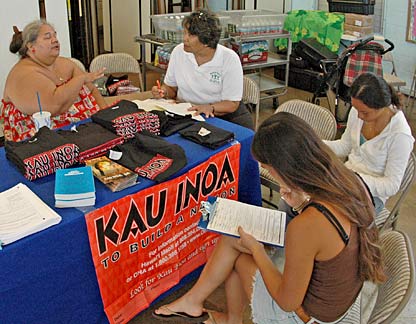

Leona Kalima, left, of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs explains Kau Inoa -- the "place your name" effort -- during a drive in Waimanalo as registrants fill out forms.

Sign-up drives

parallel Akaka Bill

Without hesitation, Cousin Kala Koanui said he registered his name with Kau Inoa, a group seeking to enroll native Hawaiians to vote for or against any new form of self-government.

|

|

Koanui is one of the 21,000 native Hawaiians who, since June 31, have joined the rolls of Kau Inoa ("place your name"), which started taking names on Jan. 17, 2004, on the 111th anniversary of the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Forms must be completed and returned with documentation showing Hawaiian ancestry (Web site: www. oha.org/cat.asp?catid=79).

Kau Inoa proponents say they are a homegrown group of native Hawaiians trying to identify and sign up other native Hawaiians in Hawaii and on the mainland who choose to participate in future decisions regarding self-governance. They stress they are not part of the enrollment of Hawaiians called for in the Native Hawaiian Reorganization Act of 2005, commonly known as the Akaka Bill after its chief sponsor, U.S. Sen. Daniel Akaka.

The Akaka Bill, due for debate on the floor of the U.S. Senate this week, sets up a process for the U.S. government to recognize and relate to a native Hawaiian self-governing entity that is to be formed by the vote of native Hawaiians but will be subject to the "plenary," or absolute, powers of Congress.

Some native Hawaiian groups say the likely process will be for those on the registration roll to vote for delegates to a convention that will draw up models of a new government that will then be voted on by those on the registration roll.

Kau Inoa wants to be the one to create the native Hawaiian roll, rather than the nine-member commission designated under the Akaka Bill.

"Kau Inoa's process takes the register away from the federal government and gives control to Hawaiians. That's the beauty of Kau Inoa's registration. It's Hawaiians taking it away from the federal government," said Charlie Rose, a longtime Hawaiian activist who has been involved in the Kau Inoa registration campaign.

"We want everyone in the kitchen. We need everyone to help cook and put the stew together," said Rose. "We want everyone to sign up and participate."

Rose said he supports the Akaka Bill overall but objects to the bill's designation of a commission to oversee the preparation of what the bill calls "a roll of the adult members of the native Hawaiian community who elect to participate in the reorganization of the native Hawaiian governing entity."

Rose said, "Once the Akaka Bill passes, the secretary of the interior will appoint some political group to conduct the registration. As a Hawaiian, I don't want the U.S. government telling us who is native Hawaiian and how to form our government."

Rose and other Kau Inoa supporters said they hope to sign up enough native Hawaiians for Congress to find their process credible and use it rather than the one defined in the Akaka Bill.

The Akaka Bill's current definition of native Hawaiian is narrower than that of Kau Inoa. It defines native Hawaiian as anyone over 18 years old who is either "a direct lineal descendent of native Hawaiians who lived in Hawaii on Jan. 1, 1893," the year of the overthrow, or someone who was eligible or is a direct lineal descendent of someone who qualified for Hawaiian homelands in 1921.

Clyde Namu'o, administrator for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which hosts the Kau Inoa registration on its Web site, said: "The criteria under Kau Inoa is different from the Akaka Bill. Under Kau Inoa you can sign up as long as you are able to verify you're Hawaiian. It's also not limited to adults over the age of 18."

Kau Inoa grew out of a call in July 2003 from five Hawaiian community leaders -- Winona Rubin of Alu Like Inc.; Nainoa Thompson of Kamehameha Schools; Pualani Kanahele, a kumu hula and professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii at Hilo; Dr. Emmett Aluli, an activist and Molokai physician; and Kaleo Patterson, a pastor and activist -- who held meetings about how to register native Hawaiians to vote for a new government. The group, which now calls itself the Native Hawaiian Coalition, designed the enrollment form and continues to meet to work out a process for creating the new government.

According to the most recent census, 400,000 people nationwide identify themselves as native Hawaiian. It is unclear how many of those people would qualify for either registration.

Critics of the registration drive say that 21,000 names in 19 months of mass mailings and a few months of television ads is a poor turnout, indicating there is little support among native Hawaiians for self-government.

OHA's Namu'o defended the effort, saying Kau Inoa is signing up people at a rate faster than the state signs up new voters.

Namu'o said: "It's challenging. We're not just signing up people here, but across the country. We only started TV ads in Hawaii over the last few months. Before that it was mostly word of mouth."

OHA is advocating enrollment and has financed some of the campaign's mass mailings and advertising. OHA has conducted six mass mailings directed to 75,000 people. Printing costs for those mailings amounted to $40,000, and postage was another $12,000. Other groups, such as Alu Like, have also done mass mailings at their own expense.

Namu'o and others acknowledge that some native Hawaiians are slow to sign up because there is confusion over the intent of the registration, and some are suspicious because OHA is pushing for the sign-up.

Namu'o said some are wary because they think the registration is part of the Akaka Bill and that signing up is supporting it.

Namu'o said: "Some people are suspicious because OHA is a state agency, so there's fear that if they sign up and OHA retains all that private information, the state will get it. No, it won't. But to ensure that, Hawaii Maoli was set up as an extra level of protection."

Hawaii Maoli, a nonprofit organization whose parent is the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, was formed to retain the forms, information and a computer database. Under its nonprofit status, Hawaii Maoli cannot lobby for the Akaka Bill, but its parent can. Hawaii Maoli is intended to hand over the enrollment information to the new governing entity.

Rose, acting director of Hawaii Maoli, said the group receives the application forms, provides verification assistance and "maintains the (computer) database in a safe and secure environment."

The next step will be for Hawaii Maoli to put registrants' names -- without private information such as address or birth date -- on a Web site.

"Hawaiians are always suspicious," said Toni Lee, president of the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, which is lobbying for the Akaka Bill. "How many times do we have to sign up for things?"

Lee said: "My generation is like the silent majority, asking, Should I or shouldn't I sign up? People should sign up. When it comes time to decide anything, if your name is not on the registry, you will not be given a ballot, and you will not have any say."

Lee added, "Signing up is not making a decision. It is just making yourself available to make a decision later."

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]