About the family feud with brother Marvin Fong

|

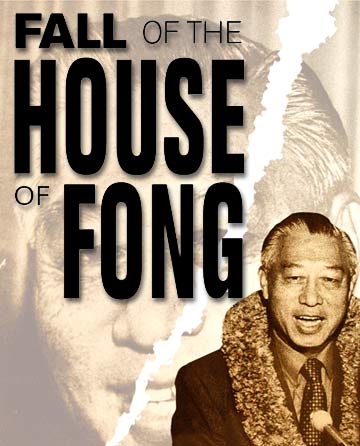

A 1985 letter sheds light

on a scathing feud between

the senator and a son

!n sorting through the personal papers of the late Sen. Hiram Fong Sr., daughter Merie-Ellen Fong Gushi found what she believes are clues to why her twin brother, Marvin, has spent the last eight years waging wars in boardrooms and courtrooms against his parents and three siblings.

A letter dated Dec. 6, 1985, written in Marvin's spidery handwriting, was addressed to his father and began: "I have never in my life hated anyone, but I hate you.

"For 37 years you have degraded me, making me feel I was 'good for nothing.'"

Marvin wrote: "I promise to hurt you as much as you have hurt me in 37 years. ... I will publicly embarras (sic) you; I will destroy whatever is left of your precious name. It may be tomorrow, a year from now or in five years, just expect it in your lifetime. You only care about your name and money. ... I will rejoice in your downfall."

Marvin's battles, played out publicly in at least three major lawsuits, ripped apart the family financial empire, drove his parents to declare bankruptcy as a strategy to protect their remaining wealth and resulted in Marvin and his wife, Sandra Au Fong, gaining ownership of Market City Shopping Center and control of the most valuable remaining family assets.

In a symbolic end to the Fong saga, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court trustee auctioned off the family estate on Alewa Drive for $1.68 million to a developer last week.

In 1950, Hiram Fong Sr., the ambitious son of poor Chinese immigrants who graduated from Harvard Law School and became the first Asian-American elected to the U.S. Senate, built that house high on a ridge overlooking the sea and downtown Honolulu. Fong, a Republican, served from 1959 to 1977.

As a businessman, Sen. Fong made and lost millions. He lived his last weeks on a bed in the living room of that once-elegant house, which, like his fortune, declined into ruin.

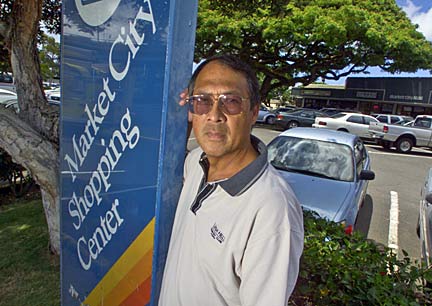

Marvin Fong, one of the late U.S. Sen. Hiram Fong's sons and now president of Market City Shopping Center. A long-standing and bitter family dispute has torn the prominent family apart -- and dissolved most of the late senator's empire.

Hiram Jr., 'anointed son'

"This whole thing with Marvin is like 'King Lear' or something out of the Bible," said Hiram Jr., the oldest son, in a recent interview at the house, which is now crowded with moving boxes.Referring to Marvin's 1985 letter, Hiram Jr. shook his head sadly and said, "He accomplished what he set out to do in the letter."

Junior, as he is nicknamed, is trained as a lawyer and served briefly in the state Legislature and on the City Council before trying his hand at various disastrous business ventures, including a failed floating restaurant and a Laotian gold mine.

As the firstborn in a Chinese family, Junior was the anointed son destined to follow in his father's footsteps.

Today, Junior, 65, who has languished in involuntary bankruptcy since 2001, is living at the family home until the sale is complete. For several years, Junior, who chain-smokes and reads westerns by Louis L'Amour, chauffeured his father every morning to his office at Finance Factors, one of the companies he helped found.

Several afternoons a week, he drove his father to St. Francis Medical Center for dialysis treatments. Junior and his sister Merie-Ellen, known as Muffy, who lives on Maui and works in her husband's landscape business, have been the chief caregivers for their parents. Before Sen. Fong died, he asked the two to take care of their mother, Ellen Lo, who now lives in a care home.

In February, Junior was evicted from the family's dilapidated former Kahaluu vacation home by its new owners, Finance Factors. Junior unsuccessfully represented himself in the eviction proceeding held in Kaneohe District Court against a team of lawyers from Finance Factors.

Asked what he will do when the family home is sold, Junior joked, "I will buy a van to live in and park it in Finance Factors' parking lot."

In an interview, Marvin, 57, said sadly, "My father was never fair to us. He always took Junior's side."

In court documents, Marvin, who was the "baby" of the family, refers to Junior as "the preferred son" who his father bailed out of a series of failed investments, taking on loans until the banks turned him down for more and the foreclosures began.

