ASSOCIATED PRESS The Dalai Lama bowed as he was surrounded by Hawaiian elders Wednesday during a visit to Maui. The 71-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner and spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists made his third visit to the islands last week. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

The Right Dalai Lama

A journalist's frenzied odyssey to make photographic history ends in a bar in Calcutta

By Jim Becker

|

MORE THAN 20,000 people sought out the words and wisdom of the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet, when he visited Maui last week. He joined hands with Hawaiian elders, patted the cheeks of island keiki and walked a celebrity rope line shaking hands with admirers. The holy man's visage -- bald pate, wire glasses, scarlet robes and ever-present smile -- is recognized around the globe. But it wasn't always so. There was a time -- before he fled Tibet in 1959 ahead of the Chinese invasion -- when few Westerners had ever seen him. Even photographs were rare. Jim Becker, a Honolulu writer and former Star-Bulletin columnist, was working for the Associated Press when the mysterious "god-king" arrived in India to begin a life in exile, and was among the many foreign correspondents racing to get that first picture of the Dalai Lama and transmit it to the world. The story of the photograph that launched the holy man's celebrity is the opening chapter in Becker's 2006 memoir, "Saints, Sinners and Shortstops" (Bess Press).

Editor's note: The following story is the first chapter in Jim Becker's "Saints, Sinners and Shortstops," his 2006 memoir recounting his life as a journalist, including stints as a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press and as a columnist for the Star-Bulletin.

Chapter One: Urgent Becker -- The Right Dalai Lama

At least two movies have been made about his life and he has appeared on almost every TV talk show on three continents over the years, but there was a time when the 14th Dalai Lama, the Tibetan "god-king," was the most mysterious human being on earth. Photographs of the Dalai Lama were as rare as interviews with Greta Garbo or World Series victories for the Chicago Cubs.

It was once claimed that only seven Westerners had ever set eyes on the Dalai Lama in his secluded Himalayan Kingdom. One of them, Heinrich Harrer, a German who spent seven years as an advisor to the Dalai Lama and wrote a book about it, has had his life made into movie, too.

So in April of 1959, when the Dalai Lama decided to flee, on foot, to India ahead of the Chinese takeover of his country, it was the major international news story of the day. The usual suspects among the foreign corresponding corps, of which I was one, were dispatched to India to report on and, most importantly, to photograph his flight to freedom.

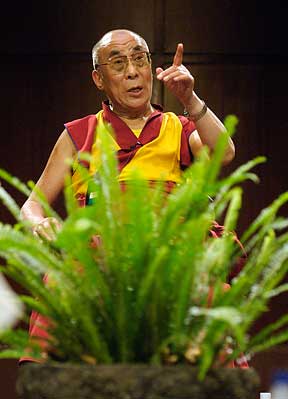

ASSOCIATED PRESS The Dalai Lama spoke about Tibetan Buddhist teachings and human rights during a talk Wednesday at War Memorial Stadium in Wailuku. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

The Indian authorities, including Prime Minister Nehru who had grudgingly granted asylum to the Dalai Lama -- the Chinese were touchy on the subject -- arranged for the exile and his entourage to enter India at a town called Tezpur, which had an airstrip and the communications with the outside world needed to carry the report to the headquarters of all news organizations.

Photographs, however, were another matter. Given the primitive communications of the day (no cell or video phones; even satellites were not in general use), the only method of dispatching photographs was via a single "Radiophoto" circuit from Calcutta, several hundred miles southeast of Tezpur, to London.

The Radiophoto circuit could send but one picture at a time, and each took nearly 20 minutes to transmit.

The circuit was the target of the two major news agencies in the field. The one who managed to convey a photograph from Tezpur to the Radiophoto office in Calcutta and file it first would score a considerable journalistic scoop, a word then still in vogue.

I did everything I could think of to ensure that AP would file that first picture. I chartered an airplane to fly the film from Tezpur to Calcutta. (So did UPI.) I arranged for a fast car with a manic driver to speed the precious cargo from the airport to the Radiophoto office in town on a dusty, two-lane road crammed constantly with sacred cows, jaywalking villagers unaware of the threat posed by a speeding motorcar, pedicabs, pushcarts and countless pye-dogs who moved reluctantly from their resting places in the middle of the road. I engaged a crew of Indian boys with AP signs to form a human chain that would direct us from the airplane to the waiting car. And I bought the only photographic shop with a darkroom in the vicinity of the Radiophoto office. (One of the best deals AP ever made; after the event I sold it at a slight profit.)

