GANGS: CRIME CULTURE STILL

ENTICING ISLE YOUTH

FL MORRIS / FMORRIS@STARBULLETIN.COM

"When I got to high school, it was one bigger environment, bigger trouble and I had to stay with somebody for back up."

Bo Acoba, showing his tattoos that once identified him as a gang member.

|

|

‘Money, violence and chicks’

Gangs, off radar, come back

STORY SUMMARY »

First of two parts

For Ryan Beauchan, it all started with pot.

The sixth-grader at Waipahu Intermediate soon began stealing money, jewelry, or anything he wanted, like more weed. Grades didn't matter.

|

BY THE NUMBERS

2.7% Percentage of students who have carried a handgun

4.75% Percentage of students who have been arrested

5.68% Percentage of students who have sold illegal drugs

11.3% Percentage of students involved in gangs

47% Percentage of students with family conflict

Source: 2002 Hawaii Student Alcohol, Tobacco, and Drug Use Survey

|

His habits went unnoticed by his father, an unemployed drug addict with a heavy fist. His mother worked all day, sometimes all night.

"Home wasn't home," Beauchan responds when asked why he joined a gang. "Home was my friends."

In high school, one such friend was Bo Acoba. He was failing school, his parents were going through a divorce.

The two had a bond, and a good time.

"It was just straight up making money, violence and chicks," says Acoba.

It has been a decade since teenage gangs started to decline in Hawaii because of programs and partnerships created to address what was then considered an epidemic. But the problem did not vanish.

In fact, social workers, school principals and observers worry that gangs could be returning, citing a spike in school fights, the homeless crisis and an influx in immigrant students. And the problem, they say, is getting worse because the state is not paying close attention.

State law enforcement, education and human service officials dispute that claim, arguing they are keeping gangs under control.

FL MORRIS / FMORRIS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Bo Acoba, 17, shown in his family home in Waipahu, he had dropped out of Waipahu High School before getting counseling with Adult Friends for Youth, where he recently completed an eight-month anti-gang program.

|

|

FULL STORY »

BO ACOBA, a lone troublemaker in middle school, started hanging out with a group of students for protection during his freshman year at Waipahu High School.

With his "boys" at his side, the then 15-year-old used and sold drugs, got drunk, carried weapons, cut classes and made more use of his fists than his head.

"When I got to high school, it was one bigger environment, bigger trouble, and I had to stay with somebody for backup," explains Acoba, who has the word "respect" tattooed across one forearm, "and that's why I joined the Barcadas."

So it was out of loyalty, he says, that he stabbed two students from a rival Kalihi gang two years ago when his friends were outnumbered in a territorial brawl. The injured students did not press charges, which Acoba says proves he acted in self-defense.

But on that Halloween night - as Acoba tossed his knife into a stream and burned his bloodstained clothes - he discovered how quick his life could have slipped away if he were at the opposite end of the blade.

"You realize after that, what if somebody shoots you, or robs you, what if you get lickin's like that? No matter how high you go, you always come down," says Acoba, who dropped out of high school, but later started going to counseling with Adult Friends for Youth, a nonprofit anti-gang group.

Acoba escaped gang life but social workers and observers worry that more at-risk isle students, like Acoba, are turning to gangs. And they complain that the state has ignored gangs by cutting programs credited with bringing the problem under control about a decade ago.

Citing an increase in public school fights, Adult Friends for Youth is concerned about a resurgence in teenage gangs that slowed around the mid-'90s with a truce between two large Filipino gangs from Kalihi, the Pinoy Boys and the Cross Sun. The organization, which formed in 1985 to control gangs, has contracts on Oahu with four public high schools, two middle schools and one intermediate school to work with dozens of teenage gangs involving more than 300 students.

But whether that number represents a majority or a small fraction of gangs at Hawaii schools is unclear.

It has been five years since the state last examined the issue in a survey that found 1 in 10 isle students had been part of a gang at some point. The findings were analyzed in a 2005 University of Hawaii study that faulted the monitoring of gangs in the islands and cautioned about a mind-set of denial.

State law enforcement, education and human service officials say they offer enough services to stop children from entering gangs, disband current groups and avoid chaos. Although public school fights are up, officials argue they are not as violent or as frequent as in the late 1980s and early '90s.

Deborah Spencer-Chun, who heads Adult Friends for Youth, said employees build relationships with gang leaders to learn about brewing fights. But, she said, they are increasingly unable to answer campus disturbances on time.

