|

Glanville’s promise

How going to Iraq and meeting "the

greatest generation in the history of

the world" led former NFL coach

Jerry Glanville to the Hawaii sideline

HE DOESN'T KNOW their names. Not yet, but that doesn't matter. He knows them. They're the reason. They're why he's out here again, after all these years, out on the grass, directing defenses in a warm rain. Calling them by jersey numbers, the thrill of it all coming through in the tone of his voice. Retirement? Time away from the game? Gone now. He jogs after practice in the morning sun.

This is the mission. This was the promise.

The first thing he did when he got back was sit at the phone and call families, one after another, something like 70 a night. He had the numbers right there, had the messages, had the names.

You can just tell people sit there, waiting for that phone.

And so he knew to be careful. Don't worry, he would say. It's OK. Your son/father/husband/ daughter is fine.

This is the first thing he did.

"I was just with him," he would say.

He could still see all those faces. Still can. All those eyes are still with him, in quiet moments and in his dreams.

"That's why I'm here," Jerry Glanville says hoarsely, at the University of Hawaii's next-to-last football practice of the spring.

There are tears behind his shades.

LIKE SO MANY of life's great revelations, this one came in the can. This was in a long convoy in the desert dust of the Middle East. This was when an officer urged him not to let opportunity slip away, and so he hit the last-chance latrine and shut the door.

And there, in magic marker on the wall, were words that kicked Jerry Glanville right in his heart:

"I'd rather live one year with the lions than a thousand with the lambs." Signed: "The American Soldier."

How to explain why this bumper-sticker-sounding slogan could shake him so? How to describe the context to someone who wasn't there? How is it that those who set out to inspire always end up on the floor looking up, realizing the roles have been reversed?

Those words on the wall slammed him.

"And the whole trip was like that," Glanville says.

This was in March 2004, when he and eight others went on a weeklong NFL Alumni Association trip to Kuwait and Iraq, traveling to three, four camps a day, all day, late into the night. Visiting thousands of young United States servicemen, seeing them operate under pressure in the field in the middle of a war.

Outdoorsman Bud Grant dropped a fishing line in the waters around one of Saddam Hussein's palaces on that trip. Tough guy Deacon Jones came home and said he'd learned for the first time what fear really was.

And Glanville was bowled over so badly he's doing the only thing he could think of in order to try to get back up.

So here he is, a little more than a year later now, at Hawaii, the new defensive coordinator, an assistant coach. Hawaii, in the Western Athletic Conference, where his old NFL assistant June Jones had overseen the greatest single-season turnaround in Division I football history (from 0-12 to 9-4, in 1999).

Yes, there's a reason why Glanville, now 63, is back in the game, 13 years after leaving his last tickets for the King. There's a reason why the colorful, quotable, long-out-of-the-league former pro coach is now in a closet of an assistant's office at a mid-level college job in the middle of the sea.

Sure, it turned out that Hawaii needed him. (It needed somebody. Last season UH ranked in the triple digits, defensively -- dead last against the run and just one spot better than that, No. 116, overall -- those stats helped in part by whippings of 69-3 at Boise State and 70-14 at Fresno State.)

But no, that isn't it. That isn't where this promise comes from. That isn't the mission he's on. That isn't why he feels like his life is different now. It's not why he was specifically looking to coach players who were 19 and 20 years old.

"If they're bringing cheerleaders over, if they're bringing Kid Rock, they'll fly in, do their show at a base and fly out that same day," says Army Capt. Jeff Beierlein, who has done two tours in Iraq, who got to tell Glanville how, as a kid in Cincinnati, he once launched a snowball at a certain opposing coach.

"They aren't out and about like Jerry Glanville was," Beierlein says.

That's why Jerry Glanville is here.

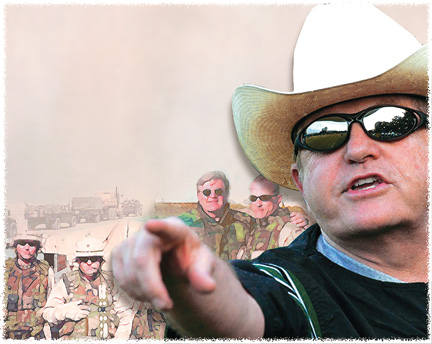

Jerry Glanville, now Hawaii's defensive coordinator, got behind a weapon mounted on a humvee during last year's visit to Iraq.

He saw so many things.

"Every day," he says, stopping. "I don't want to get too emotional. I can't even tell you."

His eyes fill with tears often, these days.

"Every day is different (over there)," he says.

There was the day they were riding in a convoy across the Kuwaiti Desert. The Highway of Death. He's riding with a bunch of kids who had been in college in Minnesota only a few months earlier, Mankato State, Bemidji State. Young guys in the National Guard. The driver's last job was on a Krispy Kreme delivery truck.

