|

The Guardian

A lifeguard looks back

on 29 years of surf, sand

and saving lives

To many beach lovers, Mark Cunningham is living the life. This year alone he's been featured in singer/surfer Jack Johnson's surf film "A Broke Down Melody"; won the Mexico International Bodysurfing Competition at Puerto Escondido, known as "The Mexican Pipeline"; is co-writing a screenplay about bodysurfers; and is in talks with Quiksilver about various opportunities connected with the surf-wear company.

Most of his opportunities have come about while employed as a Honolulu City & County lifeguard and world-class body surfer who guarded the beach at Ehukai Beach Park for nearly two decades.

But Cunningham retired from 29 years of lifeguard duty on April 1.

"I have a whole other life ahead of me," says Cunningham, a fit 49-year-old at 6-foot-4 and 175 pounds.

It's a little before noon and Cunningham is hanging out at Johnson's house near Ehukai when he spots another buddy, singer Jackson Browne, in the adjoining cottage.

"Hey J.B., we surfing today or not?" Cunningham barks.

"Are there any waves?" the sleepy singer says, looking out at a flat North Shore.

"Couple feet at Lani's; enough to get the kinks out," Cunningham replies.

Browne first learned about Cunningham from Bruce Jenkins book "North Shore Chronicles."

"I had some friends who knew Mark and they introduced me," he said. "He's one of the most honest, real people I've ever met.

"We're very good friends in and out of the water. Mark reintroduced me to Oahu, the real Oahu, because I had been going straight to Kauai. I feel fortunate to know him."

Told later what Browne said, Cunningham blushes, and in an "aw shucks" manner whispers, "That's really nice of him."

Cunningham estimates he's saved "hundreds of people" while "losing about six" during his career, with 18 years spent at Ehukai, home to the Banzai Pipeline, one of the most dangerous surf spots in the world.

"There are a lot of lifeguards who have made a lot of rescues," he says. "Doesn't make any difference how many you save, you never forget the ones you don't."

Retired North Shore lifeguard

The gentle southern breeze blew offshore, exaggerating the sounds of crashing surf. The two watermen's instincts told them that Pipeline was living up to its fearsome reputation.

The pair saw a dozen swell lines of double-overhead waves stacked to the horizon before exploding in shallow water on the coral reef. Then they saw a surfer take a horrendous wipeout.

"I remember moaning, 'Oh God!'" Cunningham says.

Seconds passed before the surfer's board rocketed to the surface through 10 feet of swirling whitewater and "tombstoned." That happens when the surfer's body remains pinned underwater, but his board pops through the surface standing straight up like a grave marker.

"Two more waves passed over and he still didn't come up," Cunningham said. "Don and I stripped to our trunks and bolted for the water."

Cunningham was the first to reach the man but had to use the leash to pull the unconscious surfer to the surface. The first thing he felt was "a limp foot."

"Don and I wrestled the rest of the body to the surface, put him on the board where I tried to do mouth to mouth," Cunningham said. "But there was this awful gurgling sound and my breath was blowing out the side of his neck."

The surfer's throat had been sliced by one of the board's fins. He died on the beach.

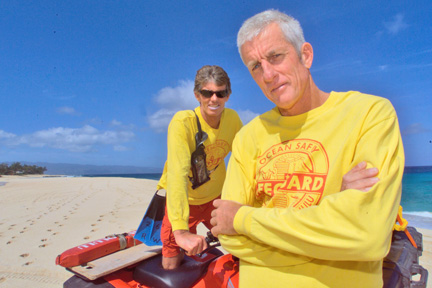

Mark Cunnigham's lifeguard partner at Ehukai was Rick Williams, left. Williams says, "You can count on Mark; he always cared for this beach and any person on it."

"God, I'm so embarrassed wearing a T-shirt with me on it," Cunningham says, quickly removing it.

He grew up in Niu Valley and, like the other neighborhood kids, first learned to board surf. In his early teens he went through "a crazy growth spurt" and became "incredibly gangly, tall, lanky and uncoordinated."

"My board surfing was a comedy routine," he said. "I was swimming more than riding."

But Cunningham also didn't like being "on display."

"On a surfboard it's always like 'Hey look at me,' because you're standing up and I was so tall everyone always could see me," he said.

A lifeguard friend suggested Cunningham get a pair of fins and go to nearby Sandy Beach. After his first session, Cunningham was hooked.

"You're just so close to the wave and usually hidden by it, enveloped in a very personal, one-on-one experience," he says. "There's a sense of being a part of the ocean as opposed to being on top of it. I love touching the curl. It's like a fire hose spraying water against your chest ..."

Cunningham rarely does tricks when he bodysurfs, preferring "to make myself as much a part of the wave as possible, become synchronized."

He also took an early cue from Pipeline surfing master Gerry Lopez to ride waves as far as possible.

"I love long rides," he said. "I get a wave at Pipe and ride up on shore if I can.

"You watch board surfers and they kick out early with their chest in the air. Waves are precious resources and that wave will never be there again, so ride it for all it's worth. Waves are a terrible thing to waste."

IN THE RECENT second annual Puerto Escondido contest against some 30 competitors, Cunningham says "no waves were under four feet." In truth, the waves were so large that on finals day no one but Cunningham entered the water.

"I spanked some of those younger competitors," Cunningham says in a rare display of zeal. "But the surf was awesome. I got the longest rides of my life and I all I needed was Speedos and a pair of fins."

