Unemployment

drops to 2.6%

The state's economy has added

22,250 jobs in the past year

Workers can demand higher wages

Hawaii's unemployment rate dropped to its lowest in almost 15 years last month, as key industries that have driven job growth maintained high worker levels or continued to grow.

![]()

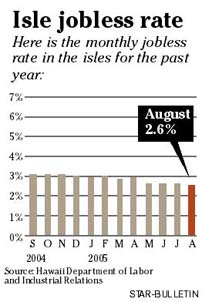

"This continues this pattern of strong employment growth that has kept the unemployment rate at low levels over the past year," said Byron Gangnes, a University of Hawaii economist. "We've been 2.7 percent or below since May."

The 2.6 percent rate in August was the lowest since May 1991.

Altogether, 619,700 workers were employed in August, the Hawaii Department of Labor and Industrial Relations reported yesterday. That was 2,600 more than were employed in July and 22,250 more than in August 2004.

Meanwhile, the number of unemployed workers declined to 16,800 in August from 17,150 in July and 19,150 last August.

Gangnes said the trend was the hallmark of a strong economy: As demand for workers in a region grows, it attracts not only workers migrating from other places, but also locals who previously had not been looking for work and were not considered part of the work force.

"In good times you don't have people throwing up their hands and watching soap operas instead" of looking for jobs, Gangnes said.

State officials are trying to seize the moment to train existing workers for better-paying jobs and provide educational opportunities for those without access to them. For example, James Hardway, special assistant to the state labor director, said the agency has secured a $2 million grant to train people to be certified nursing assistants and is seeking money for a pilot project to provide online education programs for single mothers.

Driving August's strong numbers were the government sector, which added 1,200 jobs during the month; trade, transportation and utilities, which added 550 jobs; professional and business services, which added 400; and leisure and hospitality, which added 100.

Although the construction industry saw a loss of 300 jobs, from 32,800 in July to 32,500 in August, construction firms still had 2,500 more workers than in August 2004.

In any case, the decline in construction jobs didn't seem to make it much easier for employers to find skilled workers, such as carpenters, who have been in short supply amidst the islands' construction boom.

Annette Lyons, human resources director for Sea Life Park in Waimanalo, said she simply can't find a carpenter to do maintenance at the theme park.

"We've been trying to find a carpenter, but most of them are coming in and asking for $27 to $30 an hour," she said.

Equally daunting has been the hunt for a plumber, a director of sales and a part-time information technology specialist, Lyons said.

"It's just so hard to keep people," Lyons said. "Before, I used to have people with longevity. Now you're lucky to have them three months. I think it's just because there are so many choices out there."

The upside of this is that workers can demand higher wages, Gangnes said, which can help them improve their standard of living in a high-cost state not known for rapid wage gains. Nonetheless, Gangnes said, the specter of wage inflation combined with rising costs of energy and building materials could spell the end of the development boom that has been fueling Hawaii's turbocharged economy.

"We expect as we move forward those pressures are going to start to slow the growth in Hawaii," Gangnes said.

But precisely when this will happen is anyone's guess.

"I can't go out there and put my hand on a date or time or year when that tipping point occurs," said B.J. Kobayashi, president and chief executive of the development firm Kobayashi Group LLC.

"Are we at that point? No, obviously, because we are continuing to develop products, as are our competitors," Kobayashi said. "Are we getting to that point? Maybe."

The rebuilding effort following Hurricane Katrina is almost certain to pull workers and building material to the South, which will hardly help Hawaii developers already facing tight markets, Kobayashi said.

His company is developing the 394-unit Capitol Place residential project downtown, the 248-unit Hokua condominium project on Ala Moana and the Kukio Golf & Beach Club on the Big Island, which includes two golf courses and 375 homes. And he sees no decline in demand.

"We let the market tell us when to stop," Kobayashi said. "And it's not telling us to stop."

E-mail to Business Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]