Enter the world of

hard-core anime fans

With several hundred anime and manga fans converging on the Ala Moana Hotel on Friday for three days of Kawaii Kon, the first anime convention to be held in Hawaii, now's a good time to take a closer look at the types of dedicated fans who are likely to attend such an event. (Aside from "Drawn & Quartered" anime columnists, of course.)

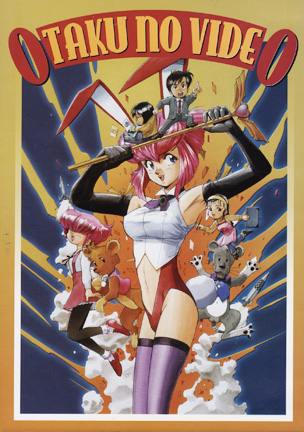

Which means it's a perfect time to look at the 1991 Gainax OAV (original animation video, or direct-to-video animation) "Otaku no Video," a blend of animated comedy and live-action "mockumentary" that alternately skewers and pays homage to the subculture of Japanese fandom circles.

Gainax staff members have openly admitted that the two-part series, consisting of "1982 Otaku no Video" and "1985 More Otaku no Video," is a thinly veiled history of the studio, showing how far some people's love of anime and manga can carry them.

While the Japanese term for describing these fans, "otaku," has since been adopted by Americans to describe anyone who's an anime or manga aficionado, the Japanese use it to describe obsessive fans of any hobby, sometimes to unhealthy extremes. Thus, the word carries more negative connotations in its native culture than it does here.

To be fair, the series does show some of the more unsavory characteristics of otaku. But what it concludes is that while they can be obsessive about their fandoms at times -- perhaps even to the point of borderline insanity -- they enjoy what they do, and they shouldn't automatically be hated for it.

THE ANIMATED story follows Kubo, a freshman in college and a member of the tennis club, and his evolution -- or perhaps, depending on one's perspective, devolution -- into a hard-core fanboy. A pair of chance meetings with his friend from high school, Tanaka, sparks that change.

It starts when members of Tanaka's club get on the same elevator as Kubo, who's going home after an outing with friends at a nearby bar. The group's conversation about Gundam characters, custom-made Captain Herlock stickers and cosplayers (people who dress up in costume as their favorite characters) at a recent convention makes Kubo uneasy, and the revelation that Tanaka is part of the madness freaks him out even more.

A subsequent meeting at a college festival -- where Kubo, taking a break from his club's yakisoba booth, runs into Tanaka and his group, who's cosplaying and selling the latest edition of their fan comics -- doesn't help matters much, either.

Yet there's something that piques Kubo's curiosity about Tanaka's group. He's looking to get out of the tennis club, after all, because he can't seem to get excited about it anymore. So he visits Tanaka's apartment -- a veritable otaku paradise, with piles of videotapes and manga crammed on bookshelves, posters on the walls and materials for drawing fan comics strewn all over the place. Tanaka, in turn, whisks Kubo off to his club's apartment headquarters, with even more videotapes, manga, posters and drawing materials all over the place, plus costumes, plastic models and toys on top of that. If ever there was a place where an otaku would want to die, this would be the place.

Each of the members shares with Kubo their areas of expertise, from breaking down the special effects in certain anime series to the nuts and bolts of replica firearms design. Kubo finds himself enamored with the club's dedication and enthusiasm.

The words spoken by one member, "If you stay here once, you'll never get out," soon prove prophetic, as he starts joining their activities and neglecting his girlfriend.

And once he finds out over the phone that his girlfriend has unceremoniously dumped him because he's drifted a little too far from reality, his future becomes clear: He, along with Tanaka, will devote their lives to become "Otakings," spreading the word of the legitimacy of otaku through merchandising and other means.

IT'S OBVIOUS by the number of anime industry inside jokes that this production was made for fans by fans. Truth be told, many of the visual jokes will be lost on the average viewer. Even the people who wrote the extensive liner notes explaining joke references for Animeigo's domestic DVD release of the series admitted that they can't figure out the meanings of some jokes.

Equally entertaining to watch -- and much less loaded with cultural references -- are 10 live-action segments interspersed throughout the animated story. In these segments, Japanese fans are treated as if they're enrolled in a witness protection program, or perhaps Otaku Anonymous, with digitally blurred faces, altered voices and pseudonyms to protect their identities.

These segments do for otaku what the documentaries "Trekkies" and "Starwoids" did for Star Trek and Star Wars fans, respectively -- that is, they show just how obsessed and insulated from society some of these fans can become. In the first interview, for example, when the interviewer asks a man who's been talking nonstop about his club's activities if he had any real friends, there's a long, uncomfortable silence before he responds, "How dare you ask me that?"

Some of the people interviewed are downright freaky -- the guy who records shows off TV just for the sake of having the "perfect" collection but never watches anything he records, for instance, or the fan of dating-simulation games who doesn't go outside much, has never had a real girlfriend and gets excited over a 2-D computerized drawing.

While some casual anime fans might wince over how these fans are depicted, most will smile and nod and see a small portion of themselves reflected in these people.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]