Then there was nothing to do but wait. It was a dangerous time in South Asia. India and Pakistan were growing increasingly antagonistic, a feeling that would build into a major shooting war in a few years. The Chinese were exceedingly anxious about intrusions into their air space, which they declared now included Tibet. This precluded any attempt to fly into it to check on the Dalai Lama's progress.

Nehru was nervous, too. He hated the spotlight beaming on his impending guest at a time when he was trying to placate his Chinese neighbors. Border skirmishes and discrepancies between Indian and Chinese maps had resulted in a sometimes acrimonious exchange with China in the 1950s called Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai (Hindi for "India and China are brother"). Nehru got a shooting war with China in 1962 for his pains.

In the midst of these powder kegs, the gaggle of foreign correspondents gathered at the Great Eastern Hotel in Calcutta, eyeing each other warily, and waiting for the signal to fly to Tezpur and meet the mysterious refugee.

During this vigil, a correspondent for the Daily Express of London, then a newspaper with pretensions of importance, decided to give us a lesson in British tabloid journalism. The correspondent excused himself from a gathering in the hotel bar -- just as his turn to buy a round approached -- and was gone for half an hour or so. Not long after his return, many of us received angry cables from our home offices demanding that we match an exclusive Daily Express story describing in copious detail the Dalai Lama's entourage as it made its way through the foothills of Tibet to impending freedom in India.

The Express correspondent had, of course, repaired to his hotel room and concocted the story out of whole cloth. It began with the fetching lead, "I flew over the Dalai Lama today," went on to name the plane's pilot (a fictitious tea planter), and described in flamboyant detail the spinning prayer wheels and fluttering banners of the procession.

ASSOCIATED PRESS The Dalai Lama got friendly with members of the crowd who came to hear him speak at War Memorial Stadium in Wailuku, Maui. CLICK FOR LARGE |

|

Juicy stuff, to be sure, and invented within the walls of his own hotel room. I'd been in the business for 15 years by then and I was outraged at this exercise in journalistic fiction. Several of my colleagues, on the other hand, like the characters in Evelyn Waugh's great newspaper novel Scoop, were angry only that they hadn't thought of the ruse first.

Soon after, word came that the Dalai Lama and his party were indeed approaching the Indian border, and we all flew to Tezpur to cover the real story, and to take those precious photographs and rush them back to the Radiophoto office and file them -- FIRST!

The refugee procession made it into town. There were no fluttering banners or spinning prayer wheels, just dusty shaven-headed monks in saffron-colored robes, including the Dalai Lama himself, a small and shy man who nevertheless appeared pleased to have reached safety.

The Dalai Lama was led to a platform and a microphone which the Indian government had provided for a news conference. Standing alongside his interpreter, a husky Indian with a beard and a lovely head of wavy hair, he submitted to questions from the press corps. He had no English at this time, and was very cagey in his own language, perhaps because in his wildest nightmares he'd never dreamt of venturing so far from his sheltered palace or subjugating himself to the scrutiny of so many strange-looking individuals.

After the conference we wrote and dispatched our stories, and then the race was on to get the pictures to the office in Calcutta, and thence to London and the waiting world.

The plane carrying AP's precious cargo of film, and the less important occupants such as the photographer and me, sped down the runway and took off almost simultaneously with the UPI plane.

Whereupon my best-laid plans began immediately to unravel. The direct route, and the fastest, from Tezpur to Calcutta was right over India's neighbor, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The previous day, the Pakistanis had shot down an Indian Air Force plane that they claimed (probably correctly) was taking pictures of Pakistani military installations, and they announced they would shoot down any other planes intruding in Pakistani airspace.

This warning was not lost upon the pilot of the AP plane. He refused to risk the direct flight, choosing instead to fly around East Pakistan, adding at least half an hour to our flight time. The UPI pilot apparently had no such fears, and fortunately for him, if not for me, was not shot down.