In documents filed in his father's bankruptcy case, Marvin wrote that his father and Junior began their downward slide in the 1970s when the two co-signed loans "on a disastrous investment in the Oceania floating restaurant" and lost about $1 million. In the same court documents, Marvin said, "Since then, and in part because of that catastrophe, Fong Sr. has willingly and actively participated in Fong Jr.'s downward spiraling mishaps and wrongdoing."

Marvin said his father fought for years to prevent Junior from having to file bankruptcy.

"It was a pride thing, an ego thing. My father had worked his way up, and he felt that the family name was so important that if Junior filed for bankruptcy, it would be a reflection on him," he said.

But in 2001, Junior was forced into involuntary bankruptcy by creditors who had won a legal malpractice case against him and could not collect $1.8 million.

Marvin said: "My father would bail my brother out again and again, and then when my father got into (financial) trouble, he came to the other siblings and asked us to sign onto loans to bail them out."

Marvin, who described his father as someone unaccustomed to being told no, said, "My other siblings couldn't say no to my father, and they lost everything."

"It's a tragic story. My dad worked his way up and lost it all. I told him he could give his money to Junior but don't give him mine," Marvin said.

In his 1985 letter to his then 76-year-old father, Marvin wrote: "You are no longer important. You are just a figurehead at Finance Factors collecting your money and reading the newspaper. You are so busy protecting your reputation that you have lost your character. You are a sinful, prideful, evil man who God has trouble loving."

Former U.S. Sen. Hiram Fong, his wife, Ellen, and then-Gov. Ben Cayetano carry signs as they make a grand entrance into the Hilton Hawaiian Village Coral Ballroom in an event benefiting the Hiram L. Fong Endowment in Arts & Sciences.

Fight over cemetery shares

Last August, Sen. Fong, 97, died at the family home with his daughter at his side. Muffy gave her father $50,000 toward his legal battles with Marvin. At the time of Fong's death, Muffy and her two older brothers, Junior and Rodney, were at such odds with Marvin and his wife that Muffy sent a letter demanding they not attend the funeral.While the three siblings accompanied their mother in her wheelchair to the funeral, Marvin and Sandy bought a newspaper display ad picturing a sunset with text that said they wanted "to thank everyone who has helped us through this difficult time following the death of my father."

Last January, as Muffy, Rodney and others headed into a shareholder fight with Marvin over another family-related company, Ocean View Cemetery Ltd., Muffy sent Marvin's ancient letter with a cover letter of her own to 125 shareholders hoping to sway them on a vote. The Star-Bulletin obtained both letters from a non-family member who is not part of any lawsuit. In addition, the Star-Bulletin obtained a third letter dated Feb. 2, 2005, that was Marvin's response to shareholders.

Muffy declined to comment to the Star-Bulletin.

In her letter to shareholders, Muffy wrote that Marvin's "vendetta against my father is very deep seeded (sic). How he got this way is a mystery. My parents have been very generous to Marvin, treating him to one-quarter of the family's wealth."

As his quarter-share of the family assets, Marvin was given shares in Market City, an entity that until last year owned the Market City Shopping Center on Kapiolani Boulevard as well as the historic Kress building in Hilo and another shopping center in Oregon.

Marvin was also given shares in Finance Enterprises, a group of companies his father founded with five other families in 1952. Marvin was given a one-quarter stake in the 725 acres in Kahaluu where Sen. Fong's Plantation and Garden was built.

Sen. Fong had hoped to immortalize his name with the gardens in which he personally attended to plantings. In 2002 he defaulted on a $1 million loan from Bank of Hawaii, and part of the property went to auction twice. In the end a California developer bought a 50 percent interest in several hundred acres of conservation land. Rodney and his wife, Patsy, with financial backing from Muffy, Junior and others, retained control of the pavilion area, where local weddings are sometimes held.

In an interview, Junior said there was "a huge difference in philosophy" among the children over their inheritance. Junior, Muffy and Rodney all believed it was still their father's to use.

Marvin did not. He said, "The old Orientals think that they give you assets but they can pull them back at any time. It's in your name, but if you are an obedient son, you're supposed" to give them back.

"I guess in China that's how it was. Well, we're in America now where everyone has property rights. We (Marvin and Sandy) had to stand up for our rights because if we didn't, we'd be in the same predicament my siblings are in. They lost everything."

In a 1996 interview with Hawaii Business, Sen. Fong said he made a mistake giving his children money. He said, "As I look back, I should have tied it up in a trust. ... They would only get the life interest or the income, but they cannot touch the principal."

In her letter to shareholders, Muffy wrote that her father "was a very talented and successful man who expected more from his children than we were able to provide. Because he provided so well for us, we never had his determination and, in a way, we all disappointed him."

