Sister says she saw

‘Peter Boy’ dead

The claim is hard to prove

because the girl was 4 at the time

» State wary of proving abuse

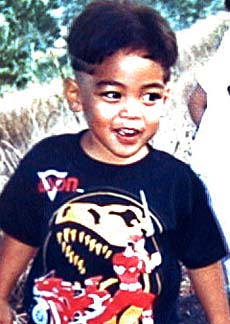

Peter "Peter Boy" Kema Jr.'s younger sister, Devalynn, told a psychologist in June 1998 that she had seen her brother "dead" in both a closet and in the trunk of her father's car, according to one of 2,000 pages of documents publicly released for the first time today by the state Department of Human Services.

Psychologist Steven Choy, who interviewed the girl when she was 5, a year after the alleged events she recounted, wrote that Devalynn said she saw Peter Boy in a box "dead" in her parent's closet and they "took" the box to Honolulu.

Choy also wrote that "she reported that she saw Peter Boy 'dead' in her father's trunk."

|

But the girl's credibility is in question because she later told Choy "Peter Boy is alive in Honolulu."

Choy, explaining the discrepancy in the girl's reports and the potential difficulty for prosecutors, said, "Her understanding of death is very consistent with her age."

Human Services Director Lillian Koller released the documents in the Peter Boy case to get justice for the missing child and to use it as a case study to reform flawed procedures within the department.

Koller was appointed by Gov. Linda Lingle in January 2003, and therefore was not overseeing the department during the investigation of the case.

Many of the documents released this morning, with blacked out names, were family court papers that ranged from social worker and medical records of abuse of Peter Boy and unnamed siblings to psychologists' assessments of his parents, Jaylin and Peter Kema Sr., and even an application for a restraining order filed by Jaylin against her husband, alleging abuse.

Peter Boy, the third of four children in a Big Island family, was about 6 when he was last seen publicly in 1997. Peter Sr. later told police that he handed the boy over to a friend, Aunty Rose Makuakane, when he was in Aala Park during a trip to Honolulu in mid-1997 to look for work on Oahu.

Police found no evidence that the woman existed or that Peter Sr. and Peter Boy took a flight to Honolulu around that time.

At the urging of authorities, the Kemas finally reported Peter Boy missing in January 1998.

With suspicious circumstances around the disappearance, Peter Sr. said at a press conference on April 27, 1998: "I did not kill my son. As far as I know, no, I did not kill him."

A week after Peter Boy was born in May 1991 with respiratory problems, his older half-brother and half-sister were removed from the Kema family because of abuse. An intake report by Child Protective Services on May 8, 1991 rated child abuse in the Kema home as an eight on a scale of zero to eight.

Peter Boy was examined at Hilo Medical Center three months later, on Aug. 11, 1991, with new and old fractures or injuries to his ribs, shoulders, knee and hip, according to a medical report.

The report said the injuries were "caused by twisting of the limbs, which was completely unexplained by either parent." Jaylin had only told doctors the baby was "fussy" the night before.

A Hilo social worker reported that he told the Kemas that after the hospital visit, Peter Boy would be put in foster care.

In 1994, Peter Boy was returned to the family alone and the older children rejoined the family in 1995.

Psychologist Choy said Peter Boy's younger sister, Devalynn, said Peter Sr. forced her brother to eat "doo doo." She said Peter Sr. tied Peter Boy with chains and a rope and then dumped him, naked, into a trash can.

Choy assessed her intelligence at normal to low normal.

Choy wrote that he did not conduct a forensic interview with her, apparently meaning he did not go into details about her reported death of her brother.

While the girl's description of Peter Boy being dead may be subject to interpretation, the two older children gave at least one foster parent chilling descriptions of the abuse he suffered. Their accounts, which are not dated, partially corroborate Devalynn's story.

At one point while driving to school on the Big Island, the children told their foster parent that Peter Boy was locked in the trunk of the car a lot, and at times he would be piled with blankets while locked inside during the peak heat of the day.

The two also told the foster parent about a mosquito bite Peter Boy got that became so infected the children described it as "a big hole in the crook of his arm." They said "it moved, going down to his wrist. It really stank and it had a lot of pus. We are not sure if he ever went to the doctor."

The two told the foster parent that Peter Boy was made to sleep outside, often handcuffed, and with no pillows, cover, or jacket. When allowed to sleep inside, Peter Boy was tied to a bed post with a rope, sleeping on the floor with no pillow or blanket.

The foster parent reported the two children said Peter Boy was always hungry because his parents didn't feed him. And when they did feed him, he was force fed until he vomited. The children said they didn't know why the boy was treated like that.

The foster parent reported the children said Peter Boy "was tied to the bed because he would go into the kitchen and take food because he was always hungry because they hardly fed him."

The children said Peter Sr. once showed all of the children rice with worms in it, then cooked it and made the children eat it.

