‘Killing’ a definitive

account of murder

The passage of time often provides objective researchers with new information and fresh insights even when it comes to such extensively covered topics as the Massie-Kahahawai murder case that stunned Hawaii and horrified the nation in 1932.

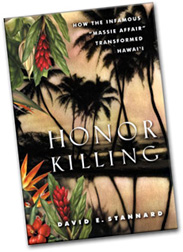

"Honor Killing"By David StannardViking, hardcover, $25.95

|

"Honor Killing" now stands as the definitive account of Massie-Kahahawai. It seems certain to remain so for years to come, unless some overlooked information awaits discovery amid the raw data collected for the long-suppressed Pinkerton Report -- an exhaustive investigation by the national detective agency, commissioned by the territorial government -- or if similar material is buried elsewhere.

The details of both cases are well known: Thalia Massie had an argument with her husband and left a party alone. She returned home several hours later saying she had been beaten and raped by a gang of Hawaiian men. Five men -- two native Hawaiians, one Chinese Hawaiian and two Japanese Americans -- had been involved in a beef with a native Hawaiian woman in another part of town that night. They were arrested and charged with raping Massie.

The evidence presented at trial was sufficient to convince any reasonable person that the five men could not have raped her. There was no evidence of rape. But the trial ended with a hung jury.

A second trial was scheduled. A gang of Navy men allegedly kidnapped and beat one of the defendants, but they did not kill him. Meanwhile, Massie's mother, Grace Bell Fortescue; husband, Thomas Massie; and two sailors were accused and then convicted of kidnapping and killing Kahahawai. The manslaughter conviction led to protests across the nation. Gov. Lawrence Judd gave in to intense political and economic pressure and commuted the convicted killers' sentences to one hour in custody. The four then ducked subpoenas and left Hawaii before the surviving rape defendants could be retried.

Fortescue had conspired with her son-in-law, Navy Lt. Thomas Massie, to kidnap Kahahawai; they were apprehended with his body in the back of their car. Walter F. Dillingham used his political and economic clout to subvert the judicial process during both trials; he also ensured that the conclusions of the Pinkerton report -- that determined no rape took place -- would not be made public.

Adm. Yates Sterling, the commander of U.S. naval forces in Hawaii, encouraged military personnel to take the law into their own hands; he also did everything in his power to convince the federal government and the American public at large that Hawaii was on the verge of a race war and that the islands were so unsafe for white women that more than 40 had been raped the year prior to Massie's allegation -- outright lies.

STANNARD ILLUMINATES the racist attitudes of the era in all their ugliness but also devotes ample space to crediting other Caucasians who put their careers and economic survival on the line to ensure that the five alleged rapists would receive a fair trail and competent legal representation, and that Kahahawai's killers were prosecuted.

Conservatives who know Stannard only by reputation will find that "Honor Killing" is no exercise in haole-bashing. Rather than taking cheap shots in describing the racists and the self-important members of the leisure class, Stannard allows the reader to judge them on the basis of their own court testimony, public statements, personal letters and memoirs. They damn themselves.

Where Stannard brings a fresh perspective to Massie-Kahahawai is in exploring the personal lives of the central characters and why they and others saw themselves as being above local laws. He also shows where Massie-Kahahawai fits in the broader context of tense race relations across America in the 1930s.

Stannard takes the story a step further, stating that the outcome of Massie-Kahahawai caused native Hawaiians to reassess their relationship with the white minority oligarchy, and that the case also caused Hawaiians, Portuguese and Asians to think of themselves as "locals" rather than as members of rival ethnic groups that had been segregated since plantation days.

Massie-Kahahawai was thus the catalyst of the Democratic Revolution of 1954, which peacefully and legally ended 60 years of white rule.

STANNARD ALSO SUGGESTS that as a result of the social, political and economic changes since statehood, Asians can no longer automatically be considered "locals."

Some readers might choose to take offense at the latter observation, even though Stannard makes a case for it. Historians might ask for concrete evidence that the concept of being "local" can be directly tied to Massie-Kahahawai rather than to the work of ILWU organizers here; the experiences of Japanese Americans and military personnel of other ethnicities during World War II; the inevitable increase in the number of Asian-American voters in the territory as the population of American-born residents grew; and the impact of the GI Bill in giving the sons of plantation field hands unlimited educational opportunities.

However, when it comes to providing a detailed, objective and thoroughly readable account of Massie-Kahahawai, Stannard succeeds on all counts. Anyone interested in 20th-century Hawaiian history will find "Honor Killing" well worth reading and a valuable addition to the home library.

Hard questions still hover around the Thalia Massie Case. Shown from left are Grace Bell Fortescue and Thalia and Thomas Massie.

Massie tale still

a juicy one

What is it about the notorious Thalia Massie case that still echoes today?

"American Experience: The Massie Affair":Airs at 9 p.m. tomorrow on PBS Hawaii

|

The Massie posse were found guilty of the murder, but -- under economic pressure from the Navy and rather racist scrutiny from the American mainland, Hawaii's governor commuted the sentence.

These people basically got away with murder, and one that was clearly racially motivated. Today it would be called a hate crime.

It's awful but it's also juicy. And it's loaded with colorful characters, some of whom, like mother Grace Bell Fortescue, are simply monsters. There have been dozens of books written on the subject, or inspired novelizations on it. It's a scab that never heals.

The question is, Should we allow it to? Are we a better society for reliving the Massie injustice, or has our legal system improved because of the case? We'd like to think that justice is colorblind today, but try telling that to an unfairly convicted black man -- or to defense consultants who load the bench with black jurors. The best we can say is that it's better but will likely never be perfect.

The events also took place during the period between wars, a time when racism, buttressed by phony "science," became institutionalized. There was likely no more overtly racist period in American history.

How far have we come? Back then you wore your racism on your sleeve when you ran for office; today it's illegal. That doesn't mean it's gone away.

THE PBS documentary on the subject uses as its primary sources Cobey Black's "Hawaii Scandal" and David Stannard's "Honor Killing," both of which are must-reads for those interested in the case. But the two writers approach the same material with widely divergent points of view.

Black treats it as a worst-case scenario with colorful, bizarre individuals -- an aberration! -- while Stannard places it within the context of Hawaiian social and political history. He believes the tale is emblematic of the crushing effect American society has had on Hawaii, and makes a solid case.

For Stannard what happened to Thalia Massie's "attackers" was inevitable; for Black it's simply bad luck. Wrong place, wrong time.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]