ASSOCIATED PRESS / SMITHSONIAN JOURNEYS

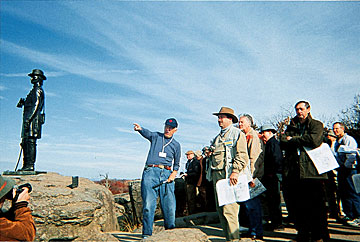

Ed Bearss, in the blue hat, points out over the Gettysburg, Pa., battlefield next to the statue "The Eye of General Warren," while conducting one of his tours. Bearss was recently in Honolulu interpreting World War II for visitors.

|

|

Footsteps to the past

Retired historian Ed Bearss brings his knowledge to Hawaii

HISTORIANS have a thing about dates, even those that don't live in infamy. Ed Bearss clearly remembers Dec. 31, 1972, as the date politics descended on the National Park Service.

The government's best-known military historian was driving from one Civil War battlefield park to another when he heard on the radio that President Nixon had fired NPS Director George Hartzog. Hartzog, it seems, had questioned an illegal yachting lease on federal property held by the brother-in-law of Nixon friend Bebe Rebozo.

"Well!" considered Bearss, while driving. "Interesting times. Hartzog will be a legendary figure because of this."

And there you have it. Ed Bearss, America's foremost interpreter of our military past, in transit between two historical sites and musing on how the future will play.

BURL BURLINGAME / BBURLINGAME@STARBULLETIN.COM

BURL BURLINGAME / BBURLINGAME@STARBULLETIN.COM

"It was a dream, getting paid for doing what I would have done on my own, dealing with visitors and walking in the steps of history."

Ed Bearss

On his employment for the National Park Service

|

As it turned out, in the following eight years, the next three NPS directors were fired as well, and today NPS officials at grades GS-12 and above are required to sign a "loyalty oath" to the White House. As the Park Service is a federal bureaucracy and not an administration asset, it is often forced to run to Congress for cover.

That's not necessarily a bad thing, according to Bearss. "Politicians are so used to trying to appeal to everybody that they can be consensus builders. When you're interpreting a historical site, you want to reach as many citizens as possible. You need the broadest possible scope of interpretation."

Interpretation is the name of the game for Bearss (pronounced "bars"). He is a legend among those interested in history, an indefatigable tour guide to the sacred grounds of America -- particularly Civil War battlefields -- and a walking well of knowledge that decants nuggets out of trivia. Bearss is certainly the only historic-site interpreter to have groupies, folks who are mesmerized by his apparently effortless channeling of the past, not just of dates and facts, but of personality, fate, sheer luck and codes of honor.

BEARSS WAS IN TOWN interpreting World War II for visitors ("The Army is far more cooperative in aiding citizens in the islands than the Navy is," he notes). At 82, a decade after retiring as chief historian of the Park Service, he's still tramping historic sites something like 300 days a year as a tour guide.

"If I'm interested in something, I don't get tired!" he barked, a trademark thunderstorm growl that walks the line between Victorian military mysticism and aw-shucks Americanism. Last month, he was named by the Smithsonian as one of 35 Americans Who Have Made a Difference, a war-wounded ex-corporal in T-shirt and high-water pants who lectures generals and senators on their own turf.

A little history about the historian:

Bearss grew up on an isolated Montana ranch, the E-bar-S, reading books by the light of kerosene lanterns and listening to firsthand Civil War reminisces by a local veteran. He named his favorite milk cow Antietam. When he graduated from high school in 1941, he thumbed around the country visiting Civil War sites and then joined the Marines.

"If I'm interested in something, I don't get tired."

Ed Bearss

Retired National Park Service chief historian who, at 82, still gives tours at historic sites across the nation

In a vicious firefight at Suicide Creek, Cape Gloucester -- the South Pacific, 1944 -- Bearss learned about the value of battlefield terrain the hard way. With both arms shot up, a Japanese bullet in his back and another in his foot, he pushed himself out of the line of fire an inch at a time. Those around him who raised their heads died.

Bearss spent nearly two years recuperating and went to college on the GI Bill. "I got out in '49, got a job at the government hydrographic office and then went back to school again, earning my master's at Indiana University in 1955, my thesis on Confederate Gen. Patrick Cleburne," rumbled Bearss. "While writing it, I made a point of visiting Cleburne's battlefields, walking the land."

On a stop at Shiloh Battlefield, Bearss met a "real live wire" of a National Park Service guide. "Pete Shedd began to talk, and we began to walk, and after 1 1/2 miles, we came to a very deep ravine," Bearss recalled. "Well, sir, I looked down upon that ravine and marveled. I knew the Union forces had a number of cannon situated, but until that moment, I did not 'know' how the land aided their assault. To really understand the full meaning of events, you have to appreciate the lay of the land, the topography of history."

He made a career choice that day. "I learned that the National Park Service employed historians, not just naturalists and archaeologists. There was a vacancy at Vicksburg, and I wound up there. It was a dream, getting paid for doing what I would have done on my own, dealing with visitors and walking in the steps of history."

AT THE TIME, for a government agency, the Park Service was family-size. "About 12,000 employees, 179 units ranging in size from Yellowstone to one acre. Since then," Bearss said, "the service's responsibility has quadrupled in area and doubled in number of units, but the manpower and budget has not appreciably increased."

Preserving and interpreting historic sites is a traditional governmental responsibility, yet the Park Service has to lobby for every preservation dollar -- the knives are out every time Congress gets budget-minded or when the administration is determined to inject political planks into historic preservation.

"In 1969 three bills passed authorizing the establishment of three historic sites honoring three American presidents -- but LBJ was still alive," said Bearss. "That had never been done before, and now it's standard procedure. Of course, there can be no objective review when the ex-president himself is involved. Luckily, all presidents so far have preferred humble sites ... except for FDR."

And Nixon, who so messily injected politics into the process?

"All interpretation on Nixon's site will be done by a board of political appointees, not independent historians," predicted Bearss.

POLITICS ASIDE, the biggest threat to historic sites is unplanned development. Over the past decade, Bearss notes that "development is advancing more irresistibly than Grant's army did on Richmond," citing the demolition of priceless landscape artifacts for tacky strip malls and trailer parks. Bearss has lent his name and prestige to grass-roots patriots across the nation to help preserve their heritage.

The Hawaii Civil War Roundtable hosted a dinner for Bearss while he was here, and dug into their pockets, presenting their hero with more than $1,000 to forward to a battlefield preservation of his choice.

"Franklin, Tennessee!" Bearss boomed, gravel in his voice, a direct channel to the past. "I was present in Franklin two weeks ago, lucky to be an honored guest. I was given the privilege of finally swinging a sledgehammer on that most detested of battlefield intrusions -- the Pizza Hut. Down it went! It was a bitterly cold day, and the Tennessee re-enactors had no shoes upon their feet, bless 'em. As they marched by the rubble, they shouted, 'Huzzah, hooray! Next, Dominos!'"