|

Gathering Place

|

Let’s forget about

the Akaka Bill

Late one Friday night in early 1998 in Washington, D.C., as I attempted to close up my research in the National Archives on America's annexation of Hawaii, I stumbled across a file generated by the U.S. Navy. It was located around 1900, just two years after the annexation, at a time of the gray transition between the Sanford Dole government and the imposition of a purely colonial government onto Hawaii.

With alarm it described prominent annexationists in Hawaii pilfering lands from the misnamed "ceded" lands that had been taken over by the U.S. government. I rubbed my eyes. I thought I must continue my research in this vein -- extending beyond 1898. But then I thought, "No, go home. Get to recording what you've got (the research that became the book and film 'Nation Within'). This is for another time, probably for another person, when the Hawaiians gain a mechanism for pursuing their court claims."

Now that the Akaka Bill is closing the door on court claims, that moment in the archives comes back to me with a terrible thud. Will there be no reckoning of Hawaiian land claims? No day in court? No justice?

As a community, let us struggle to be honest with ourselves. The answers to these questions are no, no and no -- not if the Akaka Bill as now amended becomes law.

The resource focus of the contemporary Hawaiian movement from day one was land. Specifically, it was the land set aside at the time of the Mahele for the monarch and for the administration of government. This focus was quite nice and quite politic of awakened Hawaiians, since it limited the potential for friction considerably. They weren't going after my house lot or yours or Costco's, but only making claim to -- or seeking back rent on -- lands now curiously held by the state government of Hawaii as well as those grabbed by the U.S. government.

Prior to that particular Friday night, I had had the opportunity to examine the documents leading up to and resulting in Hawaii becoming an overseas colony of the United States. These documents substantiate the argument that Hawaii was never legally taken in to the United States.

The stark facts are clear for all to see: The "revolution" of Lorrin Thurston's fevered imaginings was a coup d'etat backed by U.S. troops and orchestrated by Washington. The republic that Dole sanitized was an anti-Republic engaged in systematically denying Hawaiians of their rights (and also engaged in terror to back up their position).

The Hawaiian people massively protested against the takeover. They repeatedly demanded and were always denied a vote on the question, which many individuals of the fraudulent republic conceded would be a "no" vote -- no annexation. The most essential feature of a democracy, government by consent of the governed, was denied.

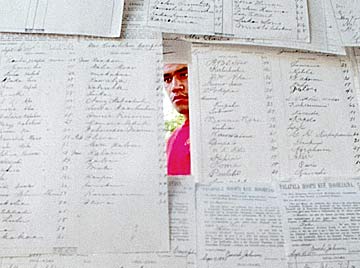

I was clued by the Hawaiian scholar Noenoe Silva to the location of the Hawaiian petitions against annexation. The files had been carelessly folded and stuffed into boxes. I held them in my hands, page after page, file after file. The edges of some of these 100-year-old papers crumbled and fell off. They had not yet been elevated to important and endangered material, nor had they been duplicated as traveling exhibits, which Hawaiians approached with drawn breath to find the names of their grandparents and great-grandparents. All the names are there.

Kekoa Kahele looks over copies of the petitions to protest the annexation of Hawaii a century ago.

That Friday night, the Navy's record of concern for the pilfering of lands from the U.S. government was only one more layer of irony. It was a matter of petty theft within grand theft. Surely, I thought, if only the truth could get out there would be a process for cleaning up such a mess.

What became the Akaka Bill evolved. What began as an attempt at limited self-government coupled to reconciliation became self-defense against the small elite band who are savagely pursuing Hawaiian assets in the name of -- of all things -- civil rights. (The civil rights of poor downtrodden white people!)

Along the way, those concerned with enrolling their children in Kamehameha Schools (with whom I empathize -- my oldest son graduated from there) have become increasingly at odds with those Hawaiian nationalists who cling to the view that the entire thing was illegal, that Hawaiians never gave up their sovereignty and that the Akaka Bill will build a federal lei stand, where proud people will string flowers.

Viewed with some mixture of objectivity and compassion, the Akaka Bill is a classic case of indigenous people being divided over how to respond to their colonizers. As a defense against the lawsuits, the Akaka Bill was hard to oppose. There were strong suggestions (as in the Kamehameha Schools 9th Circuit Court ruling) that once in place, federal recognition would insulate Hawaiians against suits (as in the fact that institutions of indigenous people do not, by definition, violate the civil rights of the larger society). Those feisty Hawaiian intellectuals -- Kekuni Blaisdell , Jon Osorio, Noenoe -- might argue that the Akaka Bill was really about quashing Hawaiian land claims for all time, but what could they tell the poor mother or father who modestly hoped that their child would find a slot at Kamehameha Schools?

As President Bush and the Senate Republicans show their hand through amendments of the Akaka Bill, it is the hand of rapacious imperialism essentially unchanged from a century ago. Would Hawaiians like to be recognized as an indigenous people? No problem. They need only set aside their land claims. They need only set aside history. In fact, let us all forget history. Let us wallow in American jingoism and stand shoulder to shoulder, dispatching our children of mixed ancestry to wars of ever more distant conquests.

A ole. This is too much. I empathize with Senators Inouye and Akaka in their well-meant efforts, but with respect I suggest they have become fixated on getting a bill out. If giving up just claims is the price of the bill, let us forget the bill. Let us preserve some measure of respect for one another and not become accomplices to another fraud. Let us come home to Hawaii and hunker down. Let us rally around the Hawaiians, and denounce their tormenters for what they are, and live to fight another day for some semblance of real justice.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]