GEORGE F. LEE / GLEE@STARBULLETIN.COM

Deborah Spencer-Chun, who heads Adult Friends for Youth, says, "Sometimes it takes a real crisis before anybody responds to it. People don't want to believe there are gangs in those neighborhoods just like people don't want to say there are gangs in Hawaii."

|

|

"Sometimes it takes a real crisis before anybody responds to it," she said. "People don't want to believe there are gangs in those neighborhoods just like people don't want to say there are gangs in Hawaii. This is paradise, this is where most of our economy comes from tourism."

While not in full agreement about the gang threat, school principals, social workers and observers acknowledge the potential is there.

"It's certainly a time to not assume that everything is fine," said UH criminologist Meda Chesney-Lind, who has done extensive research on gangs in the state.

"I view it as public health issue," she adds, "where if you don't pay attention to a kind of problem, it eventually comes back to haunt you. And I think that's where we are at with the gang problem. We have kind of taken our eye off the ball. Even with those specific incidents, we are not seeing the mobilization that you should see."

Those incidents included:

In March, more than a dozen police officers arrested 11 students in a fight at Nanakuli High and Intermediate School, and Farrington High School was placed on lockdown after two gangs clashed on campus.

Six months earlier, on Sept. 27, 2006, an argument between two students over a girl sparked a gang conflict at Farrington. An 11th-grade boy lost an eye to a shot from a pellet gun fired by a former student who had been suspended in a previous gang incident, according to a University of Hawaii review of the case.

During that scuffle, a student from an adult program at McKinley High suffered wounds to his torso, scratches and bruises on his back, head and eye. Another student received a head injury. Eight people were arrested, and the school band, the girl's softball team and cheerleaders had to end practice and go home.

|

GANG FIGHTS

Recent school fights at Oahu public schools:

2007

» Oct. 18: Leilehua High School was placed under its "highest state of alert" and police officers were brought to campus after a fight involving a dozen students.

» March 8: More than a dozen police officers responded to a fight at Nanakuli High School. Eleven students were arrested.

» March 9: Two gang-related fights forced Farrington High School into lockdown.

2006

» March: Video posts of two fights and associated taunting between students of Campbell High and Farrington High blew up into a major confrontation leading to several arrests.

2005

» February: Eight Nanakuli High School students are arrested on suspicion of disordely conduct.

|

"All of the students were kind of taken aback by that and it became a great, great concern for them," said Farrington Principal Catherine Payne, who has since hired three additional security guards to scan school entrances. "It is an issue in the community, and schools really reflect the community and we need to deal with those things that are out there."

Payne has doubled spending on anti-gang programs to $20,000 over the previous school year and reinstated a policy discontinued five years ago that requires gang leaders to meet weekly. There has been one fight at the campus so far this year, she said.

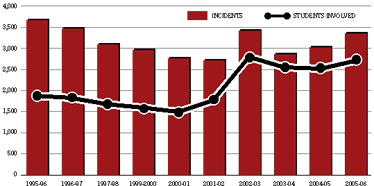

ACROSS THE STATE, school violence has risen in the past three years to levels experienced in the mid-1990s even as fewer students enroll in the public system.

Ten years ago, when enrollment peaked with more than 189,000 students, there were 3,086 reported incidents of violence involving 1,720 students. In the 2005-06 year, despite a drop of nearly 8,000 schoolchildren, violence rose to 3,350 cases in which 2,762 students took part, according to the state Department of Education.

That's an 8.5 percent increase in cases and a 60.5 percent hike in the number of students participating in assault, robbery, sexual offense, terroristic threatening, harassment and possession of weapons and firearms.

In 2005, Chesney-Lind joined seven researchers to write the last study for the now-defunct Hawaii Youth Gang Response System, or YGRS, which urged officials to expand and review prevention efforts and gather more reliable data, concluding that "Hawaii could in fact be entering a period of denial of gang problems, complete with an absence of media attention perhaps due to the island's tourist economy."

The 108-page report, "Gangs in Hawaii: Past and Present Findings," had trouble assessing gang trends since 2000, when a system that tracked information like name, age, ethnicity and even tattoo patterns throughout the 1990s was replaced by other software that gathered incomparable data.

"Therefore, police data on gangs can no longer be used by researchers for analysis on the extent of the gang problem," it said.

Before it was phased out by the Honolulu Police Department, the Gang Reporting Evaluation and Tracking System had the number of gangs rising to 192 from 45 between 1991 and 1996 - a 326 percentage change increase - and membership jumping from 1,021 to 1,900.

