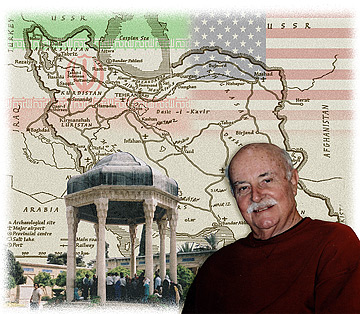

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRYANT FUKUTOMI / BFUKUTOMI@STARBULLETIN.COM /

PHOTOS COURTESY WEBSTER NOLAN AND NAINESH PATEL

Webster Nolan visited the tomb of the 14th-century mystic poet Hafiz in Shiraz, a city in southwestern Iran, seen in this photo illustration.

|

The story on Iran

Suspecting the American media aren't portraying an accurate picture of life inside Iran, a retired Honolulu journalist set out to get a first-hand look at life in the so-called "Axis of Evil" nation

By Webster Nolan

Special to the Star-Bulletin

TWO WEEKS of traveling around Iran earlier this year left me with the impression that at least some Iranians might be just as worried about their leaders as some Americans are about theirs. Admittedly, my impression was thoroughly unscientific and intuitive, based more on the unusual silences that occurred when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's name came up in conversation. Nobody seemed eager to defend him, much less espouse his frequently inflammatory public statements.

My purpose in visiting Iran evolved during the past year or two, mainly because much of mainstream media in the United States and much of the American public seemed to be buying into the idea that Tehran posed a major threat to world peace. It was starting to look like Judith Miller time again, when the star reporter for the New York Times (and her editors) bought into the WMD threat supposedly posed by Saddam Hussein. Only with Iran, it was not just one journalist but many who seem to accept the "axis of evil" rhetoric as fact.

To be sure, there are exceptions (nationally syndicated columnist Trudy Rubin and Washington Post writer David Ignatius come immediately to mind). And plenty of information is available on the Internet and from bookstores and libraries, if one has the time and curiosity to pursue it. Generally speaking, though, the daily coverage about Iran is negative.

Of course, a relatively brief visit to Iran could not prove anything one way or the other. Still, it seemed useful to go talk with some Iranians in their own environment, and also to get a first-hand look at one of the world's oldest cultures. A brief BusinessWeek article last year reported on the growth of middle-class consumerism in Iran, which piqued my curiosity. Also, a well-traveled friend had enjoyed a visit to the country last year and encouraged me to go. So I signed up with a British travel agency, got a visa in London and flew off in late April with 20 other people, mostly Brits, for Tehran. We traveled nearly 2,000 miles, mostly by bus, and the only certain conclusion I came to was that Iran is a terrific place to visit.

For starters, everyone we met was friendly, sometimes going to unexpected lengths to be helpful. (One man actually "walked the extra mile" when, seeing I was lost on a street in Esfahan, he took me to my destination, shook hands and went on his way. Others in my group reported similar experiences.) Another man said he had heard that Hawaii needed more singers to entertain tourists and asked if he could get a job in Waikiki, at which point (this conversation took place in a large crowded hotel lobby) he started singing a Puccini aria to demonstrate his skill. On another occasion, an engineering professor I met recited some lines from the 10th-century epic writer Ferdowsi, a reminder that poetry plays a strong role in the education and culture of Iran.

As a tourist destination, Iran offers hundreds of opportunities to explore and ponder, including some of mankind's most majestic and serene achievements in architecture. On the other hand, much of the terrain we covered was hot, arid desert or rugged mountains without much greenery, which probably explains why Iranians love their public gardens so much. Every town and city we visited had at least one large public park with lots of flowing and fountaining water and beautiful flowers.

