JAMM AQUINO / JAQUINO@STARBULLETIN.COMA photograph of Victoria Kaiulani is among the portraits showing at Mission Houses Museum in the exhibit "Larger than Life: Portraits and Portrait Making." CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

Historical identity

Portraits at a missionary museum illuminate isle life

OUTSIDERS to Hawaii, no matter how schooled in its history, share that startling first experience of encountering Hawaiian royalty photographed in starched Victorian dress: The intense gaze and bearing of pedigreed Polynesian nobility, coupled with those incongruous frilly dresses, tall hats and stiff collars, lets the viewer absorb the conflict and contradiction of the colonial era better than a thousand words.

Combine that with the universal, complex ability to instantaneously decipher the human face, and you have the foundations for the debut exhibition by new executive director David de la Torre at the Mission Houses Museum, "Larger Than Life: Portraits and Portrait Making."

'LARGER THAN LIFE'

Portraits and Portrait Making

» On view: Through Sept. 22

» Place: Mission Houses Museum, 553 S. King St.

» Hours: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays

» Admission: $6

» Call: 531-0481

|

De la Torre, formerly a program director at the Hawaii State Art Museum and associate director of the Honolulu Academy of Arts, brings 30 years of curatorial experience to an often overlooked history museum that begs to be seen with new eyes.

"It was an opportunity that I was drawn towards the more I started to talk with the board about the needs that the institution has to make its collections more accessible," de la Torre said of his change of direction. "I'm really into the object and there's nearly 16,000 objects here. The first portrait show is giving me an idea of what can be done."

Future exhibits in the series might showcase the museum's collection of kapa, or tortoise shell implements and keepsake locks of hair. Printing and bookmaking offer opportunities to look at the missionary contribution to literacy, while toys, food and religious altars could introduce ways to "draw in multicultural traditions" and "create a forum for people to talk about their own stories, their own backgrounds."

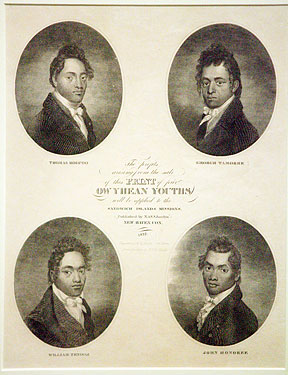

COURTESY MISSION HOUSES MUSEUM An engraving of "Four Hawaiian Youths" are on exhibit at the Mission Houses Museum. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

PORTRAITS are most interesting, of course, when their subjects are familiar. So there is an inherent fascination for local audiences in a rarely seen painting of, say, the legendary beauty Victoria Kaiulani, daughter of a Hawaiian noble and a Scottish financier and heir to the Hawaiian throne. The subject of a 1930 oil painting in the Mission Houses Museum exhibit "Larger Than Life: Portraits and Portrait Making" has the slightly tarty look of a fashion pin-up; right beside it, a photograph from a slightly younger age gives a totally different impression. One reads in the princess's introspective expression something like the graceful resolution of ambivalence, which must have appeared to Europeans of the time as an unnameable beauty.

Indeed, much can be understood about the colonial era just from the exhibit's portraits of native Hawaiians as painted and as photographed. Colonial artists plainly struggled with non-European physiognomy, sticking onto Western features exaggerated, wide-set eyes and full lips, turning the engraving "Four Hawaiian Youths" into cookie-cutter quadruplets.

Photographs, by contrast, can burn with an intensity that spans the decades, from a tiny photograph of Kamehameha III on an antique button (what one would give to own that!) to a gorgeous, haunting, hand-tinted daguerreotype of Lucy Moehonua, wife of an adviser to the Kamehameha court, that is perhaps the highlight of the exhibit.

Portraits of the missionary families reveal their own, unexpected ambivalence. Known primarily through their texts and the occasional astringent photograph, the missionaries as painted show considerably more mixed resolve.

An 1850 oil painting of Laura Fish Judd, wife of Dr. Gerrit Parmele Judd, has a softness and vulnerability about the face that is nearly absent from missionary photographs of the era, which required sitting frozen in the discomforting awareness of being documented for eternity.

All of these elements of portraiture -- the artist's projections, the subject's self-awareness, photographic technology, conventions of gesture and bearing, not to mention filtering by the modern viewer -- add up to the complex sum of historical identity, which is not as factual as it reads on the history-book page.

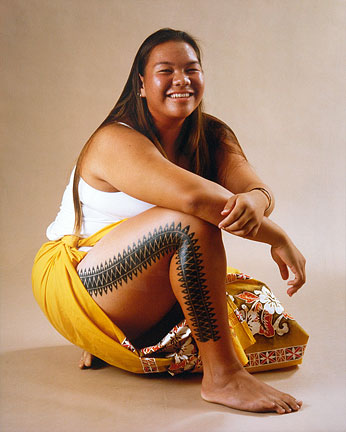

COURTESY MISSION HOUSES MUSEUM Contemporary portraits, like the one at left by Shuzo Uemoto of Chelsea Nahalea, sporting the tattoo work of Keone Nunes, illustrate how identity is tied today to individuality. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

To carry that point home, curator David de la Torre has included in a separate room contemporary portraits by local artists Joseph Singer, Shuzo Uemoto, Franco Salmoiraghi, Mark Kadota and others. We see that everything has changed in the space of a century, and not only because of advances in photography. Today, identity is clearly tied to one's "image," and it is individuality as expressed in clothing, gesture and "attitude" -- rather than one's status of belonging to a certain class or tribe -- that matters.

The labels in the Mission Houses exhibit encourage this kind of awareness, asking viewers to consider how "likeness" plays into our individuality, or what our objects might say about our culture and society.

COURTESY MISSION HOUSES MUSEUM A hand-tinted daguerreotype of Lucy Muolo Moehonua, wife of an adviser to the Kamehameha court. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

Such a studied, postmodern approach to history is clearly crucial to the future relevance of the Mission Houses Museum, operated by a 150-year-old charitable society of such venerable island names as Atherton, Cook and Baldwin.

Amid the current preference of many tourists and local aesthetes for things native Hawaiian, de la Torre aims to nurture a more inclusive view of the past by presenting, via objective evidence, "the cycles of when segments of the society are marginalized or denigrated or illuminated."

"We have the written history, which is a reason to have (the Mission Houses) library," he says. "But then we have a popular history, which is in our mind's eye, and that is very difficult to change" -- such as the popular understanding of the missionaries as Eurocentric oppressors who tried to obliterate a unique way of life.

COURTESY MISSION HOUSES MUSEUM Centuries ago the portrait stressed the subject's status of belonging to a certain class or tribe. Above is an oil of Laura Fish Judd from 1850. At top is a hand-tinted daguerreotype of Lucy Muolo Moehonua, wife of an adviser to the Kamehameha court. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

The goal is not to proselytize for the missionaries, de la Torre says, but "to make the museum essentially a 19th-century museum about the American Protestant experience in Hawaii, and connect that to a broader history of Hawaii."

Engulfed on all sides by downtown Honolulu's car dealerships and designer showrooms, sandwiched between the Kamehameha Schools headquarters and Kawaiaha'o Church, the Mission Houses Museum's rummaging in its 19th-century attic points to a creative, unexpected solution to joining the complex collage of the present.