But in 2002, the new Hawaii Gang Members Tracking System reported an unknown number of gangs and 736 members, according to the study.

Despite the report's recommendations, the state's 16-year-old gang response system was discontinued in the summer of 2006 because of funding priorities and disinterest from people involved, said Jessica Kim-Campuspos, a children and youth specialist with the state Office of Youth Services.

The office, which did not update the 2003 YGRS gang report to give more money for programs working directly with children, remains interested in carrying out a new study but has not yet scheduled one, she said.

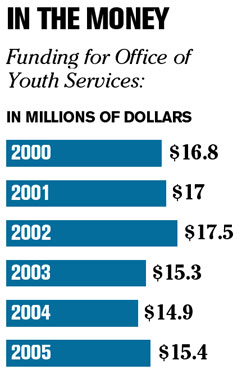

The agency got $15.4 million in combined state and federal funding in the 2005 fiscal year for intervention and education services and to manage the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility. That's a $500,000 boost from the previous year but $2 million shy of what it got in 2002.

Lisa Nagamine, who worked at Waipahu High as a special motivations teacher for nine years beginning in 1989, said she misses the cooperation between police, social workers and schools under the YGRS - a partnership she says helped educators flag and support the most at-risk students on campus.

Lisa Nagamine, who worked at Waipahu High as a special motivations teacher for nine years beginning in 1989, said she misses the cooperation between police, social workers and schools under the YGRS - a partnership she says helped educators flag and support the most at-risk students on campus.

"Working together with HPD really helped us out. It was really neat," Nagamine said, saying students turned to drugs and fell into gangs to deal with bad grades and problems at home. "They were always told they couldn't do it. They were always told they were stupid, or 'You are nothing, you are a loser.' So it was safer for them not to try."

Information previously collected by HPD allowed schools to identify gang members through tags or clothing, said Kapolei High School Principal Al Nagasako. But since the program ended, Nagasako has had to rely on five security guards out of his school budget for security.

"It has put a big strain on schools because you got to spend a lot of time and effort on security issues," he said. "We are instructional leaders, not cops, but we got to be on our watch all the time."

HPD replaced its gang detail a few years ago with a statewide graffiti task force that meets monthly with volunteer groups like Weed and Seed, said spokeswoman Michelle Yu.

While graffiti arrests appear to be going up, with 185 people caught for the offense in the first seven months of the year compared with 294 for all of 2006, the number of gang-related tags remain stable, Yu said.

Officers also have two other gang prevention programs: Positive Alternative Gang Education and Gang Resistance and Education Training. Police declined to say how much money the programs have gotten in recent years.

"Since the early '90s, it (the gang problem) has declined, and we do have isolated incidents, but it's always a problem and so that's why our position is we are going to continue to teach kids to stay out of the gangs," said Sgt. Darren Evangelista, director of the federally funded GREAT program.

The 13-week course, considered the top gang prevention tool in Hawaii since 1999, has explained the danger of gangs to thousands of seventh-graders at 23 middle schools and one elementary school on Oahu, he said.

"All we can do is try to control it," Evangelista said. "It is never going to be completely gone."

This summer, Bo Acoba, now 17, graduated with 20 classmates from an eight-month anti-gang program. He plans to attend college in Las Vegas in the spring to start over, he said, adding, "I know I can change from there."

» Tomorrow: Even for the most at-risk students, there's hope.

More fights, more students involved

School violence has been somewhat stable in the past decade despite increasing enrollment in the public system. Meanwhile, the fights are increasing involving larger groups of students.

STUDENTS IN SCHOOL

School enrollment in Hawaii public schools since 1995:

| School Year |

Enrollment |

| 1995-96 |

186,805 |

| 1996-97 |

188,465 |

| 1997-98 |

189,281 |

| 1999-2000 |

185,036 |

| 2000-01 |

183,520 |

| 2001-02 |

183,629 |

| 2002-03 |

182,798 |

| 2003-04 |

182,434 |

| 2004-05 |

181,897 |

| 2005-06 |

181,406 |

GETTING HELP

Schools that have contracts in the 2007-08 school year with Adult Friends for Youth to control gangs, and their enrollment.

| Kapolei High |

2,285 |

| Campbell High |

2,491 |

| Farrington High |

2,530 |

| Waipahu High |

2,564 |

| Central Middle |

457 |

| Kalakaua Middle |

1,039 |

| Waianae Inter. |

1,029 |