Trial starts for 4 men for alleged kickbacks

They are accused of rigging airport repair contracts

A group of state officials and contractors conspired to rig construction repair and maintenance contracts at Honolulu Airport, paying $4.8 million to friends and relatives and fostering an environment where kickbacks and political donations were expected.

Federal prosecutors outlined the government's case against two former Honolulu Airport administrators and two contractors who went on trial yesterday in U.S. District Court for conspiracy and 33 counts of mail fraud stemming from an investigation that began more than four years ago by the state attorney general.

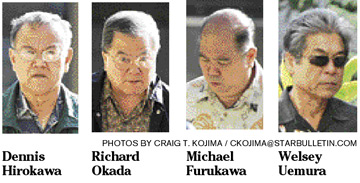

Indicted on federal charges in July 2004 were former airports officials Dennis Hirokawa, 64, and Richard Okada, 65, and contractors Michael Furukawa, 60, and Wesley Uemura, 61.

ACCUSED IN CONTRACTS SCANDAL

Two former Honolulu Airport officials, at left, and two contractors, shown at right, are facing federal charges:

|

Six contractors have since pleaded guilty in Oahu Circuit Court after reaching plea agreements with the state and are expected to testify against the defendants.

Deputy Attorney General Lawrence Goya said the case is about public corruption that grew out of a secret partnership that conspired to obtain public funds for repair work at the airport from July 1997 to June 30, 2002. The mail fraud stems from payments the contractors received via mail for the work that was done.

While others were also implicated, the four men were the main participants, Goya said.

Hirokawa, former superintendent of maintenance, and Okada, director of the airport's visitor information program, are accused of using their positions to secure and award bids to a core group of contractors -- friends and family -- chosen specifically by Hirokawa who were guaranteed that they got the work, Goya said.

Before September 1998, requests for repair or maintenance were sent to the airport maintenance supervisor, who would decide whether the work could be done in-house or had to be sent out to bid.

If the job was less than $25,000, the maintenance engineer would contact three contractors or vendors for bids and the contract would go to the lowest bidder. If the job was more than $25,000, the engineer would follow a more formal bidding process that required public notice and sealed bids. Contracts were awarded to the lowest bidder.

When Hirokawa took over the maintenance supervisor position in September 1998, he essentially eliminated any competition by instructing the maintenance engineer to call a contractor chosen by Hirokawa, Goya said. The contractor would then have to come up with two "complementary" or bogus bids from other contractors or even from another company he was affiliated with just to fulfill the requisite three bids for small-purchase contracts.

"There would be no way he would not get the job," Goya said during opening statements.

Once they had established the contractors they would work with, Hirokawa and Okada approached them about getting something back in return. Usually it came in the form of a kickback or political donations, Goya said.

Okada allegedly encouraged the contractors to take advantage of the situation by raising the amounts they bid on contracts. After learning that they were under investigation, Okada allegedly spoke to Hirokawa and instructed him to tell those who submitted complementary bids to tell investigators that their bids were legitimate, Goya said.

Prosecutors say they don't know what happened to the kickbacks and donations once they were turned over to Okada. A contractor is expected to testify that Okada instructed him to pay in cash only "because it cannot be traced," Goya said.

Attorneys for the defense say their clients are innocent.

They say the contractors who will be called to testify for the prosecution are "admitted thieves" who all worked out deals with the government, have been granted immunity to testify and have much to gain when they are sentenced in state court. They argue that the airport was in disrepair and there was a push to fix it because it was the very first experience visitors would encounter once they arrived and the last when they leave.

Hirokawa was concerned about getting the job done and wasn't out to win any popularity contests, said his attorney, Keith Shigetomi. So when it came time to point fingers, they fingered Hirokawa, Shigetomi said.