Cunningham is reluctant to talk about his contest dominance but records show that for some 15 years, he never lost when the North Shore was pumping. He was Hawaii's body surfing champion several times, and from 1976 -- the year he became a Hawaii lifeguard -- through the early '90s, he dominated Oahu's best bodysurfing spots: Point Panic, Makapuu, Sandy Beach and Pipeline.

"I really am a one-trick pony," Cunningham says. "I don't have a lot of other skills."

It's not unusual to find Cunningham in the Pipeline lineup competing with dozens of board surfers. While surfers may stay in one takeoff spot, Cunningham is perpetual motion, swimming on his back or breast stroking to a new spot, or even diving underwater to see how the reef is affecting the swell because "position is everything."

"The key element is the takeoff," he says. "Too soon and you may go straight to the bottom and get crushed; too late and you'll get pitched over the falls."

Mark Cunningham still spends lots of time at the ocean, mostly bodysurfing.

"You mean they'll pay me to go to the beach?" Cunningham jokes. "I get to be outdoors and play in the ocean? Oh, I think I'll take that job."

But he worried about becoming a career lifeguard. A Punahou graduate, Cunningham had grown up believing he was supposed to become "a banker, attorney or politician wearing an inside-out aloha shirt down on Bishop Street." He obtained a real estate license but lasted less than a month working in an office.

"I was terrible and never sold an ounce of anything," Cunningham says. "I knew what I was supposed to be doing."

That decision contributed to several personal problems. He realized that he probably couldn't afford to buy a home here and he and his wife, whom he's been separated from for about a year, never had children.

"I'm not regretful about what I've done, but about some of the things I haven't done," he says. "The separation has been very difficult for me. I didn't see it coming, though I'm sure there were signs I ignored."

Did he spend too much time thinking about saving others and playing in the ocean?

"Probably; I let a lot of things out there get in the way of what's in here," he says touching his heart. "You know, I think I would have been a good dad."

For a moment, Cunningham's hawk-like eyes get misty, then he changes the subject.

"My passion for the ocean went hand in hand with my job," he said. "I'm lucky. Like Buffett says -- it's not bad to love your work."

CUNNINGHAM SPENT some of his time living within walking distance of his Ehukai lifeguard tower.

"I was part of the community there," he says. "I saw kids grow up, learn to surf, check out the surf, graduate from high school, get married and divorced.

"A lifeguard gets to be a sort of gatekeeper, guardian, an overseer. It was the perfect fit for me."

"Mark, day in and day out was a total professional," said Rick Williams, Cunningham's longtime lifeguard partner at Ehukai.

Like his fellow lifeguards, Cunningham knew how to spot potential rescue victims.

"Very pale, out of shape, and wearing their fins across the sand," Cunningham says. Williams says Cunningham was "one of the best" at talking people out of going into dangerous ocean conditions.

"He would just chat and point out all the dangers out and make them think they decided to stay on shore," Williams said.

Cunningham calls it reverse psychology.

"I may say I don't know how good a swimmer you are but the conditions look really dangerous for me and I live and work here, and I really don't want to get hurt going after you," he said. "Or I'll ask them if they've noticed that no one, even surfers, is in the water today. Why do you think that is?"

But when people still go in -- like some U.S. soldiers at Waimea Bay a few years ago -- and Cunningham had to make it through a pounding 6-foot shorebreak to rescue them, he's not above delivering a stern lecture.

"Why didn't you listen to me!" he told one soldier. "Now we're both going to get pounded getting in."

He's also heard his share of excuses from rescuees: cramps, not seeing warning signs, or not hearing lifeguards bellow warnings over bullhorns.

"Visitors who don't live by an ocean seem to have tunnel vision," Cunningham said. "It's a nice sunny day, it's warm, and they look at the shoreline and the water looks blue and inviting.

"They don't bother to look way offshore where waves are huge and no one is out."

EVEN CUNNINGHAM has had his share of close calls. He vividly recalls one day in 1986 when he got caught in the "Death Trench," a shallow sandbar area north of Pipeline.

"I just wanted a short swim," said Cunningham, who brought his rescue tube with him. "I hopped into the rip to see if I could make it past the shorebreak and I couldn't."

Currents and whitewater from Pipeline and Pupukea beach areas converged on him in a brown, frothy swirling soup. While floundering over the sandbar, a "huge" set of waves approached.

"I couldn't swim in or out so all I could do was take a deep breath and dive as deep as I could and get rolled," he said.

A trio of triple overhead waves swept over him, each one pinning him to the sandbar.

"I knew I had to get air so I had to climb the line of the rescue tube to the surface," Cunningham said. "When I popped through, another wave nailed me."

That was followed by more waves each one holding him underwater, until he washed ashore.

"I thought I was going to die; I'd never been so scared," he said. "You need those experiences to humble you. It makes you take a step back and fully realize you're not in control out here."

During a recent visit to Ehukai, Williams and other lifeguards greeted Cunningham like a member of the team.

"He's the best," Williams says. "You can count on Mark; he always cared for this beach and any person on it."

"Ninety-five percent of success is showing up," Cunningham says. "I went to work; I did my job."

Cunningham is standing on the empty beach in front of his house, staring at waves breaking over a shallow reef. Cunningham sees bodysurfing potential where others would see lots of nasty coral cuts.

"The beauty of the North Shore is overwhelming to me, so real, so honest," he says. "I feel whole, in tune here. I think that's OK."

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]