COURTESY BILL SHARP Liu Ping addresses the People to People International group. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

From Red Guard to global entrepreneur

A product of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Ping now leads the business world

Look East / Bill Sharp

BEIJING » Employing more than 30 workers, housed in a spacious spic-and-span office in trendy, upscale Northeastern Beijing, it is hard to believe that Liu Ping, 52, founder and general manager of Star Professional Programs, was once a Red Guard who passionately idolized Mao Zedong.

Born in 1955 in Northeast China's Liaoning Province, she is the eldest of four children. Pictures of the house where she was born reveal her parents were people of modest means. Answering Mao's call to develop China, her father and mother, both loyal members of the Chinese Communist Party since before the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, moved from the Northeast to backward Guizhou Province, in the Southwest, to work in low-paid mining jobs.

Look East

Bill Sharp |

Ping has a unique view of Chinese political life, having lived through the Great Leap Forward (1958 to 1961) when Mao encouraged peasants to smelt steel in their backyards in order to rapidly surpass Britain in steel production. The GLF was not only a colossal failure at producing steel, it also led to the mass starvation of an estimated 30 million Chinese. Ping recalled that Communist Party cadre blamed the failure of the Leap on weather conditions.

Ping was a junior high school student in Guizhou when the most profound political event of post-1949 China swept through the country. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a nationwide attempt by Mao to purge the party of capitalist roaders -- those more interested in building China's economy than with creating the new socialist man or philosophizing about Marxist-Stalinist-Maoist thought.

To ensure that revolutionary zeal was passed on to China's youth, Mao created the Red Guards (hongweibing), who were to study, learn and promote revolution to help Mao ensure that party members taking the capitalist road were permanently extirpated.

Because of her singing and dancing talent, Ping was recruited by a Red Guard propaganda team when she was just 12 years old. She acted in skits, sang songs and performed dances, all designed to inculcate audiences in revolutionary Maoist thought. Asked why she joined the Red Guards, she responded, "There was not really any choice. They came to get me one day, and my parents didn't say a thing. They couldn't, given the nature of the times. Everyone had unswerving faith in Mao. It was a national craze." Listening to her relate her Red Guard experiences, it is apparent that from childhood she has had a deep love for China that the Red Guards allowed her to express.

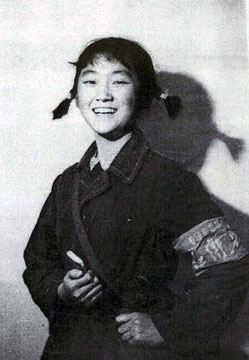

COURTESY BILL SHARP Above, Liu Ping posed for a photo clutching Mao's Little Red Book during her Red Guard days. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

Mao himself ultimately acknowledged that the Cultural Revolution had gotten out of control and called in the People's Liberation Army to restore order. Ping began to lose interest after seeing her father paraded through the streets as a capitalist roader.

Her Red Guard days over, Ping went to work in a factory making explosives and soon became the only female underground mining electrician. She won the praise of fellow workers; they recommended her for admission to Guizhou University where she wanted to study electrical engineering. However, the demands of the state prevailed, and she was directed to study English, she said.

After graduation in 1976, Ping was a junior high school English teacher in Guizhou Province for a few years. .

In 1978-1979, with Deng Xiaoping restored to power, China opened itself to the world. Tourists from abroad began to flow into China. Using her English skills, Ping became a government official, working for a large state tourism corporation that welcomed visitors from abroad. Working for the government gave her a good foundation in the tourism industry. But China's "everyone eats from the same pot" concept encouraged lackadaisical work habits, which saw many employees reading newspapers, drinking tea, smoking cigarettes and generally avoiding work. In contrast, Ping developed a reputation as an ambitious employee with an outstanding record of nailing down important accounts.

In 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization. To Ping, the WTO represented an opportunity to run a travel agency based on internationally accepted standards of good management. She resigned from her government job and set out to start her own company. If successful, she said, her company would give her more money, allow her to develop management skills, provide for family members, save for retirement and pass something on to her son.

Like many early Chinese entrepreneurs, Ping borrowed 1.5 million yuan ($20,000) from her friends and rented a small office. Securing a license was a tricky process. She rented a license from a travel company that had gone out of business. Finally, after more than two years, the license was all hers.

Her company, Star Professional Programs, specializes in highly tailored tours for single travelers or groups of international travelers with particular interests, such as lawyers, doctors, educators or business executives. She also organizes conferences. Central to her management style is long-term planning, constant staff training,and a deep concern for branding. If that sounds like something straight out of business school, it is -- Ping just completed an MBA program.

Her success is obvious and she can often be found working at her desk long after staff members have left. When she finally returns home to Beijing's posh Shunyi Villas, where she owns three units, she is chauffeured in her new Mercedes S-Class. Interestingly, she calls herself highly successful, but also "middle class." She readily admits, as do other Chinese, that one of China's biggest problems is unequal distribution of income.

Given her background and her success under Chinese economic policies, one might assume she is a Communist Party member. She is not. She said she has been repeatedly coaxed by party officials, but she has declined, wishing to avoid internal party politics and the demands on time that membership would require.

However, she has not removed herself from politics altogether. Ping is an active member of the Jiusan Society, one of eight recognized political parties, which maintains a membership of 88,000. Like the other democratic parties, Jiusan Society members discuss a wide variety of problems confronting contemporary China. Once they have arrived at a consensus, they bring their concerns to the attention of the local committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (referred to by some as the upper house of the Chinese legislature), which considers the merits of the issue and either tries to solve the problem or dismisses it.

Ping said she feels that liberal Western democracy will not come to China during her lifetime and that given the geographic size, huge population, and uneven economic and human development of China, democracy is not appropriate. Many Chinese see Western democracy as being dysfunctional and place greater value on unity and stability. She does, however, stress that decision making in China is not top-down, as was typical in Mao's day. Consensual decision making involves far greater numbers of citizens, she said.

Ping is performing a far greater service to China than merely joining the party. Internationally, she is chairwoman of the Beijing Chapter of People to People International, which was started by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to enhance intercultural communication. Through the organization and her company, she helps explain China to hundreds of influential international tourists each year.

In her words, "I want others to understand China." Thus the girl who joined the Red Guard out of a love for China is today the successful entrepreneur who ever still loves her country.

Bill Sharp teaches domestic and international politics of East Asia at Hawaii Pacific University. He writes a monthly commentary for the Star-Bulletin. wsharp@campus.hpu.edu