|

Making sense

of sake

A tour of Japan's breweries

enlightens the tastebuds

KYOTO, Japan >> It was in Abaracho, a small sake and wine shop on the main shopping street a few blocks from the Fushimi-Momoyama station, that I had my sake epiphany -- a pure moment when I began to understand the balance of rice and water that separates the best sake from the rest.

The proprietor, Yuichiro Okuda, had poured a tasting set of a ginjo, junmai and daiginjo sakes from local brewers into blue and white "snake eye" cups.

The ginjo Fuhsimi Minato and the junmai Shyotaku were both very good. The Fushimi Minato had a dry, peppery flavor and the Shyotaku a creamy and fruity taste, with a sweet finish.

But the daiginjo, Ichigin, was perfection -- the ideal balance of rice and water, sweet and dry.

The aroma was like a spring day, a light floral bouquet reminiscent of cherry blossoms. The beginning was sweet, but with an slight tartness like apples. The middle became more complex and balanced the tastes of the water, alcohol and rice. The finish lingered for a long time, extending the flavor until it faded like maple leaves on a fall day.

I'm just learning about sake, introduced to the good stuff at the annual "Joy of Sake" tastings each summer at the Japanese Cultural Center.

The more you drink, the more you learn, as you taste and compare so many different quality sakes. And it doesn't hurt that, if you don't spit, it gets better and more enjoyable as the night goes on.

That's the same way I learned to drink wine when I was in my 20s in San Francisco. Friends would come up from Hawaii and I'd take them to wine country. We'd go, not because we were connoisseurs, but because it was a chance to drink free wine. But a funny thing happened. The more wines we tasted, the more we learned.

I started being able to taste the difference between a merlot and a pinot noir. I chatted with the wine guy using words such as "buttery," "oaky" and "fruity." And it wasn't just because if you sounded knowledgeable, they'd reach under the counter for the better stuff.

|

That's why, on a recent business trip, I spent some time in the Kansai region to visit Fushimi, near Kyoto, and Nada, near Kobe, two of the most important sake-brewing regions in Japan.

You can pick up maps of sake breweries -- kura -- at the tourism offices at main train stations. But as of last fall, only Nada had a map in English.

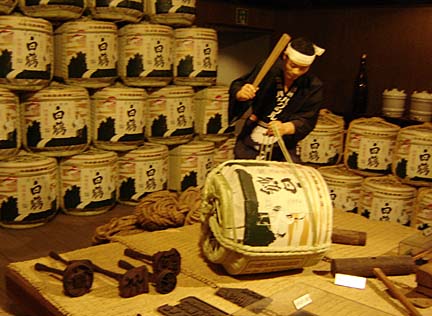

Unlike the pastoral settings of Napa and Sonoma, industrial/warehouse areas are the site of Fushimi and Nada's kura. Many breweries offer tours, but most are in Japanese.

In Fushimi, an older, more traditional neighborhood, it's hard to find English speakers or even street signs in English.

But after a few "doko?" (where) questions and hand signals, I managed to find my way around.

The Gekkikan Okura Sake Museum is probably the biggest and best known brewery in Fushimi. Tour buses pack the parking lot, along with tour guides with flags leading large groups. Even if the tour is in Japanese, English signs explain the history of sake-making in the area and how sake is made.

And you don't really have to know Japanese to find the free tasting room.

A short train ride away is the Nada district of Kobe, Japan's most prolific sake-brewing region. At the tourist information office in the train station, you can pick up an English-language map that features directions to nine breweries within walking distance of each other.

Some are major brewers such as Hakutsuru and Kikumasamune, widely distributed even in the United States.

The larger brewers have museums with English signs and offer scheduled tours. Others are smaller, family-run operations. All offer free tastings. And for a little bit extra, some have tasting rooms serving the better stuff.

As in Napa, the brewers have harvest festivals and release parties. When I visited, the Kobe Shu-shin-kan brewery was celebrating a new sake bottled earlier that day and the 10th anniversary of the rebuilding of the brewery after the Kobe earthquake.

Booths in the courtyard served oden, mochi, red rice, grilled octopus, and, of course, sake.

During the tour, the guide explained that fewer people are drinking sake in Japan while beer sales are rising. But overseas, sake's popularity is growing.

As I sampled the newly bottled sake, a junmai with sweet and grassy overtones, my thoughts wandered to mountain streams and rice drying in fields. In the courtyard, the autumn sun cast long shadows, signaling the end of the day.

I paid for another tasting set, which came with tofu to clear the palate. I took notes, but many labels were in kanji and only available in Japan.

Learning about sake is going to be a daunting task, I thought, but what's life without a challenge? I headed for the train station in search of an izakaya to continue my quest.

Sake basics

>> Sake is a combination of rice, water and koji (yeast). The first phase is to mill or polish the rice. In the best sakes, up to 70 percent of the rice is polished away.>> The rice is washed and soaked in water. The rice absorbs the optimal amount of water, then is steamed and the koji mold added. This is a critical process and varies by sake maker.

>> A yeast starter is added, followed by more rice, koji and water over a period of about four days.

>> The resulting mash is fermented 18 to 32 days, then the mash is pressed and clear sake remains.

>> The sake is then filtered, pasteurized and aged. It's sometimes blended before bottling.

Premium sake types

Daiginjo or junmai daiginjo: At least 50 percent of the rice kernel is milled away.Ginjo or junmai ginjo: At least 40 percent of the kernel is milled away.

Junmai: "Pure rice sake" is made without additives -- and at least 30 percent of the kernel is removed.

Honjozo: A small amount of brewers alcohol is added.

Nigori zake: A cloudy sake that has not been fully pressed.

E-mail to Features Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]