"And I needed the extra $600 a month, Coach," the guy says.

And here he is.

Here they are.

Well, giddy-up, Glanville says. Buckle up and go. Here they are. The Highway of Death.

They tell him to come back and coach again. So many he met over there told him that. Of course they did. It makes perfect sense. You'd tell him that, too, if you met him on the street. He's Glanville, the colorful, Elvis-loving, Johnny Cash of a coach who once told an official that, if he kept blowing calls like that, "I'll be bagging groceries."

Bagging groceries!

Who wouldn't want to watch that one more time?

"Come coach us," the driver tells him. They all say it. Come coach us. Come let their generation in on the fun.

Come to Bemidji State.

They grab his insides. They all do, the way they get through this craziness, somehow. The way they handle themselves. Wearing their weapons while playing pingpong (you never, ever, ever let go of your gun -- "there will be no surprise attacks," Glanville says). Staying out extra hours in a war zone because a teammate lost his night-vision goggles and the team wouldn't come in until each one of them had all his gear.

The pictures. "I look at all these faces here," he says. "I can remember talking to each and every one of them." The cook from Kansas City who was the biggest Chiefs fan in the world. The 19-year-old single mom who could put a bullet anywhere you wanted from 300 yards.

"These Navy SEALs," Glanville says, pointing to a picture, "there's 23 of them. They blow something up every night. That's what they do."

There's Glanville sitting in one of Saddam's royal Barcaloungers. There he is with Gen. Custer.

Wait. That can't be right.

It is, of course. That's the man's actual real name. Get this -- he's in charge of intelligence.

Gen. Custer is in charge of intelligence!

"I asked him if his great-grandfather didn't believe the Indians were there," Glanville says.

There's his Humvee gunner, the guy who was in the front vehicle, Glanville perched in the one following close behind, when an Iraqi car pulled between them.

"And (the gunner on the front Humvee) waves him to move over. Only he doesn't wave, he picks up that rifle, cocks it, and puts it right on the guy and the guy pulls over. And he's 20 years old out of New Jersey. Great kid. And I said, 'That was kind of close.'

"He goes, 'Coach ... if you weren't here, he was gone.' "

We've all seen that story gone the other way, on the news. You can imagine the heart pounding, the pulse racing, the blood freezing after a moment like that.

"Well, things like that happen five times a day," Glanville says.

They did. They still do. There is some crazy stuff happening over there. It's a serious and often nasty business, war. Always is. And yet these 19- and 20-year-old Americans, in the midst of all this ...

"It was unbelievable," Glanville says, "because nobody ever griped. Nobody ever complained. Nobody ever asked, 'Why Me?' "

He was assigned a bodyguard with each unit, everywhere he went. Often a fresh-faced college-age kid. All of them said the same thing: "I'll protect you, Coach."

They grabbed him. They changed him. He can see them still, their faces, those eyes. He can still see them, every one.

He has a mission now.

"I didn't want to coach pro football," he says. "I wanted to coach this generation. This is the greatest generation in the history of the world."

These things happen in Iraq.

"He says, 'Coach, will you come meet the people?' I said, 'Where are the people?' "

Well, they're Out There, out where it isn't safe, out where bad things happen every day as a matter of course. They're in the Red Zone. In the war zone. This is where the people live.

This is a definite no-no, of course. The Army wouldn't do it. Are you kidding? Just forget it and move on.

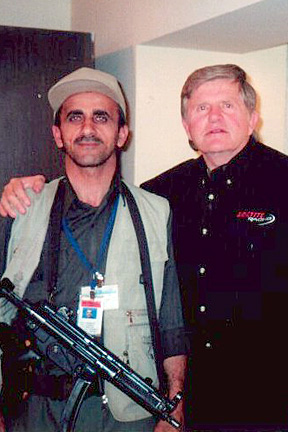

Well, when you're CIA, you know people who know people. "So they got the Kurds," Glanville says. There's a picture of Glanville with his arm around the guy who guarded him when they went out on the town. The best Kurd gunman in Baghdad, they say.

And guess who's coming to dinner. In the Red Zone. At night.

The NFL guys sit down. Good food, nice people. The Iraqis -- or at least the interpreters -- call him "Coach." "Well, at that time they were still looking for weapons of mass destruction," Glanville says. So he can't help it. He's Glanville. He asks.

"And the Kurds looked at me, and said, 'You Americans are all alike. You want to find the weapons.' " And Glanville's glassy eyes seek out his listener's now, to make sure you get it, the way he did, that night. He has to whisper this last part; it's the only way the words can make their way out: " 'Come with me and I'll show you the graves.'

