CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

A Sandy Beach bodyboarder, at top, goes upside down as he maneuvers down wave.

|

|

Hapuna Beach leads the state in spinal-cord injuries

The Big Island beach leads isle spots for injuries that can prove debilitating even with only mild wave sizes

STORY SUMMARY »

For years, Sandy Beach's unforgiving shore break has been known for broken necks and backs.

But the popular Oahu bodysurfing spot ranks only third among Hawaii beaches that saw the most spinal cord injuries in a six-year period ending in 2006.

Topping the list is Hapuna Beach on the Big Island, with 11 cases, followed by Waikiki, which had eight, according to data compiled by the Queen's Medical Center since 2001. Sandy's had seven incidents during that time.

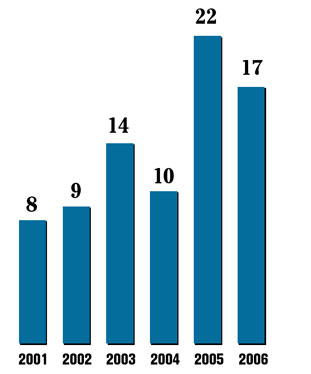

Spinal cord injuries at Hawaii beaches have been rising, to 17 cases in 2006 from eight in 2001, figures show. It peaked in 2005, when 22 people damaged their spines while in the water.

While Waikiki's runner-up placing can be largely attributed to its 6.6 million visitors, Hapuna has all the qualities of a dangerous spot -- inviting medium-size waves breaking above a shallow, hard bottom.

COURTESY BIG ISLAND VISITORS BUREAU

Hapuna Beach had the most spinal-cord injuries in Hawaii with 11.

|

|

Back-breaking beaches

Four of the state's most dangerous beaches for spinal cord injuries are on Oahu.*

| Beach |

Cases |

Estimated yearly visitors |

| 1. Hapuna, Hawaii |

11 |

616,606 |

| 2. Waikiki, Oahu |

8 |

6.6 million |

| 3. Sandy Beach, Oahu |

7 |

383,469 |

| 4. Magic Sands, Hawaii |

6 |

- |

| 5. Waimea, Oahu |

4 |

511,643 |

| 6. Makaha, Oahu |

3 |

385,416 |

Back woes

Spinal cord injuries at Hawaii beaches from 2001 to 2006, according to the Queen's Medical Center Trauma Registry. The data represents about half of all beach-related spinal injuries in the state.

Spinal cord injuries at Hawaii beaches from 2001 to 2006, according to the Queen's Medical Center Trauma Registry. The data represents about half of all beach-related spinal injuries in the state.

|

FULL STORY »

Its shore break doesn't have the year-round, churning surf of Sandy Beach. And its waves are no match to the towering barrels that slam Pipeline's jagged reefs in the winter.

But Hapuna Beach on the Big Island's west coast still sees more spinal cord injuries than any other surfing spot in Hawaii -- and the swell doesn't even have to be very big.

But Hapuna Beach on the Big Island's west coast still sees more spinal cord injuries than any other surfing spot in Hawaii -- and the swell doesn't even have to be very big.

In fact most, if not all, of the 11 swimmers or bodyboarders who hurt their spines at Hapuna between 2001 and 2006 did so when waves were no higher than 4 feet, said West Hawaii District Capt. Chris Stelfox with the Ocean Safety Division.

While the medium-size conditions may look harmless, Stelfox said waves crash over a sheet of water that is sometimes barely knee-deep.

"Those waves break from top to bottom really hard," he said. "People who are inexperienced, they go over the falls head first."

Hapuna, which stretches for 1/3 mile on the Kohala coast, topped a list of isle beaches reporting the most spinal injuries through a six-year period ending in 2006, according to the Queen's Medical Trauma Registry. Waikiki came in second with eight cases, followed by Sandy's, which had seven.

The private hospital's database, the only one that gives beach location of spinal injuries here, accounts for about half of all such cases in Hawaii, said Dan Galanis, an epidemiologist with the Injury Prevention and Control Program at the state Department of Health.

Magic Sands on the Big Island came in fourth place with six cases, ahead of Oahu's Waimea Bay and Makaha, which had four and three respectively. State and city officials noted that one beach missing from the ranking, Kaanapali on Maui, is known for being dangerous, but statistics for that beach were unavailable.

Spinal injuries at Hawaii beaches have been rising, to 17 cases in 2006 from eight in 2001, according to Queen's. It peaked in 2005, when 22 people damaged their spines while in the water, figures show. Figures for last year were not available.

