powerful," Thompson told the group.

Thompson said the society was still discussing the idea of an around-the-world voyage, and it would only be possible if young voyagers were behind it.

"This won't go if young people don't come," he said.

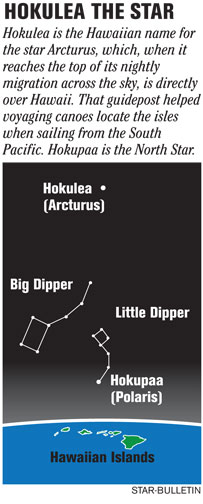

Besides receiving a talk from Thompson about the revival of Hawaiian way-finding more than 30 years ago, crew members studied Hawaiian star charts and navigational canoe charts.

Baybayan said in plotting courses and deciding when and where to sail, navigators have to account for seasonal storm patterns in different quadrants and find the safest period for sailing.

Crews plotting courses had to calculate a 12-mile-a-day current drift from east to west in one quadrant and no drift in another.

They also learned to use their fingers to determine the number of degrees the Southern Cross stars should be above the horizon if they were nearing the Big Island.

A seminar packet included maps and chants to help them remember lines of stars.

Tanner, a clinical psychologist who has been on interisland sail voyages, said the seminar allows a lot of information about way-finding to be passed on to future voyagers.

"It makes a lot of sense," he said. "It's key for increasing accessibility and expansion of voyaging."