|

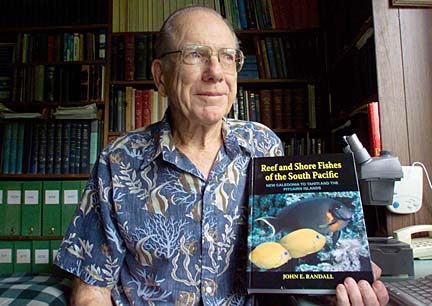

A Bishop Museum researcher swims

back into the spotlight with an in-depth

look at South Pacific fishes

The world's leading authority on tropical marine fishes says his father wanted him to be an architect.

But growing up in Beverly Hills, Calif., John E. "Jack" Randall was intrigued with marine life in tide pools.

He filled an aquarium with plants and animals from tide pools until it leaked and 25 gallons of sea water flowed onto the floor of his father's den. Fishing with his mother off anchored barges and later off live-bait boats fanned the youth's interest in fishes.

"It's just the 'right place, right time' story," says Randall, who specializes in ichthyology, which deals with fishes, their structure, classification and life history.

Randall, who has spent more than 50 years studying and photographing tropical marine fishes in the South Pacific, has described 555 reef fishes, more than anyone in history, written about 10 books and more than 635 publications in marine biology.

His newest book is "Reef and Shore Fishes of the South Pacific, New Caledonia to Tahiti and the Pitcairn Islands," published by the University of Hawaii Press. The 720-page book has more than 2,000 color photographs he took of fishes, mostly underwater, with detailed descriptions. A book signing will be held from 6 to 7 p.m. tomorrow at the Waikiki Aquarium, and Randall will talk at 7 p.m. about mimicry of fishes.

|

He and his wife, Helen, recently attended the Indo-Pacific Fish Conference in Taiwan, where he discussed fish mimicry and received an award for distinguished contributions to Indo-Pacific ichthyology.

The award is named for Pieter Bleeker, the greatest ichthyologist of all time, Randall said.

As for his own stature as the leading authority on tropical marine fishes, he says, "A lot of it is lucky, being early and learning scuba and studying fish, finding many species just because I'm the first guy there."

Curiosity, enthusiasm and boundless energy also had a lot to do with it.

Attending UCLA after discharge from the Army in 1946, Randall dipped his long-john Army underwear in a wash basin of latex rubber cement to create possibly the first wet suit for skin diving and spearfishing in the cold sea.

Then one day at an Army-Navy surplus store, he saw a steel tank wrapped in wire "with an odd contraption at one end, terminating in a mouthpiece."

He was told one could put compressed air in it and go underwater. He bought it for $25, made a type of backpack and mounted the regulator on the right-hand strap at his shoulder.

He describes his experiences in an article in the Atoll Research Bulletin Golden Issue (1951-2001) published by the National Museum of Natural History.

After graduating from UCLA in February 1950, Randall sailed to Hawaii on a 37-foot ketch, Nani, to become a graduate assistant in zoology at the University of Hawaii.

|

In the embryology lab, where he was supposed to demonstrate a chicken's reproductive organs, he found a live rooster and hen running around.

Helen Au, who had just earned a master's degree at Boston University, also was a new lab instructor and prepared the birds for dissection because he did not know how, he said.

He invited her to his sailboat for a dissected chicken dinner that night, he said, and a year later they became married partners and collaborators.

His first academic position was at the University of Miami Marine Laboratory. Then he became a zoology professor and Institute of Marine Biology director at the University of Puerto Rico.

Returning here in 1965, he directed the Oceanic Institute, then had a split position at the UH Institute of Marine Biology and the Bishop Museum.

He left the museum during its economic troubles and returned part time a few years ago under an Engelhard Foundation grant. His daughter, Lori O'Hara, also is a technician there part time.

When he first went to the museum in 1970, Randall recalled, the fish collection was in the carpenter shed jammed in cardboard boxes "that looked like they'd been rained on."

Throughout those years, he traveled to Pacific islands, studying reef fishes and ecology and mapping the marine environment.

In a few glimpses of his adventures, he noted a photo of a scorpion fish, which has "viciously venomous spines." In New Caledonia he was going to take a picture of one that was on ice in a chest, and he reached in and pricked his thumb, he said.

"The pain was just horrendous. I knew the thing to do was to put the injured member in hot water as hot as I could stand it and the pain ebbs away." But as the water cooled, the pain returned, he said.

"I stood 2 1/2 hours running in hot water with my son feeding me rum drinks until I could finally take my thumb out and I could still stand the pain."

Randall worked on many projects over the years, such as the cause of ciguatera fish poisoning, and he has tried to answer questions about fishes, such as why shore species in deeper water take on more red pigment.

Randall and his wife are co-authors of a series called "Indo-Pacific Fishes" published in color at the Bishop Museum. They are now up to 37 monographs, he said, noting his wife is managing editor and "does the real work."

He has written a Hawaiian-fish book that is being reviewed, and he has plans for one on tropical fish of the West Indies, he said.

Randall said he has become increasingly alarmed about the destruction of reefs and the marine environment from human activities and global warming.

"It's grim. It really is," he said. "Coral reefs are going to go." Some fish that feed on algae will survive, but coral polyp feeders and all little fish will disappear, he said.

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]