|

Hollywood Drop Out

Jason Scott Lee forsakes the

glamour life for a rain-forest home

on the Big Island with no power,

water or flush toilet

Volcano, Big Island » A half-dozen years ago, Jason Scott Lee was in Florida playing the studio publicity game -- sitting for interviews and photographs to promote a new film.

After a day of interviews, the Pearl City High School graduate had dinner with friends. Conversations floated about careers, Hawaii, lifestyle. An actress at the table talked a lot about money, fame and her latest acquisition, a $90,000 Mercedes Benz.

In contrast, Lee said he was working to simplify his life.

"I want to work when I want to, on films that I want to, and not have to pay for a lifestyle that doesn't do anything except obligate me to the machine," he said.

The dinner party went quiet. Then Lee continued, mentioning work he'd be turning down: "Too disruptive to what I want to do and where I want to be."

"You're nuts!" the actress said. "Your brain must be getting moldy up there on the volcano."

"Probably," Lee said, laughing.

In the early '90s, Lee was the wonder boy of Asian-American actors, wowing audiences with his emotional intensity and physical power in many quality roles. He was an Inuit Eskimo ("Map of the Human Heart"), a Polynesian prince ("Rapa Nui"), an Indian wild boy ("Jungle Book") and an icon ("Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story"). He had five bona fide romantic leads, a major achievement for an Asian actor in Hollywood.

Lee loves acting. But even more, he has another dream: He wants to leave his mark other than on the stage or screen.

Jason Scott Lee catches up on phone calls at his Volcano Village home on the Big Island. The only electricity in the rustic home comes from a 12-volt battery. A solar panel powers a water pump, and a propane tank heats the water. Cooking is done on a wood-burning stove; bathing, in an old horse trough.

Life here is borderline ascetic, especially for a movie star, but Lee lives it most of the year.

Part of his dream was having his family -- mom Sylvia, three brothers and a sister -- move from Oahu to the Volcano property.

"I thought we could all live a very simple existence -- a clean, healthy life -- and my family could all have a house on the property, share in duties," Lee says. "But I realize not everyone wants country life, and my family wants to live their own lifestyles."

But for himself, Lee found a new, more fulfilling path. Turning his back on Hollywood -- he dropped his manager and agent -- he focused on yet another dream: to build a small performing arts venue for professional-quality, socially conscious plays, workshops and classes. He also hoped to have cast members and instructors live there with him.

Pu Mu, the name Lee has given his compound, means "simplicity" and "nothingness." Through it, Lee lives his strongly held environmental beliefs: responsible farming, eat what you grow, an emotional and spiritual connection to agriculture and culture, ecological stewardship.

After weeks of auditions, Lee gathered three like-minded actors in the compound for his first production. Since early June they have helped farm about four acres of the land. Their play, "Burn This," debuted last weekend.

Lee says his real focus is to repair the deforested areas of his property. "I want to bring the canopy back."

So he searches the forest for koa seeds, replanting the fast-growing trees at Pu Mu. "Koa reforestation is not hard; one tree will make a dozen keikis," he says. "And taro grows wild under the canopy. You don't have to open the forest up and till it and mulch it to make it work."

Lee tends to his taro. He farms using natural methods developed by Japanese agrarian Masanobu Fukuoka.

Fukuoka uses no tilling or chemicals, incorporating and controlling useful weeds rather than eradicating them. On Lee's land, weeds grow alongside taro, "challenging" the Hawaiian staple to grow strong and survive.

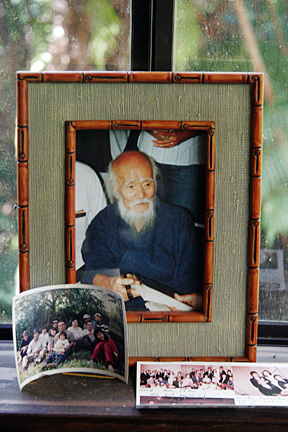

A weathered photo of the elderly, white-haired sensei sits on a shelf in Lee's house. Lee holds it like a priceless, fragile relic.

"A friend of mine gave me his book, and I was very inspired by it," he says.

Lee returns the photo to its place, near a mattress that sits on a Tibetan rug. A nearby makeshift desk is stacked with papers and a phone. The home has no computer or television because the only electricity in Lee's house is provided by a 12-volt battery.

"People say your eyes go bad if you read by candlelight," he says. "Not true. I have 20-20 vision."

A tiny room holds the horse water trough that Lee uses for a bathtub. A single solar panel operates a water pump, and a 5-gallon propane tank heats water for bathing.

"Local style," Lee says. "Wet down, scrub down, rinse." Then he asks, "Want to see a real lua?"

An elevated walkway leads 20 feet into the forest, where an outhouse sits above the ground.

The monklike accommodations beg the question, Is Lee lonely here?

"Sometimes but not lately, with all the projects that I have," he says. "When you're working and feeling achy and have to get up because no one is going to do something for you, that's tough. But it's yin and yang, and builds strength of character."

Lee keeps Fukuoka's photograph on a shelf near his bed.

His forearms and hands are so toned they look like fine tools. He has a sculpted face, widely set eyes and a flawless nose. From each of its wings, a curved line descends to enclose his lips, almost like parentheses.

Lee's manner is friendly, direct but measuring. He is very vigilant.

For his film work, Lee chooses projects that have some significance while providing the income he needs to maintain Pu Mu. Perhaps the biggest difference between the 25-year-old actor of "Map of the Human Heart" and the man today is his insistence on remaining uncorrupted by material ambitions, his almost childlike responsiveness to joy.

Lee credits his mother and late father Robert as "very, very influential."

"My mother's compassion and my father's tenacity were two things that combined in me," he says. "The compassionate side is where all the environmental interest is, wanting to contribute to the community, and not taking myself too seriously."

Bob Lee was tenacious about his son spending wisely, but early in his burgeoning career, Lee admits he "dabbled on wine, woman and song."

Eventually, something in Lee screamed to slow down. "I've always had this ability to get introspective, be more thoughtful," he says.

"I've saved a lot of money, but this lifestyle does keep you in a low overhead."

In 2003 and 2004, Lee spent several months in Kazakhstan filming the government-funded historic epic "Nomad," in which he plays the adviser to a future king.

Lee also chooses film projects "for kokua," such as Lane Nishikawa's new motion picture, "Only the Brave," about the 442nd World War II combat regiment.

"I'm not one to perpetuate a war story, but the story of those people in the 442 caught in that situation is pretty incredible," Lee says.

Lee insists he didn't reject Hollywood, but just found his true self.

"For some people in Hollywood, their soul dies. You're dependent on so many things: recognition so you can get the next job ... the next movie to pay off your big house and your big car. It's a choice."

Lee laughs at his situation, "one foot in Hollywood and the other in a jungle."

"This right here," he says, touching a koa sprout, "is the world that allows me to stand the other one -- because Hollywood really doesn't mean nothing," he says. "I do some film work, then come back home to grow the kala, fish, read, weed and now prepare for rehearsal in my theater.

"My life is pretty complete at Pu Mu."

E-mail to Features Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]