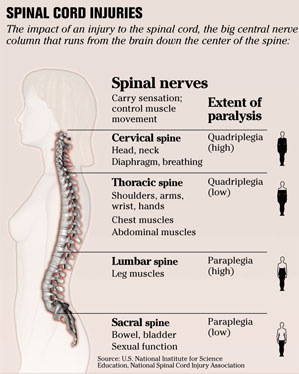

The injuries can range from a pinched nerve, temporary loss of sensation and movement, to paralysis, said Melvin Yee, a neurologist with the Kuakini Health System. Swimmers who damage their spines also can drown or suffer other complications from not getting enough oxygen to the brain before being rescued, said Michon Morita, a Queen's neurosurgeon.

"Sometimes no one notices until the person comes up and they are face-down," he said.

Once mobilized, patients are usually given steroids on their way to the hospital to prevent further damage to the spine, and there are procedures, including surgery, that can relieve stress on nerves and realign bones. But there's little doctors can do to help in severe cases.

"Of the patients who are hospitalized for spinal cord injuries, a fairly large proportion of them don't ever completely recover," Morita said. "One of the big tragedies is that these are very young patients who would potentially have many productive years ahead of them. The cost to them and to their families is tremendous."

Kailua resident Michael Wolper, 46, regular at Sandy Beach for 30 years who has bodysurfed at Hapuna, said his worst wipeout involved a broken arm "on a huge day" at Makapuu Beach. Wolper said he was surprised to learn Hapuna logged more spinal injuries than Sandy's, which is famous for its treacherous and unpredictable shore break.

"I wouldn't think so at all," he said before jumping in the water at Sandy's on a recent morning.

In 1993, Hapuna was named best beach in the country by Stephen Leatherman, a coastal scientist better known as "Dr. Beach." But he cautioned that while Hapuna "is a perfect place to swim, snorkel or scuba dive in the crystal clear waters ... the pounding shore break and powerful rip currents make swimming impossible" in the winter.

JAMM AQUINO / JAQUINO@STARBULLETIN.COM

James Foley is silhouetted against the afternoon sun while practicing a back flip at the Waikiki Beach Wall near Kapiolani Park.

|

|

Most spinal injuries at Hapuna happen in the start of the winter season, when powerful west swells pound its shallow bottom that collect sand during the calm summer months, Stelfox said.

"The sand itself, because it is so fine, it packs really hard, it packs as hard as concrete," he said, adding that Hapuna has permanent signs warning swimmers about its spine-twisting waves. "People say to us, 'Why don't we close the beach down if these injuries are going to happen to the people,' and we can't justify it because the conditions aren't beyond the norm of any other day."

Meanwhile, Jim Howe, Ho-nolulu's chief of lifeguard services, attributed Sandy's third-place ranking to safety measures implemented at the beach since the late 1980s. The first was to relocate one of the two lifeguard towers closer to the beach's main entrance and place warning signs in areas with the most traffic.

"If it was completely flat, with no surf, we wouldn't put the flags up. But that day has not happened," Howe said.

He said officials also partnered with the tourism industry to steer visitors to safer beaches, lectured at schools and launched a junior lifeguard program.

"We recognized that we had a serious problem there," Howe said. "We've raised awareness and I think changed some behavior."

Waikiki, meanwhile, which is better known for a gentle shoreline guarded by wave-breakers, came runner-up to Hapuna. The main culprit was the Kapahulu groin, also known as the "Wall" and a popular diving spot for swimmers and bodyboarders, said Bryan Cheplic, spokesman for the Honolulu Emergency Services Department. He said lifeguards can only advise people not to jump.

City Councilman Charles Djou, who represents Waikiki, said he would consider revisiting a measure -- which failed before the council about seven years ago -- to possibly ban the jumps as long as it captured enough support.

"The past experience has been that people like the fact the Kapahulu groin is open, it's accessible," he said. "We don't want it looking like a fortress."

Staying Safe

» Swim at a guarded beach.

» Read posted warning signs.

» Consult lifeguards about ocean conditions.

» Swim with a companion and make sure children are always supervised by an adult.

» Avoid the ocean if you are intoxicated or under the influence of drugs.

» Observe ocean conditions and currents, which are always changing.

» If you see someone in trouble, call for a lifeguard or dial 911.

» Know your limits. If in doubt, don't go out.

» Enter the water feet first to check depth and avoid diving in head first.

Source: Honolulu Emergency Services Department's Ocean Safety and Lifeguard Services Division

|