PHOTO COURTESY NAINESH PATEL

Webster Nolan poses outside the immense, elaborately tiled gate of the 16th-century Imam Mosque in Esfahan in central Iran, one of the world's most majestic architectural achievements.

|

|

ALL ALONG our route, on the streets, in restaurants, at museums and galleries, mosques and parks, people would start conversations, sometimes to practice their English (taught in nearly all elementary schools), sometimes to sell souvenirs, but mostly just to engage in ordinary conversation, about television programs and movies, cars, sports, our impressions of their country. It was pretty clear that most of them were up to date on global matters, presumably through the Internet.

One of Iran's attractions as a tourist destination is that you can devise an itinerary that generally parallels the chronological narrative of the country's history. That is what our group leaders did. After a visit to several Tehran museums (including the famed jewelry exhibit and the National Museum) on the day of our arrival in the country, we flew south to Shariz and the next day went by bus to the ruins of Pasargardae and Persepolis, the ceremonial palaces of Cyrus and Darius, the sixth-century B.C. "great" emperors who made Persia the world superpower of their era.

Next we traveled through the Zagros Mountains in the southwest, at one point viewing a narrow valley through which Alexander the Great and his army reputedly traveled in their conquest of Iran in 334-330 B.C. Then we visited palace of Shapur I, the shah who defeated the mighty Romans in several major battles and in A.D. 260 captured the Emperor Valerian, believed to have died in his cell at the site.

The Arab conquest of Iran began in A.D. 660, and much of our remaining itinerary focused on that era, which also brought Islam to Iran, and the subsequent centuries of Mongol and Turk invasions, as well the happier years of the Savafid dynasty (A.D. 1491-1722). We visited ancient citadels and caravanserais, old battlegrounds, Zoroastrian fire temples and Muslim mosques, two Armenian churches, mausoleums and madrassas, minarets and medieval bridges, museums and art galleries, bazaars and public gardens.

We stayed in the desert-bordering cities of Kerman and Yazd, and the central Iran metropolis of Esfahan with its extraordinary architecture, before returning to Tehran. Along our route we stopped at smaller towns, Sarvestan and Nairiz, Mahan and Rayin, Natanz and Kashan, each with something special to offer: a delicious lamb stew, a carpet-weaving shop, a centuries-old ice house, a hidden garden, a group of wind towers, an ancient qanat (a remarkable system of wells for irrigating crops and supplying water to towns), and, invariably, some enjoyable conversations with Iranians.

AS OUR JOURNEY progressed and we learned more about the country, we began to fully appreciate that we were visiting a highly energetic, entrepreneurial country. International trade, going back to the Silk Road days and even further, is a major part of their culture, a point made recently in editorial commentaries by former Secretary of State Warren Christopher, who had considerable experience negotiating with the Iranians. In urging resumption of U.S.-Iran dialog, he advises American negotiators to remember that the Iranians are born bargainers, as our own visits to the bazaars amply testified.

Other Iranian assets are its high literacy rate (80 percent, according to a CIA estimate), a growing middle class, citizen experience in election campaigns and voting at the local and national level. A recent study by professors Ali Gheissari and Vali Nasr titled "Democracy in Iran" documents a continuing effort by various political and intellectual leaders during the 20th century to establish rule of law, free press and a more free-wheeling political system than currently imposed. (My own personal experiences also suggest that many Iranians love a good argument, a trait that can play an important part in democracy-building.)

Certainly Iran has some serious problems at this stage in its history. Despite huge revenues from oil and vast untapped natural gas resources, the country's economy is faltering, with high unemployment and inflation afflicting the population, estimated at 70 million. There is a large gap between the few rich and many poor. There are strong restraints on women, the news media and the market economy. The government apparently has a good many inexperienced people in decision-making positions. Students and the jobless occasionally take to the streets to vent their anger. The Iranian president, like the U.S. president, needs to acquire some skills in public diplomacy.

AS WE NEARED the end of our trip, I wondered whether it might be better for our government to work with Iran as a trading partner rather than treat it as a political enemy, as a market rather than a military target, much in the way that we've worked with China during the past 30 years. Both countries would benefit, and a vigorous business relationship likely would help defuse the incendiary rhetoric that emanates from Tehran and Washington.

