Maunawili Elementary principal

|

DOE moves to

standards-based

report cards

The new grading system

goes into much greater detail

about academic progress

Move over A, B, C, D and F.

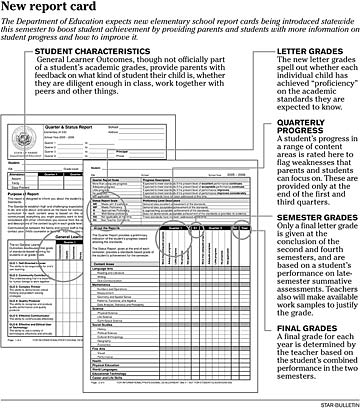

When the state begins issuing new standards-based report cards for elementary schools next month, it will spell the end of that familiar grade scale and signal a new era featuring its odd-sounding successors ME, MP, N and U.

But the switch goes much deeper than the image of a student bursting through the front door announcing, "Mom! I got an ME!"

What is a standard?

Hawaii public school children are expected to know and be able to do certain things by the end of each semester. Each of these things is called a standard. Under a new standards-based report card this year, teachers must determine whether students "meet," "approach" or fall "well below" proficiency in the standards for their grade level.

Example of a reading standard: "Students must be able to respond to texts from a range of stances: initial understanding, personal, interpretive and critical. This means that by the end of the third grade, students should be able to:

» Relate information and events in written material to their own ideas and life experiences.

» State the important ideas from a reading and identify a theme or generalization. » Interpret written material in a variety of ways (e.g., writing drama, art, media)." Source: Department of Education

|

Grades will no longer represent an average of a semester's homework and test scores, but will be based on what a child knows and can do by semester's end.

As such, homework and quizzes will cease to be a part of a student's official academic grade, but will be viewed as "practice" toward the end-of-term goal.

"It's a pretty big change in thinking because people are so used to the old way and it's probably going to take a long time for some of them to adjust," said Arlyne Yonemoto, principal of Maunawili Elementary, one of 10 schools that have piloted the new grading system over the past two years.

Department officials say the change is necessary to bring grading in line with a switch several years ago to a standards-based education system. A growing trend nationwide, the system establishes a uniform set of academic expectations, or "standards," across the state and his been shown to improve student achievement.

It also abandons any use of a grading curve, which essentially compares students to each other, and avoids meting out potentially demoralizing grades like scarlet letters early in a semester. Instead, each student will be judged only on whether they have learned what they should by semester's end.

For example, under the old "grade averaging" system, a student might start out a semester poorly with Ds and Fs. But in mid-semester she hits her stride, and gets straight As down the homestretch. In her mind, she mastered everything, but once all her schoolwork is averaged out, she gets only a C.

That's like penalizing a sports team's win-loss record after a bad practice, said Ronnie Tiffany-Kinder, a Maunawili Elementary teacher.

"The grading needs to reflect the learning and the progress a student makes, not pigeonhole them from the start," she said.

Under the new system, teachers will judge students based on whether they meet "proficiency" in each standard through school projects or tests aimed at gauging their abilities. Final grades are "meets with excellence" (ME), "meets proficiency" (MP), "approaches" (N) and "well below" (U).

To keep kids on track for an ME, detailed information will be provided each quarter on how much progress kids are making.

"The idea is to get children to think more about their own education, where they're headed and how to get where they want to go," said Robert Widhalm, who is coordinating the department's introduction of the report card.

Students don't get a free pass on studying. Though not part of the final grade, parents can see how their kids are rated on homework and what kind of student they are in a separate section titled General Learner Outcomes.

Additional pages include specific teacher comments, as well as opportunities for parents and even students to weigh in.

"It's a lot to digest, but it shows you the weak areas and help you to communicate with the teacher on what to do," said Calvin Nekonishi, grandfather of three Kaneohe Elementary students, after glimpsing the new format.

"If a kid is given an F in the first quarter, they might just give up, so this is good," he said.

But some parents say the change raises many concerns, as well.

"I hate it. I really do," said Aina Haina Elementary parent Maria Harbert. "When you really look at it, it either says you're meeting proficiency or you aren't and I don't think that's fair. There's no middle ground."

Others view the card as another example of edu-jargon run amuck in a department that routinely tosses around words like "rubric."

"If A means the same thing as ME, then why bother with all this?" asked James Gangiarra, another Aina Haina parent, who also sees problems with the focus on test-taking.

"It doesn't really reward a child for doing their homework every night. He may be great at homework, but if he's a poor test-taker, he'll get a grade he doesn't really deserve," he said, adding that students will be "toast" when they get to college if they aren't forced to build strong study habits.

The department's view is that the General Learner Outcomes, though merely supplemental information, should serve to keep children honest. Teachers also believe the more gentle grading approach and the extra information will prompt students to take more "ownership" of their education.

"One of the surprising things for me was that my students seemed a little more interested in their learning and less interested in 'what is my grade?' -- which is exactly what we want,'" said Maunawili's Tiffany-Kinder.

However, she and other teachers say that without the hard scores on homework and quizzes to go by, standards-based grading depends on judgment calls by teachers, raising the risk that some teachers might judge their kids more stringently than others.

"If one school doesn't hold their students to the same high standards as another, that's not fair. That's one of the biggest challenges that needs to be worked out," she said.

Figuring it all out means more work for teachers already swamped by federal and state demands to raise student performance, said Theresa Ohashi, a third-grade teacher at Helemano Elementary.

"It's going to involve a total mindset change in the way you keep your grade book and I don't think people really understand how much more work that is for us," Ohashi said, though she supports the overall intent of the change.

Tiffany-Kinder said she determined her student's grades either on late-semester tests, large projects that put many standards to the test or a combination of both. But she said vague guidelines could test the abilities of many teachers.

"This is going to require a lot of training and support and a lot of study by teachers into 'how do we do this?'" she said.

The department has issued general guidelines, but Widhalm said additional training is being handled at the individual school level and there are no plans for a statewide effort.

It also remains unclear how the report cards will affect such things as transfer to private schools. Most private schools say have not yet seen the new report cards, but some say the new system might actually be better for them.

"We've had to deal with all kinds of report cards in the past anyway and this one may actually give us more info to go on. It might just take us longer to decipher," said Pat Liu, Iolani School admissions director.

Secondary public schools will deal with similar issues in the coming years, when the Department of Education introduces standards-based reports cards for middle and high schools.

Widhalm said the department is still unsure how those will look due to concern over how colleges will receive them, but a hybrid version that retains the ABCDF scale is one possibility.

"Then what's the point?" asked Harbert. "It shows that this hasn't been thought through."

Regardless of how it affects everyone else, Tiffany-Kinder said the good of Hawaii's students should be paramount.

"I'm not saying this is perfect," she said. "We're still transitioning to this, but it's a move in the right direction."

|

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]