Hence when the photographer and I arrived at the Calcutta airport we were informed that the UPI plane had landed well before us. We did our best to make up the time. We dashed down the chain of AP signs to the waiting car, whose driver blew his horn non-stop all the way to town, scattering cows, roosters and villagers with no distinctions. We rushed into our darkroom, developed three photos -- the limit was three -- and I hustled next door to the Radiophoto office with three wet prints over my arm. Too late. Three UPI Radiophotos were on file ahead of me, and the first one was just about to be transmitted. I had lost in a photo finish, thanks to a chicken pilot.

This defeat did not escape the attention of the AP photo editors in London. Within minutes I received the first of an increasingly furious series of cables, all marked URGENT, at about two bucks a word. It read:

URGENT BECKER UPI DALAI LAMA PHOTO ROLLING NOW HOW OURS PLEASE. AP PHOTOS LONDON

In journalistic cable-ese, "HOW OURS" is not a polite request for feeble excuses about craven pilots. It is a scream of anguish, a veiled threat that you can be replaced, a demand for action.

I tried bribery, cajolery, even threats of suicide in an attempt to get one of my photos moved up in the queue, to no avail.

Soon came a second cable: URGENT BECKER SECOND UPI DALAI LAMA PHOTO ROLLING NOW OUR SUBSCRIBERS UPSET ANXIOUS. AP PHOTOS LONDON

The third one was even nastier.

I began contemplating another line of work, something less stressful, after I received the following:

URGENT BECKER OUR FIRST DALAI LAMA PHOTO ROLLING NOW FIFTY SEVEN MINUTES AFTER OPPOSITION. AP PHOTOS LONDON

Bad news, indeed. But within minutes the sky cleared and the birds began to sing and all was right with the AP world. I was handed a fourth cable:

URGENT BECKER UPI DALAI LAMA FULL HAIRED. OUR DALAI LAMA SHORN CLARIFY URGENTLY. AP PHOTOS LONDON

And I knew right away that God had saddled me with a cowardly pilot but he had more than leveled the playing field by matching me with a UPI correspondent named Earnest Hobrecht, who was almost certainly the only member of the entire foreign press corps who had no idea what the real Dalai Lama must look like.

People who worked with him told me that Ernie was one of those journalistic accidents, a classic example of the Peter Principle in action. He was, I believe, a salesman who was promoted to newsman when a vacancy suddenly appeared and he was available. He probably could not have located Tibet on a map and he was obviously uninformed about the tonsorial habits of Tibetan monks.

Ernie had sent three Radiophotos of the wrong man. He had sent photos of the wavy-haired and bearded Indian interpreter, who was, after all, the man standing behind the microphone. And to make certain that a good clear picture emerged at the other end of the Radiophoto circuit, Ernie had carefully cropped out of each picture the insignificant shorn man in the monk's robe who was standing next to the Indian interpreter -- the Dalai Lama.

Two things then happened simultaneously. One man handed me a copy of the The Statesman, the excellent newspaper published just down the street, and he passed me another cable from London. I looked at The Statesman first. There, on the front page was a huge, six-column blank space. It was where a photo of the Dalai Lama was to have appeared. Then I read the cable:

URGENT BECKER UPI SENT THREE RADIOPHOTOS OF THE WRONG MAN AND WERE FORCED TO KILL THEIR PHOTOS ALL OVER THE WORLD REGARDS AP PHOTOS LONDON

Regards indeed. The first kind words I had heard all day.

All became clear. The Statesman had planned to run the photo six columns wide on its front page, and received the KILL order just in time to chisel the photo out of the plate used to print the front page, leaving a huge blank space.

I then wrote the cable that has passed into journalistic legend:

URGENT AP PHOTOS LONDON THE BEST DALAI LAMA IS THE RIGHT DALAI LAMA. REGARDS BECKER

I went back to the hotel, where the news of the killed photos had preceded me. The assembled press corps insisted that I mount the bar and relate, in detail, the tale of the right Dalai Lama.

Ernie was not there to enjoy it. He had retired to his room and did not emerge for two days. The next I heard of him, he was selling real estate in Oklahoma, I believe.

When I finished the story, grown men collapsed around me in tears of joy and spasms of laughter.

When composure was restored, several members of the audience insisted that I tell it again, and I did, and I have ever since, at the gatherings of foreign correspondents, in Tokyo or Washington, New York or London.