|

Space junk is high-stakes

counting game

Dave Talent knows junk.

That doesn't mean you'll find him at landfills or garage sales.

Talent's specialty is the swarm of orbiting debris that potentially threatens the International Space Station and the shuttle fleet, tentatively due to return to space in late July.

The former Maui scientist spearheads the space-junk program for Oceanit Laboratories Inc., a Honolulu high-tech company with a $50 million Air Force contract to help quantify the risks to satellites and other spacecraft.

Toward that end, the company is preparing to set up two sophisticated, automated observatories at Kwajalein Atoll, 2,400 miles west-southwest of Honolulu.

The sites, part of a planned 15- or 20-telescope network, will allow the Air Force and NASA to fill gaps in their knowledge about the litter that swirls just a few degrees north or south of the equator.

The Air Force's Maui Optical and Supercomputing Site, with facilities atop Haleakala and in Kihei, serves on the front lines of the U.S. effort to track orbital debris and to find hardware that has disappeared over the decades. Complementing radars elsewhere, the Haleakala site specializes in sensitive "electro-optical" observations that detect the sun's reflection on the surface of the shards.

The stakes are enormous as the space agency prepares to resume flights after the Columbia disaster that grounded the orbiters in February 2003 pending a safety review and procedural overhaul.

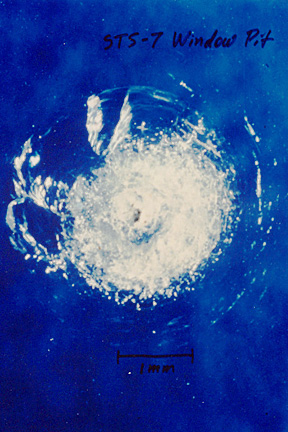

Working with Houston's Johnson Spaceflight Center and Oceanit's Aerospace/Space Surveillance group, based in Kihei, Talent knows that Earth orbit is a dangerous place where even flecks of paint, moving at lightning speed, have punched divots in the windshield of the shuttle.

"A nut or bolt left over in low Earth orbit -- about a centimeter across, the size of a thumbnail -- if it hits a spacecraft, typically at a speed of 10 kilometers per second (22,300 mph), it will carry the energy equivalent to a hand grenade," says Talent, Oceanit senior scientist/astronomer. "That is not a healthy situation."

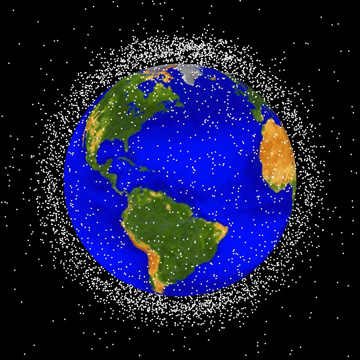

As of last week, from Haleakala and other ground-based observatories, the Air Force was tracking 9,530 objects in orbit, 95 percent of them junk left over from rockets and derelict satellites, Talent said in a telephone interview from Houston.

A tiny piece of space junk caused this pit in the window of the Space Shuttle Challenger during its mission in June 1983. Aboard this flight was Sally Ride, the first U.S. woman into space. The Challenger was lost just after launch in January 1986.

"To date, the station has never been in danger of being hit by a cataloged object, simply because we know where they all are," says Talent, who worked for Boeing Co. on Maui in 1997-2000.

Meanwhile, reinforced panels on the spacecraft protect them from imperceptible grain-of-sand-size projectiles, which pose less of a danger than a nuisance, continually "sandblasting" camera lenses and other surfaces.

The bad news is, those panels do not protect astronauts on spacewalks.

Furthermore, a considerable amount of debris is too small to be tracked but can still do some serious damage in a collision, Talent says.

An object a half-inch to 2 inches across "would still have enough mass to penetrate an area like the space station habitation module," Talent says. And he estimates there are 100,000 objects with a diameter between a half-inch and 4 inches, "none of which are well tracked."

At an altitude of about 220 miles, the space station -- and the shuttle on resupply missions -- flies below the main cloud of debris, which extends from 500 to 740 miles up.

"You're below the worst of it, but you're not quite out of danger," Talent says.

A computer program Talent developed and patented last year helps assess the chances of a satellite, the space station, shuttle or any other orbiting object getting slammed by debris. Known as PODEM, for Phenomenological Orbital Debris Model, the computer model joins others at NASA and the European Space Agency in gauging hazards long recognized but still not precisely quantified.

"Generally speaking, we can expect thousands of objects 1 millimeter and smaller to hit the space station during its operational life, and perhaps five to 10 impacts in the greater-than-1-centimeter range," Talent says. "This is why critical systems have been shielded. For objects larger than about 10 centimeters, we have a catalog of known objects. So, even though such impacts would be deadly, avoidance maneuvers are possible."

He adds: "Am I afraid the space station will get blown out of the sky or something? No, I don't think that is going to happen. Now, the unexpected can always happen, but you don't make strides forward by sticking your head in the sand and not accepting some level of risk."

To further reduce the risk, the Air Force, NASA, Boeing and Oceanit are teaming up on an initiative to find old space hardware that has dropped out of sight, notably 34 defense communications satellites launched between 1966 and 1968. "Though no longer in service, their proximity to geosynchronous orbit makes them a potential hazard for satellites wanting to get to the hottest property in space for telecommunications satellites," the AMOS spring newsletter reports.

Soon joining the search will be Oceanit's Meter-Class Acquisition Telescope, MCAT for short, with a half-size prototype due for installation this year at Kwajalein. During twilight hours, with the sun at its back, MCAT will scan low-inclination orbits. During the middle of the night, it will search the higher, geosynchronous orbits, roughly 22,300 miles up, where satellites can remain over the same spot on the equator.

orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/faqs.html

Oceanit

www.oceanit.com

For students

www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/9-12/features/F_What_Goes_Up_9-12.html

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]