IN THE MILITARY

The intrepid interpreters

A new book tells how nisei translators helped win World War II

ARMY HISTORIAN John C. McNaughton has worked for nearly two decades on the first official history of the 6,000 Japanese-American Army linguists credited by many with altering the outcome of World War II.

Besides providing a synopsis of the history of the Japanese in Hawaii and the mainland, McNaughton's book -- "Nisei Linguists" -- traces the beginnings of the Military Intelligence Service that began months before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor with the Fourth Army Intelligence School at the Presidio in San Francisco. The book comes out March 20.

During the war, the Military Intelligence Language School operated in Minnesota at Fort Savage and Fort Snelling. By the spring of 1946, the school graduated 6,000 linguists. The book, in great detail, retraces the war in the Pacific and the contributions of nisei linguists in places like China-Burma, the Philippines, Okinawa, the Aleutians, Guadalcanal, Guam and postwar Japan.

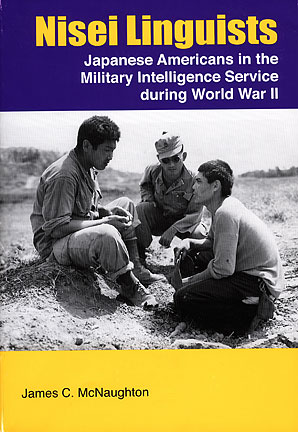

COVER PHOTO FROM NATIONAL ARCHIVES

John C. McNaughton's 514-page "Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Service During World War II," will be officially released on March 20 in the U.S. Senate Russell Office Building with Hawaii Sen. Daniel Akaka officiating over the ceremony. Co-sponsors of the event are the U.S. Army and the Japanese American Veterans Association. On the cover, 7th Infantry Division Sgts. Hiroshi "Bud" Mukaye, left, and Ralph Minoru Saito, center, question a Japanese sailor at Okinawa on June 17, 1945.

|

|

Last week Sen. Daniel Akaka said: "Many of the government's records on MIS remained classified, simply for lack of attention. It wasn't until we started to push that the records detailing their achievements were finally released."

The Hawaii Democrat said "military experts agree that the intelligence work of Japanese Americans in the MIS helped bring World War II to an earlier conclusion. Their heroic work undoubtedly saved many soldiers' lives, and their contributions will be remembered throughout history."

Akaka, after being briefed by Sunao Ishio, who in 1994 was president of the Japanese American Veterans Association, drafted legislation that called on the Army to produce a book about the contributions of nisei during World War II.

The Japanese-American linguists translated captured enemy documents, interrogated Japanese prisoners of war, intercepted communications, persuaded Japanese soldiers to surrender, deployed behind enemy lines to collect information and sabotage enemy operations and conducted psychological warfare.

Prior to this assignment McNaughton, who in 1994 was head of the Army's language school in Monterey, Calif., had just completed a $50,000 Army study ordered by Congress under another law authored by Akaka, involving the war records of more than 100 Asian and Pacific Island American soldiers. That review in 2000 resulted in upgrading the Distinguished Service Crosses awarded to 22 Asian-American soldiers, including Sen. Daniel Inouye, to the Medal of Honor.

McNaughton, now the historian for U.S. European Command in Stuttgart, Germany, said the exploits of the Military Intelligence Service were made public at the end of World War II, but were overshadowed by the accomplishments of the nisei soldiers of the 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, one of the most highly decorated Army units in World War II.

Besides the secrecy that surrounded the nisei linguists' wartime intelligence activities, MIS soldiers never operated as an unit, said McNaughton, who received his Ph.D. in European history from Johns Hopkins University. These linguists were assigned to every major military unit and headquarters in the Pacific war.

"The soldiers of the MIS were involved individually in so many campaigns," McNaughton said. "There were 6,000 intelligence specialists who served in companies, divisions and corps and headquarters. Theirs became a forgotten history."

McNaughton, in a telephone interview from his office in Germany, credited Joe Harrington, a retired Navy journalist who in 1979 contacted several hundred nisei linguists and described their wartime efforts in the book "Yankee Samurai," with being the first to publicize the achievements of the MIS.

McNaughton said he saw his job as a historian as "verifying what the veterans said" in books like the "Yankee Samurai" and other publications, which were mainly personal oral histories. "In many cases they were very accurate. In others some of it was exaggerated -- something that old soldiers tend to do."

McNaughton said he completed most of his research, which included interviews with 45 nisei linguists, in 1996.

Then the hardest part began.

"I had to digest it all and put pen to paper," said the retired Army Reserve lieutenant colonel.

"I would do two or three chapters a year," McNaughton added.

Then he would send parts of his manuscript to MIS veterans, like local MIS and 442nd historian Ted Tsukiyama, "to get informal feedback from them."

During those years McNaughton also was transferred to different duty stations.

When he began his research McNaughton was the head historian of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center in California, which is the predecessor to foreign language schools the Army first formed in 1941 at the Presidio.

In 2001 McNaughton was transferred to Fort Shafter and completed the book while in Hawaii. In April 2005 he moved to Europe.

McNaughton said he believes there are exploits of the nisei linguists still to be told and he hopes that their sons and daughters will continue to tell their story.