Getting to that stage would require compromises from both sides, acknowledging past grievances, such as Iran's holding 52 American hostages for 444 days in 1979-80 and the continuing malignant denunciations of Israel. The United States, for its part in re-opening the dialog, would need to acknowledge its role in overthrowing Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953, its stubborn backing of the hated Shah Reza Mohammed, its covert support of Iraq in its 1980s war on Iran, its shooting down of an Iranian airliner in July 1988 with 290 fatalities and its continuing economic sanctions, which in the long run can only hurt and anger the Iranian people. These are difficult and emotional issues, but that is why diplomacy exists -- to recognize such problems and move on toward building better relations.

CURRENT U.S. government concerns about Iran focus on two issues: the suspicion that Tehran is developing nuclear weaponry and that it supports international terrorism. The first step toward resolving these disputes is for both sides to cool down, stop trying to scare everybody with irresponsible public statements. The next step is to find a way to start direct negotiations. That would not solve every problem but could lessen many dangers.

The Internet and a wide range of books and reports offer useful background on these two issues.

On the nuclear controversy, Iran's membership in the nonproliferation treaty (NPT) entitles it to enrich uranium for peaceful purposes. The Web site of the International Atomic Energy Agency affirms that Iran is abiding by the Safeguards Agreement of the treaty, but also complains that Iran fails to cooperate in "confidence building" by refusing to provide certain documents and information about dual-use equipment and certain individuals.

(I suspect that Iran is not the only NPT country withholding information, since no nation would or should disclose data that might help its perceived enemies.)

Still, the U.S. believes Tehran is hiding a nuclear weapons program, though neither Washington nor Israel has provided convincing evidence of this.

Even assuming that Tehran is trying to build a nuclear arsenal, which it denies, the fact that Israel already has such weapons and refuses to join the NPT bolsters Iran's claim to self-defense. But surely there must be a sufficient number of intelligent policy makers and skilled negotiators in this world to come to grips with this problem.

As for Iran's role in world terrorism, it's probably accurate to say that in the early years of the current regime, there was an effort to export the Islamic revolution. But today, when President Bush and his senior advisers accuse Iran of sponsoring international terrorism, they generally give only two examples: supporting Hezbollah's attacks on Israel from Lebanon and Shia militants in Iraq. That's hardly worldwide terrorism. So, again, the first step is to cool the rhetoric and stop frightening people unnecessarily.

Then it might be helpful to look at why Iran helps Hezbollah. In a way, it's similar to the reason why America helps Israel, although the American effort operates on a much larger and more deadly scale. Iran, like most of the Muslim world, works from the premise that Israel is an illegitimate occupier of Palestine that for 60 years has been terrorizing the Palestinians in the name of self-defense. On the other hand, the U.S. government, Democrats and Republicans, has long held that Israel is a legally constituted state that has a right to defend itself from attack, even if, as most recently, it means killing hundreds of innocent people or destroying the economy of a nearby democracy.

This issue is much harder to resolve than the nuclear controversy. My own belief is that the answer probably lies with those 30 or so groups of Israelis and Arabs who work together, mostly in Israel, in village government, in health and cultural projects, and sometimes even at the political level, as in the Geneva Proposal for peace a few years ago.

MEANWHILE, a sincere effort to develop mutually beneficial relations between Iran and the United States seems a far better course than the current saber-rattling. A good place to start might be tourism, especially if Tehran would encourage more Americans to visit by making it easier to get visas. (The visitor destination industry in Iran needs some upgrading, so there might even be a role for Hawaii.) Another step, already suggested by Rubin the columnist, might be to restart cultural exchange programs, with initial emphasis on mutual visits by members of Congress and the Iranian parliament. I might add, as someone who has seen the value of such exchanges, that giving journalists priority might be a big help, sending ours off to Iran and inviting theirs to America.

Webster Nolan is a retired journalist and former director of the East-West Center journalist exchange programs.