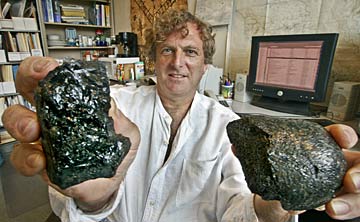

DENNIS ODA / DODA@STARBULLETIN.COM

UH geologist Ken Rubin displays some undersea volcanic rock samples that do not show the erosive dullness of age. Rubin led research that has restated the age of rock in mid-ocean volcanic ridges, from thousands of years to less than 100.

|

|

Study revises view of ocean volcanoes

Rocks formed by underwater volcanoes are much younger than believed, indicating eruptions are more frequent than suspected, researchers led by a University of Hawaii-Manoa scientist have discovered.

Researchers had thought it took a few thousand years for rocks to form in the deep ocean, "but we know for most rocks we studied, it has to be" less, said Ken Rubin, geologist-geophysicist at the UH School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. "We're talking about a handful of decades for most of these rocks."

Rubin's team used natural radioactive isotopes in young lava flows on the sea floor to model how long it takes for rock to melt and rise from beneath the Earth's crust to where it solidifies and builds up at the deep-sea ridge. The research shows rocks could be formed in about 100 years.

Their study was reported in the recent issue of the journal Nature.

Rubin said they started the project to determine the age of mid-ocean ridge basalts.

"We expected to find the opposite signature of what we found, and when we didn't, and when we went through all the possible ways to try to explain what we found, the only way we could explain it was in the mantle during melting."

He said this led to "a cascade of implications" about the length of time for rocks to percolate up from the mantle -- the layer between the Earth's crust and core -- and the time they spend in the crust, which "became shorter than people thought.

"Melts migrate very, very quickly up the mantle from the depths where they erupt," Rubin said, adding that magma may rise as much as six miles a year.

The findings suggest that mid-ocean volcanoes are erupting more often than believed, with rapidly fluctuating geological, biological and chemical conditions allowing unusual biological communities on the sea floor to thrive, Rubin said.

"The ocean ridge system supports some of the most unique, and perhaps most ancient, habitats on Earth, where highly localized communities thrive on chemical energy from volcanically driven hydrothermal circulation, rather than converting light energy from the sun," he said.

Deep-sea biological communities, noted for such strange creatures as tubeworms that stand upright in long tubes, can migrate along the ridge from one eruption to another to take advantage of favorable conditions, Rubin said.

With the new findings, he said, scientists have to rethink what they know about the Earth's mantle -- "not so much what it's composed of, but its physical properties."

All sites studied by Rubin's group were in the Pacific Ocean, including the spreading East Pacific Rise, Juan De Fuca Ridge in the northeast Pacific and Loihi Seamount near the Big Island.

Samples were collected with remotely operated vehicles and submersibles of the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory and Woods Hole Ocean Oceanographic Institution.

Rubin said all the rocks came from collaborations with UH geologist-geophysicist John Sinton and Rodey Batiza, formerly at UH and now with the National Science Foundation, who led expeditions.