Muffy wrote, "Marvin's reaction to all of this is not appropriate behavior. No parents should ever have to take the public abuse Marvin showered on my mother and father during their golden years."

In a Feb. 2 letter to the same 125 shareholders, Marvin apologized for his sister's "unfortunate" letter that took "a private matter between my dad and myself into a public arena."

Marvin's l985 letter to his father was written just after Marvin had asked his father for raises for himself and Sandy for managing Market City. The senator turned them down.

In 1946 the Fong, Chun and Chang families bought a 3-acre vegetable patch for $100,000 and built Market City, anchored by Foodland.

In 1983, Sen. Fong stepped down as chairman of Market City and gave day-to-day management control to Marvin and Sandy, who holds a master's in business administration from the University of Hawaii paid for by Market City. Previously, Herman Fong, an uncle, who had a high school education, had run the shopping center for years from the trunk of his Buick.

Marvin's letter said: "Yesterday was the last straw, when you insulted my wife and I, saying that any high school graduate could run this shopping center.

"I will not take any more insults from you. This is war."

Market City became the first major lawsuit and turf war between father and son.

As Marvin and Sandy saw it, they were the ones who took over the center when a major tenant had just left, and over the years they turned it into a profitable business.

In court records Marvin testified that he and Sandy brought the center from a net loss of $36,620 in 1983 when they took over to a net income of $865,934 on revenues of $2.9 million by 2001.

"My father refused to ever give us credit for building up this business," said Marvin, adding: "My father would say this company is to support the widows and children. But that's not how to run a company. You don't form a company just to give money to people who don't work. ... It was a gravy train."

"Instead of helping the company grow by putting the profits back in, they would just pay out huge dividends, and all these nonworking directors would get salaries," Marvin said.

Sen. Fong saw differently. In court documents he said the "success of the company is due all to my efforts. Everything I've done there has been profitable. ... The company didn't just grow because of Market City, it grew because we did a lot of investment outside."

Court sides with Marvin

During the 1990s, as Sen. Fong was under increasing pressure to find money to serve his loans, Sandy and Marvin wanted to protect their ownership stake in Market City and keep the $2 million cash on its books from his reach. The two also wanted permanent control of Market City. Marvin said that there were three distinct groups inside the company, each with the same voting power: Marvin and Sandy, the senator's group and the Chun family.Marvin and Sandy knew, according to court papers, that if they could acquire his parents' 806 shares and those voting rights, they could take control of the company.

In 2001, according to bankruptcy court papers, Marvin and Sandy approached Sen. Fong with a deal to buy the 806 shares for more than $2 million. By May 2001, Marvin and Sandy had gained control of the Market City board. With board approval, they began cutting dividends and gave Marvin a salary increase of 350 percent and Sandy an increase of 680 percent.

But, according to court papers, Sen. Fong reneged on the stock deal.

Marvin said that in a board meeting, his father looked at the deal and said, "I don't remember signing this. I think you committed fraud on me."

Marvin said, "I just felt stabbed in the back."

In court papers, Marvin accused his father of "selective memory loss."

In October 2002, Marvin and Sandy sued his parents in Circuit Court over the 806 shares. Three months later the court ordered the shares sold to Marvin and Sandy.

Sen. Fong filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on March 7, 2003, three days before the court-ordered sale of the stock. He hoped to get relief from his creditors while getting the bankruptcy court to reject the stock sale.

In bankruptcy court documents, Marvin wrote that his father, "at the ancient age of 96, is embroiled in intractable financial trouble caused by himself and through the dereliction's of Hiram Fong Jr."

Sen. Fong's gamble failed when the bankruptcy court ruled in favor of Marvin and Sandy.

Once in control of the voting bloc, the pair were able to force the other shareholders out of the company, and Market City was spun off into two companies. Marvin and Sandy retained Market City and the Oregon shopping center. The minority shareholders got control of the debt-saddled Kress building.

In his Feb. 2 letter to Ocean View shareholders in which he apologized that his sister made his 1985 letter public, Marvin wrote that Muffy "infers that I need help mentally because I sued my parents and Ocean View. I had to sue my parents because they executed an agreement with my wife and I to purchase their shares of Market City and they breached that agreement. That was one of the hardest decisions that I ever had to make."

Marvin's letter to shareholders concluded, "My dad and I had our problems, but I have made peace with him. We have both forgiven each other and moved on."

Marvin told the Star-Bulletin that he had not spoken to his father in about four years, but before Sen. Fong's death, he visited him alone in his room at St. Francis Medical Center. "We made peace. I told him I was a bad son. He said it was his fault."

Junior said that when his father came home from the hospital the last time, "We asked him about whether he had talked to Marvin at the hospital, and he said, no he didn't remember. So, if Marvin had a conversation with him, it was pretty one-sided."

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]