|

In-vitro

breakthrough

A UH discovery raises hopes of better

pregnancy rates following sperm injection

Couples trying to have babies through a sperm injection in-vitro treatment might have more success because of a discovery by University of Hawaii researchers.

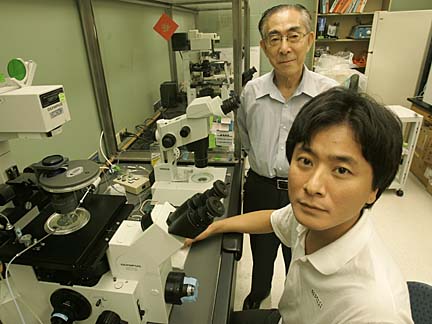

Working with mice, Ryuzo Yanagimachi and Kazuto Morozumi found that intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), a common method of in-vitro fertilization, might be hazardous to developing an embryo. But they discovered that a change to the procedure could increase the success rate.

Removing the acrosome, a caplike structure covering the sperm's head, before sperm injection, could result in more babies for people and animals, the scientists concluded.

The findings of Yanagimachi, a professor of anatomy and reproductive biology who pioneered cloning of mice in 1998, and Morozumi, an obstetrician/gynecologist from Japan, were published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Discussing their findings in an interview, they said the ICSI method is an effective way to overcome certain types of male infertility.

While millions of sperm are needed to achieve normal fertilization, the injection technique requires only one sperm for one egg, they said.

|

Yanagimachi showed the ICSI method could work in hamsters in 1976 and applied it to other animals after it was used successfully in 1992 to produce human babies.

Although it is largely successful, he said he and Morozumi found the production rate might be improved by removing the acrosome, a caplike structure covering the sperm's head, before the injection.

The acrosome can be removed easily and quickly with a chemical or mild detergent, Yanagimachi said.

Enzymes in the acrosome help the sperm penetrate the outer membrane of an unfertilized egg (oocyte) in a natural fertilization process, but the acrosome itself never enters the egg, the researchers explained.

In the fertility treatment, sperm with acrosomes are injected directly into the eggs.

"It is rather amazing that the eggs tolerate the enzymes and develop into an apparently normal offspring," Yanagimachi said.

However, he said, some scientists have speculated that the acrosome could damage a developing embryo if injected.

Morozumi said only 30 percent of eggs injected with human sperm develop successfully, and only 40 percent of women undergoing the procedure go home with babies.

In their investigation, Yanagimachi and Morozumi injected sperm with and without acrosomes into unfertilized mouse eggs.

They found that sperm cells with intact acrosomes caused significant damage and sometimes death to the eggs. They said the damaging effects appear to be due to the enzymes.

Yanagimachi said ICSI success rates have not been high for animals because sperm of some animal species have very large acrosomes, and injection of such sperm could kill the egg.

"Fortune has smiled on human ICSI," he said, explaining that human eggs are relatively large (about one-tenth of 1 millimeter), and a human sperm cell has a small acrosome.

"If the human egg was much smaller or the sperm had large acrosomes, ICSI in humans could have been problematic from its inception," Yanagimachi said.

Still, only four out of 10 couples have babies when injected with sperm with acrosomes, Morozumi said.

Morozumi has worked the past year at the UH Institute of Biogenesis Research, headed by Yanagimachi in the John A. Burns School of Medicine.

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]