A simple pot of rice is especially satisfying after the cook works up an appetite by harvesting the precious grains by hand

By Joan Namkoong

Special to the Star-Bulletin

This is a story about a craft project that ran amok. But it became a lesson about food processing that taught me to appreciate that bag of rice in the supermarket.

Last April, the Honolulu Academy of Arts hosted an exhibit, "The Art of Rice."� Several water-filled planter boxes were sown with rice to add to the ambience of the culturally rich exhibit. There they were, green sheaths of grass-like plants, bearing grains of rice, a crop once grown in Hawaii in places such as Hanalei Valley, Kauai and Waikiki.

|

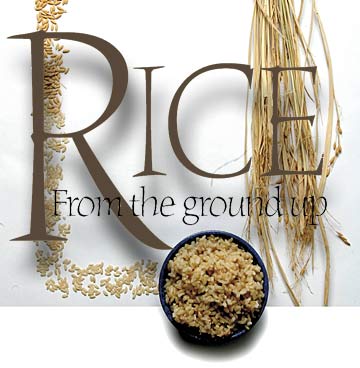

Above photo: The various stages of rice, counter-clockwise from far right, rice straw, unhulled rice grains, hulled rice grains and, finally, cooked rice. Picture by Dennis Oda, doda@starbulletin.com

|

At the close of the exhibit, I asked for some of the rice straw, thinking I would try to weave a basket or something from the dried stalks. I received several bundles of dried straw, with rice grains still attached.

Well, perhaps I should harvest� the rice first, I thought. How wonderful it would be to eat some fresh, Hawaii-grown rice.

I remembered reading about the hand harvest of rice and the process of threshing, separating grains from stalk. Then the rice has to be cleaned of any remaining straw and chaff, relying on wind power to do that work.

After several days of drying in the sun, the rice can be stored or hulled, polished, graded and bagged. I recalled photographs I'd seen of people in Asia, beating bundles of rice stalks on the ground and how the wind would carry away the hulls as the rice was tossed in winnowing baskets.

Quickly realizing that you'd have to beat very hard to get the grains off the stalks, I proceeded to strip the grains by hand. I guess I could have driven my car over the stalks several times, another method sometimes used to thresh (that's the name of the process of separating the grains from the straw). After a couple of hours of hand-threshing, I had a few pounds of rice -- but the brown grains had bits of straw and dust mixed in.

It was a breezy day, so I took the rice out on my condo lanai. I grabbed handfuls of rice and let them fall back into the pan, allowing the wind to carry away the unwanted particles -- against house rules, of course. Another couple of hours later, I still had a few bits of straw in the pan of rice, at this stage known as paddy rice. By then I was trying to figure out the next step.

As I examined individual grains, I realized that the outer hull had to be removed and that was not going to be easy. Piercing the hulls with a fingernail was going to be a very slow process. Perhaps drying it a little would help. I was right: After several days of sun on my lanai, the hulls did separate from the grains easier, but hull removal would still require some effort.

DENNIS ODA / DODA@STARBULLETIN.COM

A mortar and pestle was used to separate the hulls from the grains of rice.

|

|

Mortar and pestle, perhaps? An old-fashioned method, but it worked. On most of the grains, that is. Some stubborn hulls remained attached. Pound more and you break the grains. I wondered how it's really done.

I called Karol Haraguchi of Hanalei, Kauai, to ask how rice was processed on her family farm, now converted to taro fields. Rice was hand-cut, Karol explained, then horses would walk over the straw to remove the grains.

Later, the family acquired machines powered by a diesel engine that accomplished the threshing and other steps. One of those machines was a huller, designed to separate the hulls from the grains with a blower that sucked out the hulls and dust, leaving grains of edible rice.

A hulling machine was not in the realm of possibility for me. So I persisted, a tablespoon or two at a time, gently pounding/grinding the grains in my wooden mortar and pestle, trying to coerce the hulls from the edible rice. Eventually I had about two cups worth of grains and hulls, separated and not. It was time to get rid of the hulls.

I set up a small electric fan next to my kitchen sink. I dropped handfuls of rice in front of the fan so that the hulls could be blown into the sink and the grains would be caught in a bowl below. Several passes in front of the fan were needed. What a mess: tiny airborne hulls and dust everywhere in the kitchen.

And I still had hulls attached to the rice. The only way to complete the process was to pick the hulls off one by one, using a fingernail to break each stubborn hull and peel it away.

Many hours later, I had about a cup's worth of edible rice -- a light tan-colored rice, what is known as brown rice. To get white rice would require polishing, a process I knew I could not accomplish.

Into the rice pot went the rice. Just a brief rinse and on went the rice cooker. Yes, I enjoyed every fresh morsel, fully understanding how much effort goes into getting rice from the ground to the table.

I still have a couple of pounds of paddy rice, waiting to be hulled. But for my rice supply, I'll head to the supermarket and buy a bag of rice, polished and ready to cook. Most of the rice in our markets is from California, and starting this month, there will be bags bearing the words "new crop," indicating the contents were harvested just weeks ago.

It's the freshest rice you can buy and worth every penny.

Now, for me, it's time to go back to the craft project.