|

‘We’re still here’

Three artists talk about

the triumphs and travails

of a lifetime of art-making

The quintessential artist who never sold a painting in his life, Vincent van Gogh casts a long shadow over every gathering of artists who band together to grumble. Today is no exception.

It's a long way from Arles in the south of France, but in some ways the tableau of artists sitting in a cafe on a sunny afternoon is the same in all times and places. The ordinary man assumes they do little but dabble in paints, space out, sit in cafes and exclaim.

"Work: Leitner / Ojile / Venters"Where: Gallery Iolani, Windward Community College, 45-720 Keaahala RoadWhen: On view through May 7; artists' reception will take place 4 to 7 p.m. Friday Call: 236-9155

|

"It's the Junior League," snorts Timothy P. Ojile, who has called on fellow artists Alan Leitner and Roy Venters to discuss the show they've opened at the Iolani Gallery.

Given the enduring stereotype of the "starving artist," it might seem strange that the latest trend to rock these artists' boat should be calls from every fund-raising group in town, asking for donations of artwork for their silent auction.

The latest such phone call has the excitable Leitner at the edge of his seat. "If you gave art to every fund-raiser that solicited you, you'd be giving away 10 or 12 paintings a year," he says. "Now, I may be way off base, but my feeling is that people who are doing this soliciting are going, 'Big deal, every artist has stuff laying around.'"

Venters says: "Organizations have decided it is chic if you are included in their fund-raiser. They think they are 'making' you, when the reality is that you are making them."

Venters should know. As the unofficial "mayor of Chinatown," he has hung on to his gallery on Nuuanu Street -- living in the cavelike apartment below -- through evictions and unpaid electric bills, watching similar aspirations rise and wither, for more than a decade. Artists might seed the renaissance of a rundown neighborhood, he says, but when the much-ballyhooed Downtown Cultural District finally started bringing money into the area, he watched it go directly to pay the salaries of nonprofit directors.

"This has become a state run by funded organizations," concludes Venters, whose sibylline, dressed-in-black grace -- a cross between the Batman's Joker and the Cheshire Cat -- belies his role as loose cannon in the group. "When the Ford Foundation gives money, why does it have to go to someone's salary? Put the money in the hands of the artists!"

As for silent auctions, "Why don't they ask doctors and lawyers?" he scoffs. "How about an hour's consultation from some big law firm -- isn't that a great silent-auction item?"

Roy Venters shows some of the artwork and artifacts displayed in his Nuuanu Avenue gallery.

"This is what I'm going to do. You can't kill me," he shrugs.

Leitner jumps in, having been accused himself recently of becoming "apathetic" since his 20s, when he and his wife ran a multimedia art studio in Kakaako called the Foundry.

"When you're in your 20s, you're filled with all this idealism because you don't know the realities," says the bearded, bespectacled painting instructor, an unlikely vessel for such gesticulating passion.

"How much have you suffered? How many times has your electricity been turned off? How many times have you relied on people giving you free coupons to get a Jack-in-the-Box burger for dinner? How many times have you slept on the floor?

"But by the time you're 50 years old, you have had the roaches and rats crawl on you. And you know what? I still say I wouldn't give up one of those roaches in my life -- I treasure all of that stuff. But what happens is the idealism turns into reality."

Leitner, too, should know. Today he is a tenured art professor at Leeward Community College, but 30 years ago his workshop hummed with the work of dedicated young sculptors, glass-blowers, and painters such as Doug Young, Ojile and Venters.

"Apathetic" is not exactly the word a casual observer would use to describe Leitner, especially when it comes to the heroism of his fellow survivors.

"These two guys," he says of Venters and Ojile, "they have continued to do art for 25, 30 years. They've survived and they deserve respect.

"A successful artist is a working artist," he declares. "It has nothing to do with what collections they're in or how much money they have. After 20 or 30 or 40 years, if you're still working, you're a successful artist.

"There used to be a time when guys like Tim and Roy were held in high esteem by society and the art world," Leitner says. "And then there's this period of time when there's the 'go get a real job' mentality, which just makes me sick! Because people don't really understand how hard it is to be committed, to give your life to art."

Yet, interjects Ojile -- thoughtful and sensitive today behind his trademark Orphan Annie glasses -- "in Hawaii they are so willing to put you on a pedestal; they want to put you on a pedestal. But it gets awful hard and lonely up there, like you have to constantly reorganize your life to maintain these accolades. I just want to do my artwork and be able to function."

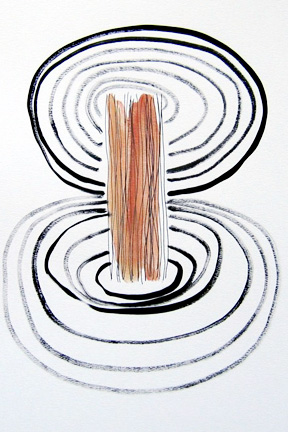

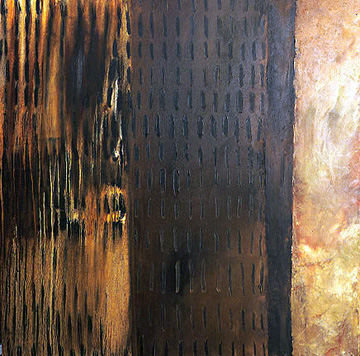

Alan Leitner's "State of Transition" from 2005 is oil, wax and alkyd on canvas.

The public loves van Gogh, observes Venters, because he had such a pathetic life: He cut off his ear, he never sold a painting. Now his works sell for $5 million apiece.

"I believe it's a real con game -- and I have always loved the analogy of being a con artist," he smiles. "What's the difference between a van Gogh painting and something that you found at a garage sale, by me? It's like we ultimately try to convince people that, you know, 'Don't you think this is really cool, don't you think this is valid?' You've got to convince somebody that gluing a bunch of crap together is knowledge."

The exorbitant price of some artwork -- the kind that rewards the very few -- comes down to marketing, he shrugs, because "the rich really want to own something that the poor can't have."

"But where does that leave us, as artists?" Ojile says. "It's one more thing where you're thinking, 'It's weird, it's not really art.' I think I'm willing to say, 'I don't know what art is.' You just do your work."

On this point they all agree, however different their approaches to subject matter and economic survival these 30-some years.

"Something must happen to artists when they get to our age," observes Leitner, "where your art -- just the art part -- becomes really important again. It's almost like a full-circle thing, like you've gone through so much, and getting to where you are, the art part is almost like when you first started: You're just thinking about the art."

"That's because being creative is very personal," says Ojile, who still spends his days painting in the living room of his cramped Makiki condo. "You have this inner dialogue going on, and it goes on for years. It doesn't stop. This is the primary concern of artists, don't you think?"

Which brings us to the story not often told about van Gogh, the one the artists focus on.

"He was appreciated in his lifetime," says Leitner. "He was what was known as a painter's painter: All the artists wanted to see what he was doing, and he was influencing them enormously.

"So in a way that's pretty cool, too, isn't it, to be supported by your peers?" he says, brightening. "It's almost better."

It hardly needs saying that for these three artists, supporting each other has been a kind of sustenance through all the rest.

They don't even remember how they met. But their show will be, on three different registers, a kind of tribute to their survival.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]