"He says, 'My wife was hung by her breast. My brother has been captured.' He went on and on."

Glanville asks why the Iraqis don't help the Americans find the insurgents.

"And they grab their cloth when they talk about the Republican Guard. They said, 'Coach, the Americans never fought the elite soldiers. The elite soldiers, they did this' " -- grab -- " ' they changed their clothes. One lives next to me over here. Over here is a terrorist from a third country.' And he says, 'If I speak up, I won't be here. This is what I'm surviving. This is how I live.' "

This was the night he decided to coach again. This was when the mission began. The exact moment came after dinner, in the back seat of a car, the getaway race back to camp. They were speeding the wrong way down a one-way in the war zone of the Red Zone running stoplights in the middle of the night. It was one of those God-if-you-get-me-out-of-this promises.

As they sped through the darkness, he said it: If they got back to the Green Zone alive, if he made it all the way home, he was going to coach again. He wanted a team made up of these 19-year-old kids.

SO HE GOT HOME and he made the calls, one after another down the list. It was tough sometimes, the emotion on both ends of the line. One South Carolina mother asked why he could come home and her son was still there. But he was driven now. Changed. This was the promise. No turning back.

So he started looking for a job, a "greatest generation" college job. The Las Vegas Review-Journal quoted him talking himself up for the UNLV gig. He threw his hat in the ring for openings at New Mexico State and San Jose State.

"Seriously," the Houston Chronicle wrote. "We mean it. Now stop giggling."

That seemed to have been the prevailing sentiment. No dice. Few bites. He had not, as we'd all giddily imagined, been bagging groceries all these years. But close. He'd been in television and crashing race cars and giving motivational speeches. Glanville was a fun character. But he hadn't prowled the sideline in more than a decade and all anybody remembered was the wackiness and the insanity and the Elvis and the black.

So there he was at Division II Northern (S.D.) State. This is how serious it was, this mission. A former NFL coach who had regularly spoken with the President of the United States (the first George Bush was a huge Houston Oilers fan) looking for work at a D-II school in South Dakota.

This was how much he just wanted to coach this generation of guys.

Even Northern State had a tough time taking his interest seriously, until somebody finally stopped and took note of the look on his face. And that was that. This was it. How's that for fulfilling a promise? He'd be playing in the same league as Bemidji State.

"I had already told my wife and son that we were going," he says. "They were in what I call 'O.W.,' which is Open Weeping. And the phone rang."

It was Jones. Was Glanville serious about this? Was he crazy? Was he really looking at coming back and taking a college job? In South Dakota?

He was. Correct on all counts.

Well, in that case, Hawaii had an opening. Hawaii was in bad need of some defense. And it would be a chance to ride together again.

"Working for June," Glanville says, "you can't beat that."

He showed up for spring practice in a cowboy hat and shorts, barking directions in his "South Detroit" twang, Bum Phillips for the new millennium. The passion, palpable. The enthusiasm, spreading through particles in the air.

He was back to school like Rodney Dangerfield.

By the third day, the video guy up in the tower had a cowboy hat, too.

"The last time he was on a school campus was 50 years ago," Jones says.

"I was trying to get my transcript changed!" Glanville says.

He revamped Hawaii's defense. He made fellow assistant Mouse Davis, another out-of-retirement former head coach and longtime June Jones guy, watch the video of his worst car-race crash.

"He thinks he's world-class," Davis says. "I think he's crazy-class. He brings in this tape, he shows me. He says, 'Look at this! Look at this!' 'We've got to get sound. We've got to get sound. So you can hear the flames.' "

The players only had him for a few weeks, before spring was over in a blink, and some weren't sure what to make of all this yet. Many of them were 6 years old when the Atlanta Falcons let Glanville go. There are only assorted hazy memories of the crazy, black-clad NFL coach.

Some have seen his act on TV. Others have only been told that he's Jones' old pro football pardner, which was good enough for them.

"Coach (Jones) is putting up some of his accomplishments in the locker room," Hawaii linebacker T.J. Moe says.

But that doesn't matter, does it? They don't need to know who he is. He knows who they are. He knows what they are capable of. He's seen it. He knows it more than they do. He knows what they have inside of them, deep down.

"(They) are part of the greatest brotherhood in the history of the world," Glanville says. "I was with the First Cavalry. The First Cavalry averages 19 years old."

He can see it in them. He can see the desert in them. They've flipped a switch in him. He sees other faces when he looks in their eyes.

His own eyes water often, these days. His voice goes raw. He has to stop and compose himself when the subject comes up. He's a changed man now. This is the mission. This is why he's back, why he's here, an assistant at a college job in the middle of the sea.

He's coaching this generation.

"Because," he says, pausing; whispering now: "They'll do anything you ask them to do."

E-mail to Sports Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]