COURTESY BY TERRY HUNT

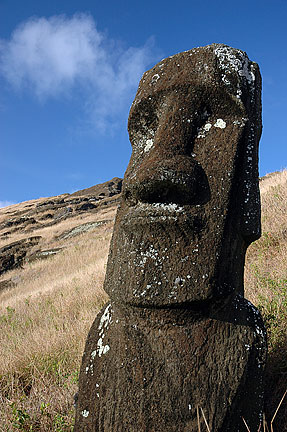

Prehistoric Polynesians on Rapa Nui built gigantic statues, or moai. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

Rats latest culprit in Rapa Nui's demise

A UH researcher disputes that people caused deforestation

Millions of rats, rather than humans, may have caused Easter Island's ecological devastation, suggests a University of Hawaii-Manoa anthropologist.

"The story of Rapa Nui may be mostly about rats," says Terry Hunt, whose findings contradict a belief that prehistoric Polynesians on the island destroyed their ecosystem by building gigantic statues (moai).

In a paper, "Rethinking Easter Island's ecological catastrophe" in the Journal of Archaeological Science, Hunt notes that the small South Pacific island "has become the paragon for prehistoric human induced ecological catastrophe and cultural collapse.

"Scholars offer this story as a parable for our own reckless destruction of the global environment."

Hunt argues, however, that evidence points to rats as the cause of widespread destruction of the island's once-lush subtropical forest and vegetation.

COURTESY BY TERRY HUNT

Terry Hunt, professor of anthropology at UH-Manoa, has led archaeological field schools to Easter Island for the past six years and is going again in July. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

"What we really have to do as scientists is ask the question about contributions made by rats and people," he said in a Star-Bulletin interview.

"So far, researchers and scientists have said people did everything, and there is no evidence in favor of that."

He said data from Rapa Nui, Hawaii and other Pacific islands raises questions about the "simplistic notion of reckless over-exploitation by prehistoric Polynesians, and points to the need for additional research."

Hunt and Don Drake, UH botany professor and specialist on seeds and ecosystems, are planning an international conference on rats and other invasive species March 26-30 on the Manoa campus. About 100 or more worldwide experts in the field are expected, Hunt said.

"What Terry and I both are interested in, and a lot of other people, is how does the presence of rats change the composition of vegetation on islands," Drake said.

Rats didn't exist anywhere in the Pacific until people brought them in, he said. "So plants in Pacific islands didn't face the kind of seed predation that you get with rodents until the last couple thousand years."

Rats may destroy terrestrial ecosystems directly by eating seeds or indirectly by reducing the population of birds that might disperse seeds, pollinate plants or deliver guano from the ocean to fertilize plants, Drake said.

"We're really trying to put the picture in a larger context and understand better what happened in Hawaii and Rapa Nui," said Hunt, who has led UH archaeological field schools to Easter Island each year since 2000. The next one will start July 2.

The team is using new technologies, such as ground-penetrating radar, to analyze subsurface deposits, including buried foundations and statues.

The researchers have developed a large data base listing the location, style details, position and other information on the famous statues. They're looking at the evidence to see how they were moved and what their role was in Rapa Nui society, Hunt said.

Sand dune excavations have provided radiocarbon dates and other evidence showing the island was occupied for a shorter period than was believed, Hunt said.

"We can say the settlement was around 1200 A.D. That's 400 to 800 years later than the previous consensus on the topic."

This indicates rapid deforestation began almost immediately, within 80 to 100 years of the first generation of prehistoric Polynesians, he said.

The human population grew quickly, but the rat population grew much faster, feeding on millions of palms and other trees and shrubs in a dense forest, Hunt said.

"Within two to three years, you can have literally tens of millions of rats. Their numbers double every 47 days."

Rapa Nui was estimated to have about 16 million giant Jubaea palm trees, now extinct, and another species native to Chile, Hunt said. Abundant pollen believed to be from Pritardia palm trees also was found, he said.

The damage rats can do was shown in work done by Stephen Athens of the International Archaeological Research Institute and his colleagues on Oahu's Ewa Plain, Hunt said.

COURTESY BY TERRY HUNT

The team is using new technologies such as ground-penetrating radar to analyze subsurface deposits, including buried foundations and statues. CLICK FOR LARGE

|

|

Their findings show "rapid disappearance of the forest without people," he said.

Hunt's review of Rapa Nui data challenges the picture of the island's ecological death by Jared Diamond, award-winning author, researcher and professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Diamond, who couldn't be reached for comment, wrote in 1995 that the native population "wiped out their forest, drove plants and animals to extinction and saw their complex society spiral into chaos and cannibalism. ... What were they thinking when they cut down the last palm tree?"

Hunt said he finds it hard to believe humans would chop down their last tree, but adds, "We have to ask that question. What rats can do in a sense is more predictable than what humans do. Rats probably will just eat the last seed."

The human population was quite small when the Rapa Nui forest disappeared, so people would have had to be cutting dozens of trees every day to be responsible for the destruction, he said.

No broken adzes were found as evidence of tree chopping, but every palm nut ever found on the island has rat teeth marks, Hunt said. "That's the smoking gun right there. You can see the destruction of future forest in the nuts."

Diamond estimated the prehistoric Rapa Nui population at about 15,000, but Hunt believes it leveled off at 3,000 to 4,000, which would still be high density, he said, with or without a forest.

Also, the population didn't collapse because of deforestation, but because of diseases introduced with arrival of Europeans, said the UH anthropologist.