|

Hawaiian registry has

18,000 on its list

An estimated 400,000 Hawaiians

are living worldwide

Bradford Lum is Irish, Dutch, German and Chinese, but it's the three-eighths Hawaiian blood running through his veins that matters most.

That's why Lum and his elderly mother, Lily, entered their names with the Native Hawaiian Registration Program, a database of people with documented proof of their Hawaiian bloodlines.

Many Hawaiians believe a catalog of all living Hawaiians, estimated at 400,000 worldwide, is the key to founding a nation, or at least gaining federal recognition, for Hawaii's native people.

"We need to be a nation within a nation," Lum said, "but we're not even recognized as an indigenous people right now."

Others who entered their names in the registry, including John Kaukali, 67, do not believe a Hawaiian nation or government is a practical goal.

"I really don't think so," said Kaukali, who is half Hawaiian. "You cannot have a nation within a nation."

Kaukali doubts the registry, dubbed Kau Inoa, or "place your name," will do anything to help Hawaiians in his lifetime. He signed up hoping his grandchildren will benefit from any social services the government offers to Hawaiians if they manage to gain the same federal status as other indigenous groups in the United States.

The Native Hawaiian Recognition Act, also called the Akaka Bill, after its sponsor, Democratic Sen. Daniel Akaka, would formally recognize native Hawaiians as an indigenous people in the same way the U.S. government recognizes American Indians and Alaska natives.

Congress is scheduled to take up the bill later this year.

Kau Inoa is the third attempt to count Hawaiians since the 1990s when self-determination for Hawaii's native population became a more prominent issue.

The process became easier after the U.S. Census began counting native Hawaiians for the first time in 2000. Many Hawaiians were inspired by the 1993 centennial of the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani and a congressional apology for the U.S.-backed coup that same year.

The apology resolution included federal recognition of Hawaiians' sovereignty over their lands.

"We have been robbed of our country," Lum said. "I believe it's time to be recognized."

So far, the Kau Inoa project has registered only 18,000 since starting sign-ups in January 2004, according to Hawaii Maoli, the group funded by the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs to gather and store the information.

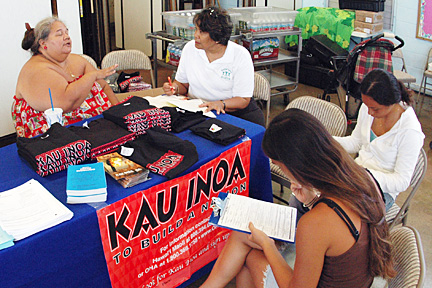

At the Moiliili Community Center this weekend, Corrane Park-Chun waited for registrants at a table covered with sign-up forms and free Kau Inoa souvenir pens.

She collected just nine registration forms after an hour and a half, but said overall sign-ups have risen because of recent publicity generated by large, colorful newspaper ads and TV commercials offering free T-shirts to Hawaiians who "kau inoa."

Each week, Park-Chun, a community outreach specialist for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, canvasses neighborhoods, sets up small booths at neighborhood fairs or larger events such as the Merrie Monarch hula festival in Hilo, and has even visited prisons to persuade Hawaiians to sign up.

"My husband is going to divorce me. I'm never around. I have no life," Park-Chun said.

Many Hawaiians have not entered their names in the Kau Inoa registry, which accepts birth, marriage or death certificates as proof. Some do not want state or federal officials to know they support Hawaiian interests.

"I understand people not wanting to give out their names and addresses," said William Ha'ole, a recent registrant who manages the docent program at Iolani Palace. Queen Liliuokalani, Hawaii's last reigning monarch, lived in the palace under house arrest for eight months spanning 1895-96.

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a state agency, is funding the ads and the sign-up effort, but Administrator Clyde Namuo said the registry is free of state or federal influence because the information is stored in an independent repository.

Almost half of the people with Hawaiian blood live on the U.S. mainland, clustered mainly in West Coast cities, according to the U.S. Census, which included the Hawaiian designation for first time in 2000.

But even those living far from Hawaii are encouraged to sign up. Hawaiians, however, have divergent views on what such a nation or government would be. Many scoff at federal recognition and say the Hawaiian nation is already legitimate.

Others support a Hawaiian government based in the state of Hawaii and sanctioned by the United States. Some demand full sovereignty and the reinstatement of a monarchy.

The most radical endorse a separate nation-state that would partner with the United States only on certain issues, such as defense or trade.

E-mail to City Desk

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]