The children took baths only once a week, and were forced to bathe with cold water from a garden hose.

An unidentified social worker wrote in a May 10, 1991, report to family court that "Jaylin has given no justifiable explanation for the (children's) injuries and she denies that (blacked out name) has been hit by her live-in boyfriend (Peter Sr.)."

The social worker told the court that Jaylin "is in complete denial that her live-in boyfriend may have harmed the (children)" The social worker noted that Jaylin "does not seem able to protect her (children) and the (children) seem at risk of harm if returned to the home."

Some documents suggest Jaylin was fearful of telling anyone about abuse in her home. In a September 1992 memo, a social worker who interviewed Jaylin said, "Without admitting anything, Jaylin asked what would happen should she say that her (now) husband (Peter Sr.) abused (the children)."

The unidentified social worker replied he or she did not know what criminal action, if any, would be taken against the father. The social worker said "Jaylin then asked specifically about jail time."

Social workers and psychologists painted a picture of a couple fundamentally unable to provide a safe home for their children.

A 1991 evaluation of the couple by a clinical psychologist found deep emotional problems in both parents stemming partly from their rough upbringings.

Jaylin told the psychologist that she had been sexually molested around the age of 12 to 13 for an extended period of time. The alleged perpetrator's name is blacked out in the documents.

She claimed to have had subsequent difficulty fitting in at school and was suspended in high school for a fight with another girl in which the other girl suffered a broken jaw and nose.

She also said Peter Sr. had beaten her on several occasions.

Both of Peter Sr.'s parents died by the time he was 10 and he described his upbringing by an uncle and half-sister as neglectful and abusive. His relatives frequently used marijuana and beat him severely, he said.

The psychologist noted both Peter Sr. and Jaylin exhibited "pervasive and long-standing features of marked psychological disturbance" and noted a strong potential for dysfunction and abusive parenting.

An Aug. 19, 1992, memo filled with blacked-out names that transferred the Kema case from one social worker to a new one indicates someone at CPS was concerned.

The memo said the case "looks pretty straightforward on the surface, but this permanent custody will be emotionally difficult for whoever pursues it. These parents are young, and have been able to suck in some of the providers out of sympathy, notably Dr. (Christopher) Barthel. Whoever it is may have to go up against his recommendation, again."

The memo said that "(blacked out names) are at extreme risk if they are placed in the care of either parent."

The memo characterized the parents as "emotional adolescents, focused solely on their own needs, and whining about how unfair the system and life has been to them. In the meantime, their (blacked out names) are hung out to wait. (Blacked out names) were so intimidated they stuttered Uncle Peter's name; the infant (Peter Boy) was fortunate to survive without permanent damage."

The memo also said "The injuries to the infant (Peter Boy) were inflicted over a period of two to four weeks, a fairly clear indication of premeditation, or at the very least, cognition. The injuries to (blacked out) suggest a pattern of abuse rather than a one-time incident, or a disciplinary measure. My concern is that the assigned worker will get caught up in the 'poor me syndrome' of the parents, and lose sight of the real victims here."

Big Island police turned the case over to the county prosecutor's office in 1999.

|

Diana Leone, Sally Apgar, Dan Martin, Helen Altonn and

Gregg K. Kakesako contributed to this report.

Family tree

These are the main family members of "Peter Boy." He was born in 1991, Jaylin Acol Kema and Peter Kema Sr.'s first child together. He has been missing since 1997.

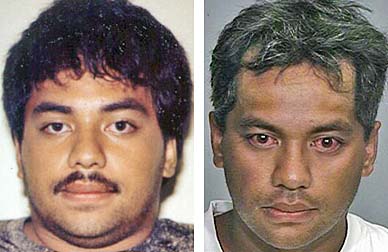

Peter Kema Sr.

Married Jaylin after she broke up with William Collier. Now lives in Hilo area.

|

Jaylin Acol Kema

Mother of Peter Boy. Daughter of James and Yolanda Acol (third of five children). Married Peter Kema Sr., later separated. Lives in Hilo area.

|

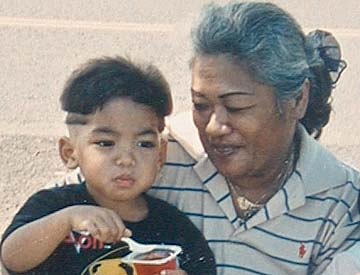

James and Yolanda Acol

Grandparents of Peter Boy. Parents of Jaylin Acol Kema. They live in Kona.

|

Devalynn Kema

Youngest child of Peter Kema Sr. and Jaylin Acol Kema. Her maternal grandparents, James and Yolanda Acol, now have permanent custody.

William Collier

Former boyfriend of Jaylin. They had two children, Chauntelle Acol and Allan Acol. Collier was eventually given permanent custody. They now live in Washington state.

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]